Anterior Neck Hematoma (ANH) is a potentially life-threatening emergency due to airway obstruction that can occur at any time following a surgical intervention of the neck. Complete airway obstruction of an ANH can be rapid and without warning, with non-linear and unpredictable progression. Anesthesia professionals must be prepared to diagnose ANH and intervene when a surgeon is not immediately available. Patient safety may require anesthesia clinicians to train to perform surgical interventions in the emergent setting which generally fall outside of the skill sets of anesthesia professionals.

Introduction

An Anterior Neck Hematoma (ANH) can quickly progress to an airway obstruction that can occur at any time following a surgical intervention of the neck. Typically, most patients present within 24 hours of their original procedure.1 Patients with an ANH need swift interventions to mitigate any life-threatening emergencies. We illustrate this important surgical complication and its associated challenges with a specific case of ANH.

Case Study

A 49-year-old man underwent a total thyroidectomy for the diagnosis of thyroid cancer. His past medical history included transient ischemic attacks, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma. He was a current heavy smoker whose preoperative medications included aspirin (81 mg) and an albuterol inhaler, which he took as needed. His labs were all within normal limits. After an uneventful surgery, the patient was discharged from the postanesthesia care unit after five hours of observation and transferred to a surgical ward. The following day he complained of neck swelling, associated with pain, dysphagia, and odynophagia. He denied voice changes and difficulty breathing.

On initial exam he appeared in no acute distress, exhibited no drooling or stridor, and was alert and oriented. His vitals were 98% on room air, blood pressure 167/97, heart rate 70, respiratory rate 18, T 37.2°C, Weight 123 kg, body mass index 36. After removing the dressing, a fluctuant swelling of the anterior neck compartment measuring approximately 8 cm in diameter was appreciated. Physical exam demonstrated limited mouth opening when compared to pre-operative examination due to pain, a large tongue, and Mallampati Class 4 airway.

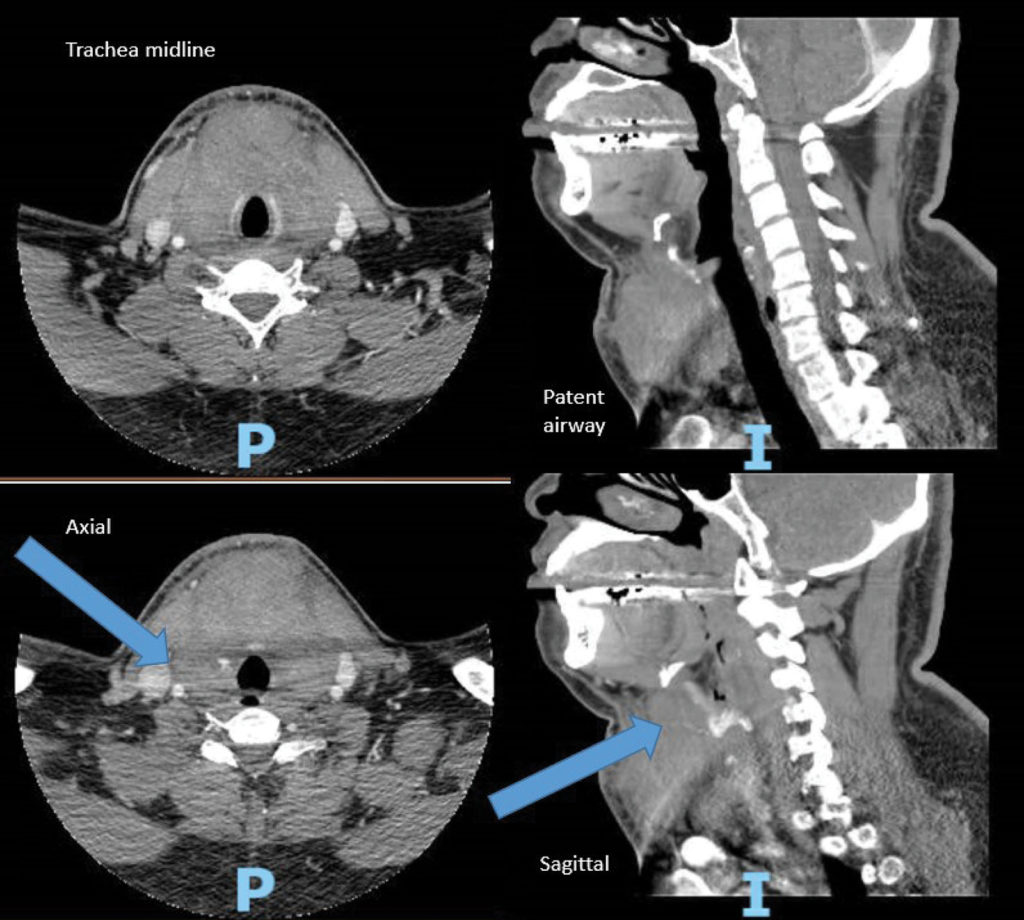

Based on these findings the difficult airway equipment cart was brought to the bedside. An urgent anesthesia consult was called and the patient was taken to the radiology department for a computerized tomography angiography of the neck to evaluate for a potential source of bleeding. The imaging revealed significant anterior neck swelling, trachea midline, patent airway, and active contrast extravasation to the right of cricoid cartilage (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Arrows indicate active contrast extravasation from superior thyroid artery to the right of cricoid cartilage with hematoma formation anterior to the trachea. (P and I are not relevant to this illustration.)

The decision was made for immediate transport to the operating room (OR) to secure the airway. Topicalization of the airway was performed with lidocaine 4% administered via a nebulizer for five minutes. Shortly after administration, the patient became anxious, agitated, and less cooperative. Several attempts were made at oral fiberoptic intubation but were unsuccessful secondary to friable edematous mucosa and bleeding interfering with visualization.

After phone consultation with the trauma surgeon, the sutures were opened along the wound by the anesthesia professional and general anesthesia was induced with propofol. An I-gel laryngeal mask airway was inserted to provide immediate ventilation. The platysma closure was opened using blunt dissection, as instructed by the surgeon, exposing the trachea. Hematoma and clots were partially extruded. An endotracheal tube (ETT) 6.0 was advanced through the LMA into the trachea and correct placement was confirmed initially by direct palpation of the trachea and presence of end tidal CO2. The patient remained hemodynamically stable throughout. The trauma surgeon arrived after intubation and evacuated the remaining hematoma. The patient remained intubated postoperatively for concern of airway edema and was successfully extubated the following day.

Discussion

An anesthesia professional can encounter patients with ANH in many different clinical settings including the postanesthesia care unit, operating room, intensive care unit, emergency department, or on a hospital ward. The true incidence of ANH is hard to estimate, as these cases are likely under-reported in the current literature.2 Closed-claims data obtained from medical malpractice insurance carriers is informative, but represents only a fraction of all clinically significant cases. Proposed factors contributing to ANH may be associated with the procedure, patient’s characteristics, or underlying conditions (Table 1).

Table 1: Procedure-Specific Risk Factors.

| Procedure-Specific Risk Factors |

Anterior Discectomy10

|

| Thyroidectomy/ Parathyroidectomy11-15*

|

Carotid Endarterectomy16

|

Neck Dissection (radical or partial)

|

Central Line Placement18,19

|

| Nerve blocks20 |

| Patient-Associated Risk Factors2 |

|

| *Data regarding the prevalence of bilateral/total thyroidectomy vs. unilateral/partial is still inconsistent; however, the presence of radiation therapy and extent of resection, as well as the degree of dissection, has been implicated. |

Pathophysiology

When considering the potential source of bleeding, one should keep in mind that venous bleeding is often more complex in distribution and more difficult to isolate the site of origin. Arterial bleeds conversely are more obvious and amenable to different interventions, including embolization. A recent case series and review points out that arterial bleeding from the superior thyroid artery can present up to 16 days postoperatively.3,4

Contrary to common belief, the pathophysiology of ANH leading to airway compromise and difficulty in securing the airway is only partially related to the direct effect of the hematoma compression resulting in tracheal deviation, pharyngeal airway obstruction, or posterior tracheal compression where bony support is lacking.

A major cause of airway compromise is hematoma-induced interference with venous and lymphatic drainage.5 These low-pressure capacitance vessels are easily compressed by the expanding hematoma while the arterial vessels continue to pump blood into the laryngeal soft tissue, tongue, and posterior pharynx. As the back pressure increases, plasma leaks out of these vessels and diffuses into the surrounding tissues, which further accelerates the compression of the veins and lymphatics in a rapidly worsening feedback loop. It is important to note that the degree of edema does not necessarily correlate with the degree of external swelling and may not resolve immediately upon clot evacuation, making diagnosis and treatment more challenging.5

Finally, communicating neck spaces promote the expansion of the bleeding with worsening edema secondary to blood dissection along tissue planes.5 Thus, when evaluating a patient with ANH, it is important to keep in mind that sudden and catastrophic airway compromise can occur without warning. It is, therefore, paramount to be ready with difficult airway, suture removal, and tracheotomy equipment. Although the patient in the case presented was sent to CT scan for evaluation, this practice may not be advisable given the lack of close monitoring of the patient while in the scanner and the delays that may result from transport and imaging time. Use of bedside ultrasound may be a better alternative as it is often more accessible and familiar to anesthesia professionals to assess the internal structures of the neck for size and location of hematoma, degree of tissue edema, and patency of the airway.17

Timely recognition and intervention of a developing ANH is potentially lifesaving. All providers caring for such patients should, therefore, be well versed in understanding the signs and symptoms of ANH leading to airway obstruction (Table 2) and be trained to intervene rapidly. Several factors that may contribute to a delay in making the diagnosis include opaque dressing, C-collar, infrequent exams, and overall lack of vigilance and/or awareness.

Table 2: Anterior Neck Hematoma—Signs & Symptoms

| EARLY | LATE |

| Increased neck pain | Difficulty or painful swallowing/drooling |

| Asymmetry of neck | Facial edema |

| Change in neck circumference | Enlarged tongue |

| Change in drain output | Tracheal deviation |

| Tightness of neck | Convexity of neck |

| Hypertension | Shortness of breath/tachypnea |

| Discoloration of neck | Stridor |

| Agitation | |

| Tachycardia | |

| Voice change |

Management

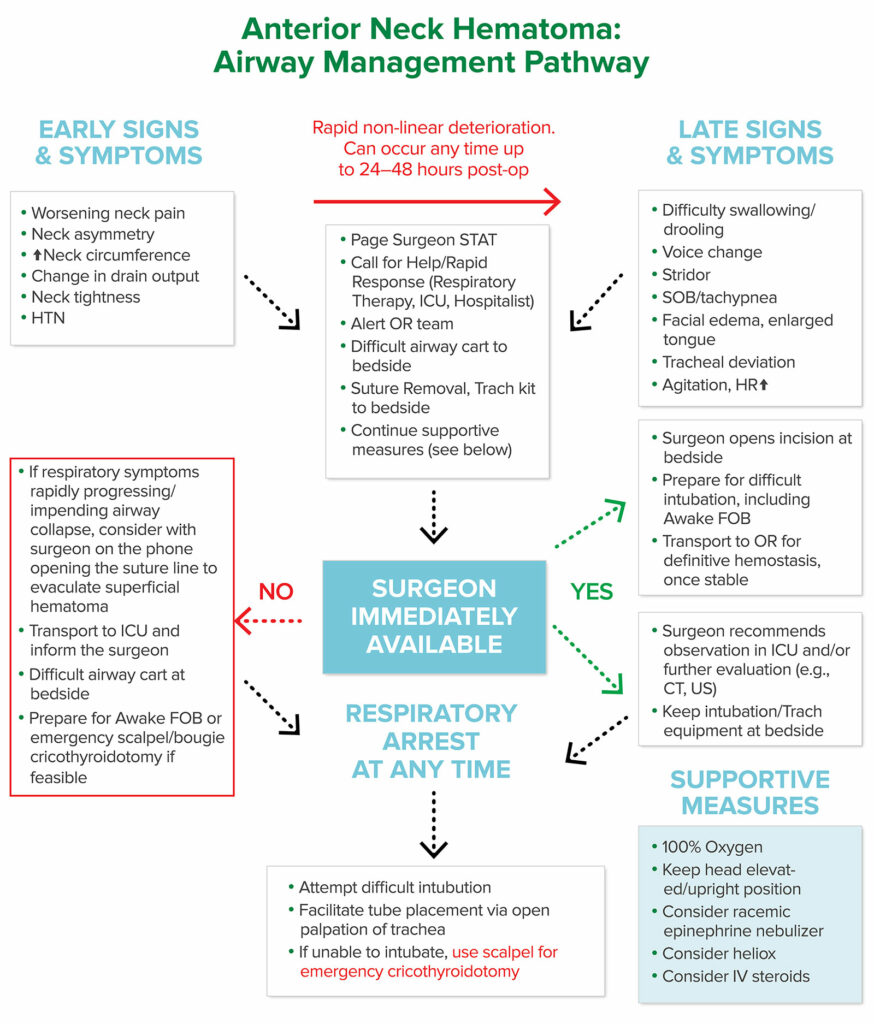

To assist with prompt clinical management of the ANH patient we have developed an algorithm which in our opinion proposes a care pathway for patients with ANH (Figure 2). This algorithm has not yet been published or clinically validated.

Figure 2: Anterior Neck Hematoma: Airway Management Pathway.

Abbreviations: CT (Computed tomography), FOB (Fiberoptic bronchoscopy), ICU (Intensive Care Unit), IV (Intravenous), HTN (Hypertension), HR (Heart Rate), OR (Operating Room), SOB (Shortness of breath), US (Ultrasound).

Prompt notification and evaluation by the surgical team should occur as soon as ANH is suspected. Prior to more invasive interventions, supportive measures such as head elevation, administration of 100% oxygen or Heliox, intravenous steroids, and/or inhaled racemic epinephrine may be beneficial.5

Flexible fiberoptic nasopharyngo-video-laryngoscopy using a 6 mm scope (for adults) or 1.99 mm (pediatrics) can be useful to identify displacement of the larynx, degree of laryngeal edema, location, and size of any mass.

Caution must be exercised, however, when performing any procedure on these patients, as similar to patients with epiglottitis, ANH patients are susceptible to full airway collapse.18 In those patients with a very narrow airway lumen and high air flow resistance (breathing through a narrowed orifice), the work of breathing may be significantly increased, resulting in hypoventilation and elevated carbon dioxide levels. As a result, any actions that increase pain and/or anxiety and, therefore, elevate blood pressure, heart rate, or oxygen consumption can lead to respiratory arrest.

As exhibited by the patient in the case study presented here, new onset of anxiety and agitation may also be signs of hypercarbia and/or hypoxia and, therefore, impending airway compromise. If a surgeon is not immediately available, an anesthesia professional may be called upon to evacuate the hematoma and secure the airway while waiting for a surgeon to arrive. In the absence of a surgeon, opening the suture line and evacuating the hematoma may be the only recourse to prevent and/or relieve total airway obstruction.

Furthermore, in the event of total airway collapse, a percutaneous (needle) cricothyroidotomy may not be sufficient to reestablish a patent airway due to anatomic distortion. In such a circumstance, a surgical cricothyroidotomy may be the only effective means to reestablish an airway, due to a completely swollen neck with distorted landmarks.1,4,8

We recognize that anesthesia professionals may not be comfortable performing these invasive surgical procedures, and, therefore, we recommend simulation training and other hands-on education be undertaken proactively. Based on our experience, in emergency situations such as this, omission bias may be an obstacle resulting in delayed care.9 The following two suggestions may bolster one’s level of confidence, overcome omission bias, and empower the anesthesia professional to perform these lifesaving interventions:

- call for help from an in-house physician, preferably someone with some form of airway expertise

- have the surgeon on the phone while one performs such maneuvers for guidance and support.

Depending on the clinical presentation of the patient, a decision must be made as to whether invasive interventions are needed immediately, or whether one has time to observe and/or wait for a surgeon to arrive and evaluate.

The following questions should be asked:

- Should the suture line be opened or a more aggressive hematoma evacuation be performed?

- Should a more definitive airway be placed, such as an endotracheal tube? And, if so, should this be done with the patient awake or asleep?

Given that total airway collapse can occur at any time, one must always be prepared to establish a surgical airway.8 Plans need to be weighed carefully and communicated to everyone involved (Table 3).

Table 3:

| QUESTIONS | OPTIONS |

| WHAT? |

|

| WHEN? |

|

| WHERE? |

|

| HOW? |

If asleep:

|

Conclusion

Complete airway obstruction of an ANH can be rapid and without warning, with non-linear and unpredictable progression. To deliver safe patient care, a clear understanding of the pathophysiology of ANH by all providers caring for patients undergoing procedures of the neck are key to prompt and appropriate management of this insidious and potentially fatal clinical complication. Anesthesia professionals should be prepared to intervene in such cases when a surgeon is not immediately available, and, therefore, should be familiar with and train to perform surgical techniques that generally fall outside of our usual skill sets.

Madina Gerasimov, MD, MS, is assistant professor at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell; site director, Quality Assurance, North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, NY.

Brent Lee, MD, MPH, FASA, is director of Clinical Excellence and Performance Improvement, North American Partners in Anesthesia (NAPA).

Edward A. Bittner, MD, PhD, is associate professor of anesthesiology, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, and is associate editor of the APSF Newsletter.

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Hung O, Murphy, M. Airway management of the patient with a neck hematoma. In: Hung’s Difficult and Failed Airway Management. [online] New York: McGraw Hill, 3rd ed. 2018.

- Shah-Becker S, Greenleaf EK, Boltz MM, et al. Neck hematoma after major head and neck surgery: risk factors, costs, and resource utilization. Head Neck. 2018;40:1219–1227.

- Zhang X, Du W, Fang Q. Risk factors for postoperative haemorrhage after total thyroidectomy: clinical results based on 2,678 patients. Sci Rep. 2017;1:7075.

- Bittner EA. Silent pain in the neck. [online] USDOH Patient Safety Network. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/webmm/case/235/Silent-Pain-in-the-Neck. Accessed December 12, 2020.

- Law J. Chapter 55. Management of the patient with a neck hematoma. In: Hung O, Murphy MF. Eds. Management of the Difficult and Failed Airway, 2e. McGraw-Hill; https://accessanesthesiology.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=519§ionid=41048448 Accessed November 17, 2020.

- Baribeau Y, Sharkey A, Chaudhary O, et al. Handheld pointof-care ultrasound probes: the new generation of POCUS. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:3139–3145.

- Lichtor JL, Rodriguez M0R, Aaronson NL, et al. Epiglottitis: it hasn’t gone away. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:1404–1407.

- Heymans F, Feigl G, Graber S, et al. Emergency cricothyrotomy performed by surgical airway–naive medical personnel. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:295–303.

- Stiegler MP, Neelankavil JP, Canales C, et al. Cognitive errors detected in anesthesiology: a literature review and pilot study. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:229.

- Sagi HC, Beutler W, Carroll E, et al. Airway complications associated with surgery on the anterior cervical spine. Spine. 2002;27:949–953.

- Bononi M, Amore Bonapasta S, Vari A, et al. Incidence and circumstances of cervical hematoma complicating thyroidectomy and its relationship to postoperative vomiting. Head Neck. 2010;32:1173–1177.

- Shun-Yu C, Kun-Chou H, Shyr-Ming S-C, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of bilateral subtotal thyroidectomy versus unilateral total and contralateral subtotal thyroidectomy for Graves’ Disease. World Journal of Surgery. 2005;29:160–163.

- Yu NH, Jahng TA, Kim CH, Chung CK. Life-threatening late hemorrhage due to superior thyroid artery dissection after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E739–742.

- Dehal A, Abbas A, Hussain F, et al. Risk factors for neck hematoma after thyroid or parathyroid surgery: ten-year analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample database. Perm J. 2015 Winter;19:22–28.

- Rosenbaum M A, Haridas, M, McHenry CR, Life-threatening neck hematoma complicating thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Am J Surg. 2008;195:339–343.

- Self DD, Bryson GL, Sullivan PJ. Risk factors for post-carotid endarterectomy hematoma formation. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:635–640.

- Kua JS, Tan IK. Airway obstruction following internal jugular vein cannulation. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:776–780.

- Yu NH, Jahng TA, Kim CH, Chung CK. Life-threatening late hemorrhage due to superior thyroid artery dissection after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E739–742.

- Pei-Ju W, Siu-Wah C, I-Cheng L et al. Delayed airway obstruction after internal jugular venous catheterization in a patient with anticoagulant therapy. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2011;2011:359867.

- Mishio M, Matsumoto T, Okuda Y, et al. Delayed severe airway obstruction due to hematoma following stellate ganglion block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:516–519.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF