Scaling and sustaining change in healthcare is complex and generally requires alignment of interdisciplinary groups on multiple levels. Some of the most successful efforts have used a “learning collaborative” to focus on a specific patient safety priority over an extended period of time. This type of organizational macro-ergonomic facilitates alignment of context experts (clinicians), subject matter experts (e.g., human factors, implementation science, systems engineering, information technology), and organizations that promote patient safety. The Perioperative Multi-Center Handoff Collaborative (MHC) is a national learning collaborative whose primary objective is to create pragmatic, scalable, and sustainable solutions for increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of patient handoffs and care transitions. A significant, tangible result of MHC’s collaborative partnership model across industry (i.e., with an electronic health vendor) was the successful design of an intraoperative handoff tool that was incorporated into the electronic medical record system and made available to all users nationally within 18 months.

Updates from the Perioperative Multi-Center Handoff Collaborative (MHC)

Scaling and sustaining change in health care is complex and generally requires aligning the efforts of interdisciplinary groups on multiple levels. Examples include the use of participatory design to adapt a best practice to a given clinical unit, forming guidance teams to scale successful unit-based efforts throughout a hospital or health system, and incentivizing wide-spread dissemination of effective implementation strategies by medical societies, large group practices, and regulatory and funding agencies. Some of the most successful efforts to date have used a “learning collaborative” to focus on a specific patient safety priority over an extended period of time. This type of organizational macro-ergonomic facilitates alignment of context experts (clinicians), subject matter experts (e.g., human factors, implementation science, systems engineering, information technology), and organizations that promote patient safety. The Michigan Keystone Project (for central lines)1 and the Safe Surgery program in South Carolina (for surgical checklists)2 are two such exemplars, though other examples continue to emerge.

The Perioperative Multi-Center Handoff Collaborative (MHC) is a national learning collaborative whose primary objective is to create pragmatic, scalable, and sustainable practices that will increase the efficiency and effectiveness of handoffs and care transitions for clinicians, patients, and their families. It was formed in 2015 by a group of academic anesthesiologists who were leading pilot efforts at their respective institutions. A partnership with the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) led to the planning and conduct of the first Stoelting Consensus Conference on Perioperative Handoffs in 2017. This interprofessional conference of patient safety experts achieved high levels of consensus over 50 recommendations3 that laid the foundation for the formation of the MHC’s initial working group on education, implementation, and research. The collaborative relationship was solidified when APSF sponsored the MHC as its special interest group (SIG) for championing handoffs and care transitions, one of its patient safety priorities (#7 Handoffs & Care Transitions).4 This support was instrumental for the launch of MHC’s website (www.handoffs.org), which is intended to increase visibility and connect its members to other medical societies, industry, medical groups, insurers, and regulatory agencies.

As a boundary-spanning organization, the MHC seeks to accelerate the development of scalable solutions for handoffs through experimentation and thoughtful expansion of its collaborative partnerships. Although its membership now comprises a substantial interdisciplinary “brain trust” that represents more than 20 academic medical centers within the United States, strategic partnerships will be required to generate products for discovery (grants, manuscripts), multilevel education (curriculum), and implementation (tools, strategies) for both the public and private sectors. One such example is the collaborative partnership created in 2018 with Epic, the electronic medical record (EMR) vendor for over half of the institutions providing anesthesia in the United States. Given growing evidence of a relationship between number of handoffs and morbidity and mortality,5-7 the MHC’s Implementation Working Group began working with an Epic Foundation team to design a platform that would improve the intraoperative anesthesia handoff process. Here we describe the process and achievements of that collaboration.

After official formation of the MHC, our EMR workgroup first met in December 2017. The core members consisted of the Epic team—Felix Lin, Adam Marsh, and Spencer Small—along with anesthesiologists from different institutions: Philip Greilich, MD (UT Southwestern, MHC founding chair), Aalok Agarwala, MD (Massachusetts General, MHC steering board member), Patrick Guffey, MD (Children’s Hospital of Colorado, Epic Steering Committee), Guy De-Lisle Dear, MD (Duke), Trent Bryson, MD (UT Southwestern), and Bommy Hong Mershon, MD (Johns Hopkins). We met monthly over the next two years, with additional members joining throughout. Our workgroup’s goal was to design an intraoperative handoff tool in Epic through this collaborative partnership.

Initially, we compared each institution’s own intraoperative handoff tools in Epic: what worked, what needed improvement, and the limitations that our local Epic programmers encountered. Led by Felix Lin (Epic), we surveyed the clinicians in our group on the critical and necessary elements that needed to be in an intraoperative handoff tool. Based on this information, our design approach was to reduce clutter, streamline the most crucial information elements essential to an intraoperative handoff, and minimize the “clicking” and “scrolling” that was prevalent when navigating within the Epic intraoperative record. It was also important that we incorporate mandatory documentation such as the staffing time grid when the handoff occurs. We applied quality improvement principles of standardizing critical information elements8,9 and integrated these guidelines into the workflow to ultimately make it accessible and easy to use. However, institutions could customize the specific data points displayed within the different standardized critical information elements according to the their specific workflow and preference in a process considered “adapting standard work to individual customers.”10

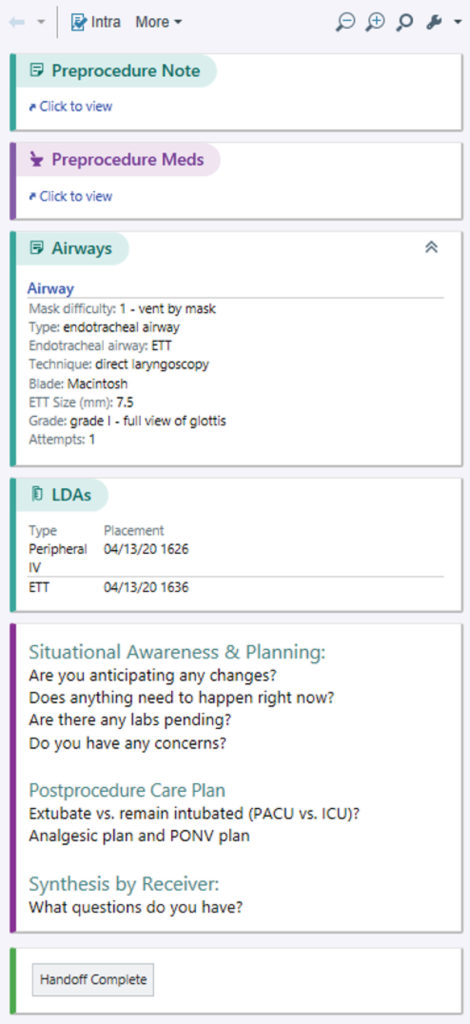

Figure 1: First version of the intraoperative handoff tool (reprinted with permission from ©2020 Epic Systems Corporation) in the Epic intraoperative record.

We also recognized that good handoff communication is not just about information transfer. The most important factor for successful handoffs is interactive communication, supported by the cognitive load theory of working memory.11 Our consensus was to add a static text box to prompt the handoff giver and receiver to engage with each other.

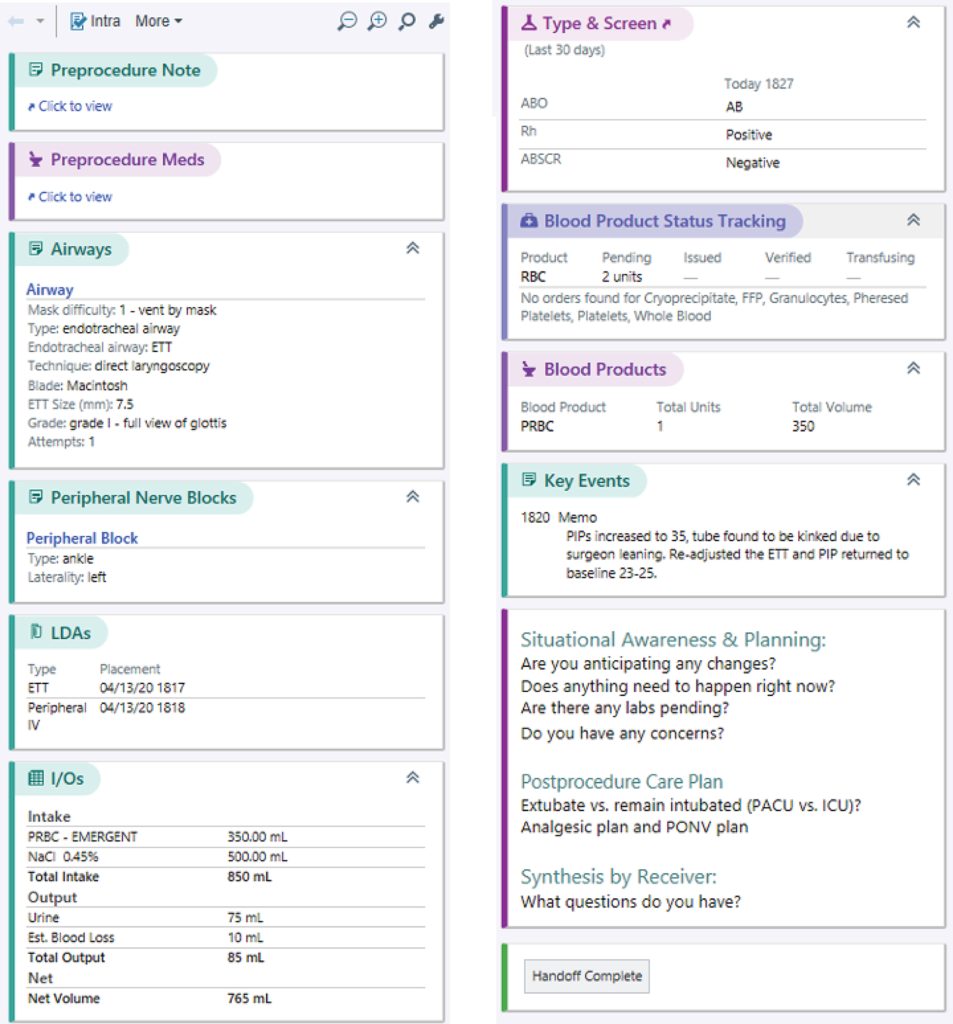

Within 18 months of forming this collaborative partnership, Epic was able to launch the first official version (Figure 1) of the handoff tool in August 2019. The latest version (Figure 2), released in February 2020, contains additional information elements. This handoff tool was disseminated to more than 50% of all Epic customers in this short time.

Because of limitations related to programming and internal review within Epic, these versions do not include all of the elements our group had originally designed and requested. Epic developers decided to focus on creating a tool that offered the available elements in the most user-friendly format for easier adoption by more institutions. Our group is continuing to work with Epic to further refine this tool and to develop a set of user requirements that could be adopted by other EMR vendors.

Moving forward, our goals are to 1) improve the functionality of the Epic mobile version, or Haiku, in a way that makes viewing a patient’s record more clinician-centered and enables it to be used for handoffs and 2) focus on the operating room to postanesthesia care unit and operating room to intensive care unit (ICU) handoffs. Future plans include expansion to improving handoffs in other perioperative environments such as ICU, ER, floor to OR handoffs.

Complex health processes such as handoffs benefit greatly if we approach them through collaborative partnerships. Design, implementation, and dissemination of guidelines, best practices, and tools can be achieved more efficiently and effectively and thereby help improve health care at the national level. A national conference, funded by the Agency for Healthcare, Quality and Research (AHRQ), is scheduled to convene in 2021 to bring major stakeholders together to plan scalable solutions for teaching, implementing, and investigating best practices for perioperative handoffs and care transitions.

Figure 2: Current version of the handoff tool (reprinted with permission from ©2020 Epic Systems Corporation) in the Epic intraoperative record. In the live Epic intraoperative record, this sidebar is shown as a continuous vertical column that can be viewed by scrolling up and down.

Bommy Hong Mershon, MD, is assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Philip E. Greilich, MD, MSc, is professor in the Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Management at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reames BN, Krell RW, Campbell DA, et al. A checklist-based intervention to improve surgical outcomes in Michigan. JAMA Surg. Published online 2015. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2873 Accessed January 11, 2021.

- Donahue B. In South Carolina, proof that surgical safety checklist really works. Outpatient Surgery Magazine. http://www.outpatientsurgery.net/newsletter/eweekly/2017/04/18/in-south-carolina-proof-that-surgical-safety-checklist-really-works#:~:text=At the heart of Safe,incision of the skin (%22time Accessed July 21, 2020.

- Agarwala AV, Lane-Fall MB, Greilich PE, et al. Consensus recommendations for the conduct, training, implementation, and research of perioperative handoffs. Anesth Analg. Published online 2019. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004118 Accessed January 11, 2021.

- APSF’s Perioperative Patient Safety Priorities. apsf.org. Published 2018. https://www.apsf.org/patient-safety-initiatives/ Accessed November 12, 2020.

- Hyder JA, Bohman JK, Kor DJ, et al. Anesthesia care transitions and risk of postoperative complications. Anesth Analg. Published online 2016. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000000692 Accessed December 21, 2020.

- Jones PM, Cherry RA, Allen BN, et al. Association between handover of anesthesia care and adverse postoperative outcomes among patients undergoing major surgery. JAMA. Published online 2018. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.20040 Accessed December 21, 2020.

- Saager L, Hesler BD, You J, et al. Intraoperative transitions of anesthesia care and postoperative adverse outcomes. Anesthesiology. Published online 2014. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000401 Accessed December 21, 2020.

- Rozich JD, Howard RJ, Justeson JM, et al. Standardization as a mechanism to improve safety in health care. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. Published online 2004. doi:10.1016/S1549-3741(04)30001-8 Accessed December 21, 2020.

- Quisenberry E. How does standard work lead to better patient safety. https://www.virginiamasoninstitute.org/how-does-standard-work-lead-to-better-patient-safety/ Accessed December 21, 2020.

- Goitein L, James B. Standardized best practices and individual craft-based medicine: a conversation about quality. JAMA Intern Med. Published online 2016. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1641 Accessed December 21, 2020.

- Young JQ, Wachter RM, Ten Cate O, et al. Advancing the next generation of handover research and practice with cognitive load theory. BMJ Qual Saf. Published online 2016. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004181 Accessed December 21, 2020.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF