Medication errors causing harm to patients in the operating room remain a persistent problem. To develop new strategies for “predictable prompt improvement” of medication safety in this setting, the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) convened a multidisciplinary consensus conference on January 26, 2010. The conference called for a “new paradigm” for future safety efforts to include 4 critical elements: Standardization, Technology, Pharmacy / Prefilled / Premixed, and Culture (STPC).

Medication errors causing harm to patients in the operating room remain a persistent problem. To develop new strategies for “predictable prompt improvement” of medication safety in this setting, the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) convened a multidisciplinary consensus conference on January 26, 2010. The conference called for a “new paradigm” for future safety efforts to include 4 critical elements: Standardization, Technology, Pharmacy / Prefilled / Premixed, and Culture (STPC).

The recent intravenous (IV) infusion safety initiative at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center provides an excellent illustration of how implementing the new paradigm can successfully improve medication safety, clinician satisfaction, and operational efficiency from the operating room to post-operative care. One anesthesiologist described the initiative as “the smoothest implementation of a new technology” in his entire career. Selection and implementation of a new “smart” IV infusion safety system with syringe and large-volume pumps on a common platform was the catalyst for standardizing infusion technology, drug libraries, concentrations, dosing units, and dosage limits Medical-Center wide.

In this case study, operating-room and intensive-care IV infusion therapy at Wake Forest Baptist before and after the initiative, the change process, lessons learned, and results achieved through the implementation of STPC are reviewed.

NEED TO IMPROVE IV MEDICATION SAFETY

At Wake Forest Baptist, an 872-bed academic medical center in Winston-Salem, NC, variability in infusion pumps and medication use negatively affected both operating rooms and intensive care units (ICUs). Inconsistencies created difficulties for pharmacy in preparing the medications and for ICU nurses in managing patient care, e.g., when they had to set up new infusions, switch from syringe to drips, and calculate dosages using different concentrations and dosing units.

Staffs for cardio-thoracic (CT) surgeries, anesthesia and ICU medical, nursing and pharmacy had previously collaborated on process improvements, e.g., standardizing inotrope use by sharing the syringe pumps. Transitions were still required for non-standard concentration drips and large-volume drips such as lidocaine and amiodarone, which anesthesia often infused by syringe. Admitting a CT-ICU patient could take 20 minutes or longer, and patients could become hyper- or hypotensive as a result of the changes.

With unstable patients, nurses delayed switching from syringes to drips and had to use different technology from what they routinely used. Syringe pumps were supposed to go back to the operating room, but frequently anesthesia providers could not find proper pumps for operating room care. Variable pump programming increased frustration. Anesthesia staff members were dissatisfied with ICU volumetric infusion (used throughout non-operating room areas) and often discarded those drips for their own syringe infusions, after transporting patients into the operating room.

Pharmacy prepared some IV medications, and concentrations may have differed, depending on anesthesiologists’ preferences. Materials management struggled with hoarding, misplaced pumps and misplaced detachable electrical plugs. Changing the drug libraries in the large-volume pumps would have required manually uploading changes to each individual pump—if they could all be found. Syringe pumps were not “smart” (computerized), and site-specific infusion-mode options varied among the pumps.

In operating rooms, ICUs, pharmacy, and central supply, lack of standardization increased waste, inefficiencies, clinician stress, the potential for errors and, most importantly, the possibility of patient harm.

Accomplishing Change

Throughout 2007 frustration with lack of standardization increased. In addition, the syringe pumps were going out of service and would no longer have vendor support. The contract for the large-volume pumps was going to expire.

In November 2007 and February 2008 ECRI published articles on the advantages of new “smart” infusion technologies, including a modular IV infusion safety system that combined syringe and/or drips on a common platform with robust dose-error-reduction software (DERS).1-3 The multidisciplinary Wake Forest Baptist Infusion Pump Utilization Committee, with representatives from anesthesia, materials management, nursing, pharmacy, and risk management, decided to organize infusion pump trials and a formal pump evaluation to obtain staff feedback on various technologies. The modular system’s apparent bulkiness was a concern, and no consensus was reached.

A similarly representative Wake Forest Baptist team visited local hospitals that used various technologies, and then traveled to several medical centers using the modular system. Staff at those medical centers reported that the modular system was effective and easy to use, even in smaller operating rooms, and strongly supported the standardization concept.

These visits convinced the Wake Forest Baptist team that it could achieve what it wanted to accomplish. Senior leadership was willing to purchase as many pumps as necessary to standardize infusion therapy and prevent hoarding. In May 2009 Wake Forest Baptist announced that the modular IV medication safety technologya would be implemented throughout the Medical Center.

Key deciding factors for this group were recommendations in the unbiased literature1-3 and the combination of volumetric and syringe infusion pumps on a single platform with a common user interface. The new technology would allow operating rooms and the rest of the Medical Center to use the same robust IV medication safety system. “Go-Live” was set for February 2, 2010, leaving 9 months to prepare.

Standardization / Pharmacy

APSF has long recommended standardizing medication use to reduce opportunities for error. The Wake Forest Baptist implementation team was now convinced that standardizing IV medications hospital-wide—concentrations, dosing units, method of infusion (syringe or drip)—was desirable and possible. Standardization was fully supported by Wake Forest Baptist’s Chief Medical Officer, Chief Pharmacy Officer, Chief Nursing Officer, Chiefs of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Emergency Medicine, ICU nurses, pharmacists, and critical care, anesthesia and emergency physicians.

Two teams were established to standardize adult and pediatric concentrations. Standardization efforts were spearheaded by the anesthesiologist who chaired the Anesthesia Department Equipment Committee and who had chaired the APSF Committee on Technology. The vendor provided extensive technical and training support in helping pharmacy set up the drug library and helping staff scrutinize practices to identify possible improvements.

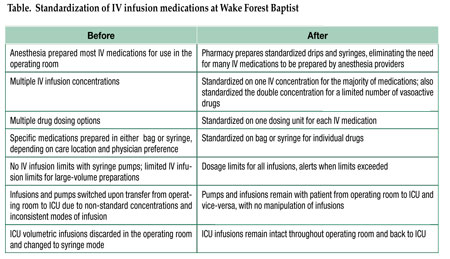

Multiple iterations and faculty and staff reviews resulted in a list of standardized concentrations, dosing units, dosage limits, and method of infusion (syringe or pumps). Drug preparation and method of infusion would remain unchanged from the operating room to the ICU and vice-versa. Some drugs would only be available for use by anesthesia professionals. No local anesthetics were to be delivered by infusion pumps outside the operating room. For a limited number of vasoactive drugs, the double concentration (2X) was also standardized. Weight-based or non-weight-based dosing was largely determined by anesthesiology and critical care attending physicians. (See Table.)

In October 2009 anesthesia providers were concurrently and cooperatively presented with a draft list of the medications pharmacy would prepare for use in operating rooms and ICUs, eliminating the need for anesthesia to formulate their own vasoactive, sedative, insulin and other drips. Pharmacy, anesthesia, nursing, ICU, emergency department and faculty directors met with the standardization committee and gave their support.

The final Go-Live version of the data set was distributed by pharmacy on December 4, 2009 and the data were entered into the DERS drug libraries. Shortly before Go-Live, anesthesia prepared a single-page summary that showed the concentration, method of infusion, dosage limits, bolus range, bag versus syringe, and “anesthesia only” for every anesthesia drug. This was laminated and placed in the operating rooms as a ready reference.

Technology

The modular design of the new infusion safety technology with DERS combines syringe and large-volume pump modules on a common user interface, eliminating the need for different systems in anesthesia, critical care and general nursing. Hospital-defined “profiles” in the software adjust pump settings to meet the needs of particular patient care areas or patient types. Each profile has a hospital-defined drug library with standardized drug names, concentrations, diluents, dosing units, and maximum-minimum dose and bolus limits. If programming exceeds the pre-established limits, the software provides a “soft” (can be overridden) or “hard” (cannot be overridden) alert that must be addressed before infusion can begin.

“Anesthesia mode” allows providers to access anesthesia-specific drugs, concentrations and limits. Alerts, dosage limits, infusion “pause,” clinical advisories and other settings are customized for anesthesia use. After surgery, when the system is unplugged from AC power, it automatically reverts to nursing mode. All running infusions continue at the anesthesia-mode rate/dose and dosing units until reprogrammed by the nurse.

The infusion system stays with the patient and allows easy selection of either syringe or large-volume pumps. If the current infusion completes, a new infusion container of the same drug/concentration can be hung, a new volume-to-be-infused established, and the infusion continued. If a patient returns to the operating room, the anesthesia provider can quickly return to anesthesia mode without interrupting the infusion or doing any additional programming.

Each infusion system is automatically connected to the hospital’s wireless communication system, facilitating the rapid transfer of an updated drug library, if new drugs are added or dose limits adjusted. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) data logs provide data on “alerts” (dosage limit has been exceeded) and averted errors (alert resulted in reprogramming or canceling the infusion). CQI data are wirelessly transferred to the infusion system server, allowing analyses to be performed by hospital staff or the vendor to help identify opportunities for improving IV medication safety and best practices.

Culture

A major factor contributing to the implementation’s success was the very strong culture of cooperation, respect, dedication, and decency at Wake Forest Baptist. Leaders have the respect of their people, who want to see them succeed. Everyone engaged in this effort from an overall standpoint of safety. Instead of the “silo” approach found in many medical centers, there was a well-functioning team, albeit one that required deliberation and vetting. Throughout the standardization process, there was give-and-take and real compromise. Anesthesia got some things they really wanted, as did pharmacy and nursing. The end result was win-win, and people are happy with the outcome.

Staff members were involved from the very beginning. When it came time to implement the system, an overwhelming majority of staff was trained, which was key. Now everyone knows how to use both syringes and drips, so when a patient is taken to their post-operative destination, the pumps stay right with that patient with no interruption or changeover to another system.

Training

Based on previous experience the implementation team recognized that training had to be mandated to have everyone attend. They got this commitment from the senior leadership, department heads, and others. Every clinician was told by their leadership that this was going to be the new pump, implementation will occur at a specific hour, no exceptions.

Training included hands-on experience, lectures, and 75 two-hour workshops held day and night (e.g., 2:00 a.m.) so all could attend. Workshops were designed so that everyone had his or her own pump. The instructor covered material rapidly to keep attendees invigorated and excited. The consensus opinion stated that all who took the training found the new pumps easy to use, and many said good things about the pumps, which encouraged others to attend and built excitement. A few Wake Forest Baptist physicians had come from a hospital where they had been using the modular system, so they also spoke to how standardization on the new system would work.

Installation

Months before Go-Live the vendor’s project manager helped develop a schedule and held vendor and hospital staff accountable for staying on track. Vendor representatives checked the devices, ensured the profiles and drug libraries were properly loaded into the DERS, all the electrical safety checks were done, and that everything needed was there.

A pre-Go-Live meeting was held on February 1, and a final memo and reminders with HELP listings and numbers sent to anesthesia staff. On February 2, 2010, the Go-Live was implemented successfully. The technical support team from the vendor helped ensure that timelines were met, devices were moved into place, pumps were working properly, and connectivity was working in all areas of the Medical Center. Post-implementation meetings were held to discuss the few difficulties, and the vendor sent updates to all staff responding to any concerns.

Results

- The new IV medication safety system with syringe and large-volume pumps on a common platform is now used throughout Wake Forest Baptist, with the specialized “anesthesia mode” used in the operating room.

- Drug concentrations and dosing units are standardized across the Medical Center (Table).

- Bags using standard concentrations for the operating room are prepared by pharmacy.

- Medications that are still delivered via syringe for the operating room (e.g., narcotics, amnestics) are drawn directly out of single-use vials and may require dilution.

- IV infusion pumps used in the operating room remain with the patients upon transfer to critical care and vice-versa.

- Nurses no longer switch out infusion pumps and medications or tear down lines, decreasing ICU patient admission time from an estimated 20 minutes to 5 to 10 minutes.

Lessons Learned

- Find champion workers among respected thought leaders.

- Do careful needs assessment before selecting a new system.

- Do a detailed analysis to determine how many devices are needed, before going through the purchase agreement.

- Involve nurses in the selection process and throughout implementation.

- Allow plenty of opportunities for as many clinicians as possible to provide input into the creation of the drug library.

- Have leadership support standardization and emphasize (mandate) training.

- Educate, train, educate, and train end users.

- With pharmacy preparing all drips for anesthesia, make sure the drips are always available, especially at night.

- Have enough medication on hand for an anesthesia provider to make the proper dilution, when pharmacy-prepared bags are not readily available off-hours (e.g., an epinephrine drip at 3 am).

Discussion

The leadership team professed that the implementation of the new modular IV infusion safety system was one of the easiest, well-planned, well-organized, and coordinated implementations Wake Forest Baptist has ever done, especially one of this size. The technology’s features catalyzed an overhaul of the system that otherwise might not have happened. The successful implementation depended on the hospital’s support of all 4 pillars of the new medication-safety paradigm:

Standardization – Extensive staff involvement and multiple iterations resulted in agreement on a single administration mantra for each drug.

Technology – Being able to combine all pumps into a single user interface allowed all areas to use the same system.

Pharmacy – The Department of Pharmacy prepares standardized drips and syringes, eliminating the need for many medications to be prepared by anesthesia providers.

Culture – Most importantly, the Wake Forest Baptist culture of safety and dedication to patients’ best interests enabled the entire team to collaborate to achieve this success.

Conclusion

At Wake Forest Baptist implementation of the new user-friendly infusion safety technology with syringes and drips on a common platform achieved highly positive results. IV medication use was standardized throughout the hospital system. Staff moved from focusing on their own dealings with individual patients to a more global awareness of patient and medication safety implications outside the operating room and throughout the hospital.

As a result of implementing the 4-pronged approach of STPC, Wake Forest Baptist improved IV medication safety, clinician satisfaction, and operational efficiency, not only in the operating room and post-operative care but also Medical Center-wide.

Acknowledgements:

Dr. Vanderveen is Vice President, Center for Safety and Clinical Excellence, CareFusion, San Diego, CA. He serves on the APSF Board of Directors and is a member of the APSF Committee on Technology. Ms. Graver is Senior Medical Writer with CareFusion, San Diego, CA. Affiliated with Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, are Dr. Noped, Assistant Director of the Pharmacy, Infusion Pump Utilization Committee Co-manager; Dr. Olympio, Tenured Professor of Anesthesiology, Chair of the Anesthesia Department Equipment Committee, and former Chair of the APSF Committee on Technology; Ms. Petree, Director of Nurse Anesthesia, Director of Clinic Operations, Operating Room; Ms. Simpson, Director of Materials Management; Mr. Sizemore, Central Services Manager, Infusion Pump Utilization Committee Co-manager, and Ms. Williamson, Nursing Unit Manager, Cardiothoracic ICU.

References

- ECRI Institute. General-purpose infusion pumps. Health Devices. October 2007:309-36. Update, November 2007.

- ECRI Institute. Syringe infusion pumps with dose error reduction systems. Health Devices. February 2008;37(2):33-51.

- ECRI Institute. Infusion pump criteria. Health Devices. February 2008;37(2):52-8.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF