Note: This article offers a reminder and a template to facilitate standard written communication of a patient’s difficult airway as recommended by the ASA difficult airway taskforce.

Introduction /Historical Perspective

Difficult airways happen. Difficult intubations have variably been reported to range from 1-18% in the operating room.1 Although the incidence is unknown, some patients also have a second or recurrent unanticipated difficult airway event. With today’s ability to communicate, there is no reason for a patient to risk having a second unanticipated difficult airway or for an anesthesia professional to suffer the stress of encountering an unanticipated difficult airway.

On several occasions I have encountered unanticipated difficult airways. One situation escalated to a “cannot-intubate, cannot-ventilate” adequately event that led quickly to a tracheotomy. Later we reviewed the patient’s history and interviewed her in detail—she was never told of any problems with her airway. However, after delving further into her history we found that several years before she had an elective outpatient surgical procedure cancelled on the table and was admitted to the hospital with a very sore throat. She was told only that she did not need the procedure after all. Would this have been our only clue?

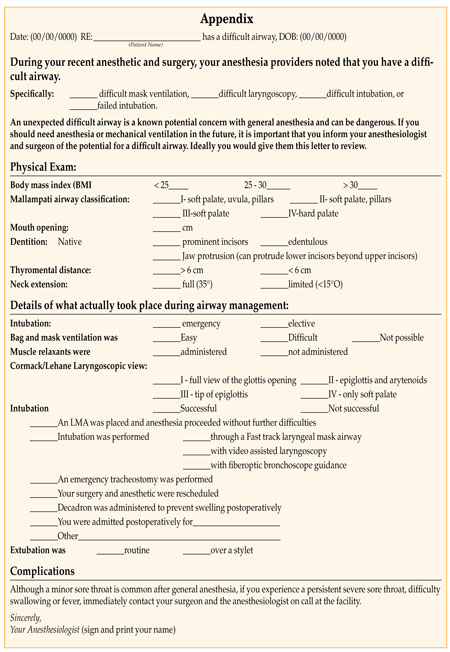

Difficult intubation is not necessarily related to difficult airway otherwise.2 Previous difficult intubation has a better positive predictive value (69-78%) than other independent predictive values. In particular, individuals with normal body habitus and exams who present with a difficult airway need to be informed precisely of the situation. We have, as a specialty, done many things to improve patient safety, one of which is to write letters for patients regarding airway difficulties encountered during their care. Since the above described encounter, I have been driven to simplify and improve the process of patient notification of a clinically occult /unknowable difficult airway. My goal is to make standardized notification the norm. A template is presented in the Appendix that can be quickly completed; it uses standard terminology to thoroughly describe the difficulty with the airway and how it was managed successfully. This can be copied and distributed to the patient, the primary care provider, the surgeon, and the facility. Such documentation facilitates effective communication of the presence and management of a difficult airway to future care providers.

The ASA Difficult Airway Taskforce published updated guidelines to facilitate management of and reduce adverse consequences of the difficult airway in 2003.3The algorithm they developed and many workshops the society has sponsored to practice its application have led to greater comfort and timely successful effective airway management of the difficult airway whether anticipated or unanticipated. This taskforce suggests the use of standard terminology to describe the difficulty with the airway: difficult facemask ventilation, difficult laryngoscopy, difficult tracheal intubation, and failed intubation . . . and elaboration on the details as necessary to convey important points to future practitioners. Prior to the practice guidelines regarding the management of the difficult airway there was little or no literature regarding benefits of patient notification of difficulty with management of their airway. The practice guidelines recommend informing the patient or responsible party of the presence of and basis for a difficult airway, unsuccessful management strategies, and successful ones. Further, in 1992 the ASA and others recommended the creation of a National Difficult Airway registry. Via numerous letters to the editor and obscure publications, anesthesiologists have given recommendations and offered templates for such notification. Their recommendations included having the patient wear an identification bracelet, registering the patient with an emergency notification service, notifying the surgeon and primary care provider, and documenting the event in the patient’s chart.

Non-standardized notification practices are common. Anesthesia providers all notify difficult airway patients in some way. Most orally inform the patient and loved ones in the PACU. However, this may not be the ideal time for this notification as the patient is somewhat sedated and the loved ones are anxious about the surgical findings and the patient’s recovery from anesthesia and surgery. In fact, 50% of patients informed orally immediately after surgery forget the information,4 which suggests that oral communication is not sufficient.

Many practitioners use a letter to notify patients of the difficult airway. This is time consuming and requires time at a computer with at least one original paragraph about the patient’s specific anatomy, techniques that worked, and those that did not. Also, if mailed later, there is no verification that the patient understands the significance of the situation.

I propose using a standardized written notification. This will force inclusion of a number of details that are part of the multifactorial prediction of a difficult airway. In addition it will allow for additional comments specific to the patient and his/her medical condition. The template presented here includes a standard introductory paragraph, a fill-in-the-blank airway exam, check boxes of the Mallampati grades5 and Cormack Lehane6 laryngoscopic views, as well as a checklist of possible approaches to the airway. There is, of course, room to add additional comments. Once completed, the original should be given to the patient or the party responsible for his or her healthcare decisions. Copies should be given to the surgeon and the primary care provider, and filed in the patient’s medical record at the facility where the event took place.

The patient and loved ones need to understand how important it is to give a copy to future anesthesia providers. John Eichhorn who founded the APSF Newsletter in 1986 states that empowering the difficult airway patient with their own health information during followup has always been a good idea, and anything you can do to advance this cause is appropriate. Making the patient responsible also bypasses all the HIPAA limitations that could be problematic with a website that allows access to the patient’s medical information. Whether the information is in a registry or in a letter, patients or their advocates must be able to tell the provider to look for the information. At the local Veterans Administration Hospital, we have the template available electronically. Once the template is entered into the patient’s electronic medical record, a posting on the patient’s cover sheet is automatically generated indicating the patient has had a difficult airway. The same process is activated for allergies and advanced directives. Also, the practitioner can add difficult airway as a diagnosis to forewarn future practitioners. A copy is printed and given to the patient. At the University of Louisville Hospital, the paper template is available in the PACU and on the difficult airway cart for manual completion. A copy is also available as an e-document, but still requires manual completion, copying, and distribution. For the medical record it must be scanned into the patient’s permanent record.

Difficult Airway Registries

Many institutions and countries, for example Denmark7 and Austria,8 have difficult airway registries with extensive standardized documentation. This works well if the patient is receiving care within the same system and the practitioner knows to check the registry. In some instances it is difficult to know the patient is part of such a registry, and even if one is informed, specific information may or may not be quickly and easily accessible to the practitioner faced with the patient’s care. Making such information universally available would violate HIPAA regulations. The patient or his healthcare advocate should be empowered to deliver the completed template as a letter or wallet card to future anesthesia providers.9.10 This obviates the need for codes and permission slips to access the information. As travelling within the country and around the world has increased, so has the incidence of receiving healthcare in facilities that have no access to medical records from previous surgeries. Using standard notification will facilitate global reporting of the exam and management strategies employed.

In summary, immediate written notification with standardized documentation of the patient’s difficult airway can prevent recurrent difficult airway events. Once completed, distribute copies of the documentation to the surgeon and the primary care provider in writing. Place a copy in the medical record of the patient in the facility where the difficult airway was first noted. Offer the patient a wallet card or medic alert ID regarding the difficult airway. Educate patients about their “difficult airway” diagnosis and empower them with their own health information to avoid recurrent personal endangerment and to protect their privacy by using a simple, thorough template containing accurate standard health terminology such as the one proposed here. Teach patients the importance of self-advocacy without scaring them. All these precautions are aimed at preventing undue risk for the patient and undue stress for future anesthesia providers. We must decrease the likelihood of a second unanticipated difficult airway event and avoid putting the patient at recurrent risk unnecessarily.

References

- Naguib M, Scamman FL, O’Sullivan C, et al. Predictive performance of three multivariate difficult tracheal intubation models: a double-blind, case-controlled study. Anesth Analg 2006;102:818-24.

- Samsoon GL, Young JR. Difficult tracheal intubation: a retrospective study. Anaesthesia 1987;42:487-90.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 2003;98:1269-77.

- Francon D, Bruder N. Why should we inform the patients after difficult tracheal intubation? Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2008;27:426-30.

- Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J 1985;32:429-34.

- Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia 1984;39:1105-11.

- Rosenstock C, Rasmussen LS. The Danish Difficult Airway Registry and preoperative respiratory airway assessment. Ugeskr Laeger 2005;167:2543-4.

- ADAIR: Austrian Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry, 1999. Available at: http://www.adair.at/. Accessed May 20, 2010.

- Mark LJ, Beattie C, Ferrell CL, et al. The difficult airway: mechanisms for effective dissemination of critical information. J Clin Anesth 1992;4:247-51.

- Trentman TL, Frasco PE, Milde LN. Utility of letters sent to patients after difficult airway management. J Clin Anesth 2004;16:257-61. Heidi M. Koenig, MD, is a Professor of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine at the University of Louisville, Louisville, KY.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF