A 61-year-old patient was urgently taken to the operating room for pelvic hardware removal. After induction, the anesthesia machine gas analyzer showed co-administration of both isoflurane and sevoflurane despite utilizing a single vaporizer. Further evaluation discovered that the sevoflurane vaporizer was incorrectly filled with isoflurane and was used in 6 prior anesthetics. Despite safety controls, it is important to remain suspicious for a misfilled vaporizer in the setting of display monitor abnormalities.

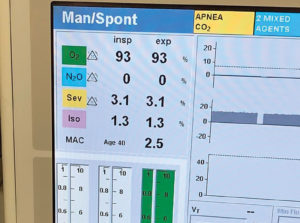

Figure 1: Dräger gas analyzer display showing both isoflurane and sevoflurane delivery when using an incorrectly filled sevoflurane vaporizer.

A 61-year-old male was urgently taken to the operating room for removal of infected pelvic hardware. Shortly after induction, both isoflurane and sevoflurane appeared on the display (Figure 1), despite only a sevoflurane vaporizer being attached to the device. The vaporizer was removed after switching to a total intravenous anesthetic to avoid the possibility of further vaporizer inaccuracies. No harm was caused to the patient.

After the surgery, biomedical engineers were unable to identify any malfunctioning components of the anesthesia machine or gas analyzer. The vaporizer was then connected to devices in different operating rooms. Specifically, the vaporizer was attached to Dräger Apollo® and Fabius® machines, and each device produced the same finding; detectable levels of both isoflurane and sevoflurane. The offending vaporizer was also replaced by a different vaporizer on the original machine and displayed appropriate sevoflurane concentrations without any detectable amounts of isoflurane. These findings confirmed that the vaporizer was filled with isoflurane.

Analysis showed the records of six previous anesthetics that had measurable amounts of isoflurane documented when administering the assumed solitary anesthetic of sevoflurane. As a result, multiple events were identified that allowed this error to persist. The initial alarm identifying the co-administration of the volatile agents was thought to be due to the gas analyzer malfunctioning, as there were no isoflurane vaporizers attached to the machine nor were any present in the room. The dismissal of an alert speaks to the breadth of alarm fatigue caused by frequent, if not constant, audible alarms in the operating room.

The importance of intraoperative handoffs cannot be overstated as well. Following a personnel change, two spinal anesthetics occurred between the identified cases. Because the contaminated vaporizer was not used, no alarms were encountered by the new providers. This allowed the error to persist to an additional unaware team that inherited the remaining cases. The anesthesia professionals and technicians involved were contacted. No source of cross-contamination with the volatile agents or problems with refilling the vaporizer were reported.

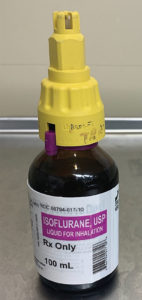

The findings were communicated to the entire anesthesia department during our monthly quality improvement conference. While we were unable to identify the exact source, the potential for the incorrect filling of a vaporizer still exists despite safety controls and device specific keys for each volatile agent and vaporizer. Although rare, circumventing these mechanisms by forcing a sevoflurane adapter onto an isoflurane volatile bottle (Figure 2) or directly pouring the contents from one to another, remains a possibility and should be on the differential if confronted with similar analyzer abnormalities. While these events did not result in patient harm, it is our hope that this case provides awareness on the persistent possibility of misfilled vaporizers.

Jonathan A. Bond, DO, MPH, is a CA-2 anesthesiology resident in the Department of Anesthesiology at West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV.

Charles Barry, MD, MSE, PE, is an assistant professor in the Department of Anesthesiology at West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV.

Nicole Hollis, DO, is an assistant professor in the Department of Anesthesiology at West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF