To the Editor:

Introduction

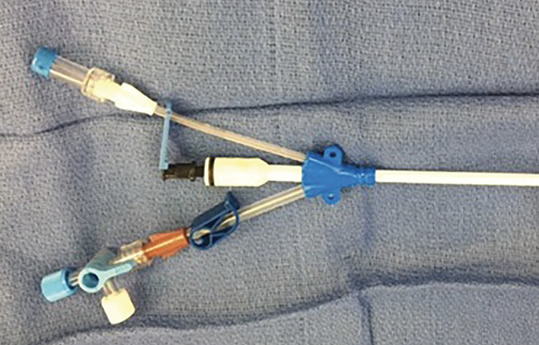

Figure 1. Central Line.

Central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) have been associated with thousands of preventable deaths and billions of dollars of additional costs to the US health care system.1 Many institutions in recent years have prioritized preventing such infections. However, a substantial number of CLABSIs continue to occur, especially in high-risk areas of the hospital. An advancement widely implemented by many institutions is the use of antimicrobial-impregnated central venous catheters (CVC) to decrease the incidence of CLABSI and its associated morbidity and excess cost.2 We report a case of an antimicrobial coated CVC that was erroneously placed in a patient, who was susceptible to an allergic reaction.

Case Report

A 33-year-old male with congenital hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy status post myomectomy and subaortic resection with aortic valve repair, presented with acutely progressive shortness of breath, lightheadedness, and chest pain. He was notably noncompliant with therapy and a poor historian. Our providers elicited a sulfa allergy but the patient was unsure of the specific reaction. He was scheduled for a surgical aortic valve replacement requiring a redo sternotomy. Central venous access was indicated for central venous pressure (CVP) monitoring and infusion of vasoactive medications post cardiopulmonary bypass.

A CVC impregnated with chlorhexidine/silver sulfadiazine was placed in the patient after the induction of general anesthesia. He did not manifest any clinical signs of an allergic response to the sulfa containing CVC. Upon identifying the error, the line was converted to a non-antimicrobial impregnated CVC before the end of the procedure. The patient was extubated on postoperative day (POD) #0 in the CTICU, weaned off vasoactive medications by POD#2, and was discharged on POD#8.

Discussion

Two types of antimicrobial coated CVCs are available on the market and for certain indications (such as CVCs expected to remain in place for >5 days in institutions where CLABSI rates are not decreasing despite implementation of CLABSI reducing strategies), carry a Category 1A recommendation from the CDC to reduce infections: minocycline/rifampin, and chlorhexidine/silver sulfadiazine.3 It has been our experience that anesthesia providers are often unaware of which specific type of antimicrobial coating is used at their institution. Furthermore, we have noted that the packaging of CVC does not clearly elucidate the risks of allergic reactions. This incident represented a medication error that resulted in a “near miss.” It also led to the separation of antibiotic and non-antibiotic coated central line catheters at our institution’s trauma and cardiac operating rooms. Their present use is based on the discretion of the surgical and anesthesia teams. Furthermore, our department as a whole became more cognizant of the indications and contraindications for antibiotic/antiseptic-coated CVC use. Other institutions may benefit from reviewing their guidelines for CVC use as this may have significant impact on patient safety.

Dr. Baja, is a anesthesiology resident at UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, CA.

Dr. Vien is a Pain Fellow at UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, CA.

Dr. Ray is Assistant Professor at UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, CA.

The authors have no financial interest or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

References:

- Liang S, Marschall J. Commentary: Update on emerging infections: news from the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2011;58:450–451. - Veenstra DL, Saint S, Saha S, et al. Efficacy of antiseptic-impregnated central

venous catheters in preventing catheter-related bloodstream infection: a meta-analysis. JAMA 1999;28:261–267. - O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, et al.The Healthcare Infection

Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections (Appendix 1). Clinical Infectious Disease 2011;52:e162–e193.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF