In the hospital, opioids are the most commonly prescribed class of medications and the second most common class of medications associated with adverse events.1,2 There are a range of adverse events associated with opioid use in the hospital. The most serious of these in terms of patient mortality is opioid-induced ventilatory impairment (OIVI). Approximately 1 in 200 hospitalized postoperative surgical patients suffer from OIVI.3 One report identified 700 inpatient deaths in the U.S. directly attributed to patient-controlled analgesia between 2005 and 2009.4 In addition to being common, and, at times, devastating to patients and caregivers alike, adverse events related to opioids are costly. In a 2011 study, annual costs in the U.S. associated with postoperative OIVI were approximately $2 billion.5 The significant impact of OIVI on patient safety and health care costs has prompted many governmental and non-governmental agencies to develop regulations and guidelines designed to reduce OIVI in the inpatient setting. One of the most recent and comprehensive of these guidelines is The Joint Commission R3 Report issued in August 2017.1

In the hospital, opioids are the most commonly prescribed class of medications and the second most common class of medications associated with adverse events.1,2 There are a range of adverse events associated with opioid use in the hospital. The most serious of these in terms of patient mortality is opioid-induced ventilatory impairment (OIVI). Approximately 1 in 200 hospitalized postoperative surgical patients suffer from OIVI.3 One report identified 700 inpatient deaths in the U.S. directly attributed to patient-controlled analgesia between 2005 and 2009.4 In addition to being common, and, at times, devastating to patients and caregivers alike, adverse events related to opioids are costly. In a 2011 study, annual costs in the U.S. associated with postoperative OIVI were approximately $2 billion.5 The significant impact of OIVI on patient safety and health care costs has prompted many governmental and non-governmental agencies to develop regulations and guidelines designed to reduce OIVI in the inpatient setting. One of the most recent and comprehensive of these guidelines is The Joint Commission R3 Report issued in August 2017.1

The R3 Report (R3 stands for Rationale, Requirement, and Reference) provides standards for inpatient pain assessment and management designed to improve quality and safety. The standards focus on safe opioid prescribing and performance improvement, minimizing treatment risk, and performance monitoring and improvement using data analysis. This review will suggest four specific ways hospitals and their medical staff can implement some of these standards to decrease the risk of OIVI.

Strategy 1: Assessment and Mitigation of Patient Risk for OIVI

When caring for postoperative patients and others receiving opioids in the hospital, clinicians must identify patients who are at high risk for developing OIVI. The history and physical exam is the mainstay for gathering important and specific knowledge about patients. Risk assessment and preoperative screening by the surgeon, anesthesia professional, hospitalist, and primary care physician are all helpful and can be used to gain insight for risk assessment. Comorbid conditions should be noted.

Current use or previous exposure and response to opioids is also important to document, including a history of chronic opioid efficacy or tolerance, or of opioid-related adverse events. The history should also note chronic use of other sedative medications such as benzodiazepines and muscle relaxants. Risk also depends upon the type of surgery the patient will have and expected intensity and duration of postoperative pain.

Risk assessment is particularly difficult. Even though specific risk factors for OIVI are well described (Table 1), there is not a validated and comprehensive risk scoring system for OIVI in the perioperative setting. Adding to this complexity is that every patient is at risk. Patients who are opioid tolerant are at risk due to the potential difficulty with pain control and the need to escalate dosages. Opioid naïve patients are also at significant risk because of unpredictable responses to the initial dosages.

Table 1: Risk Factors for Opioid-Induced Ventilatory Impairment (OIVI)

| One or more of these risk factors indicate patients are at increased risk: |

| Age >55 |

| Obesity (e.g., body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) |

| Untreated obstructive sleep apnea |

| History of snoring or witnessed apneas |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness |

| Neck circumference ≥44.45 cm |

| Preexisting pulmonary or cardiac disease or dysfunction, e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure |

| Smoker (>20 pack-years) |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists patient status classification 3-5 |

| Concomitant administration of sedating agents, such as benzodiazepines or antihistamines |

| Continuous opioid infusion in opioid-naïve patients, e.g., IV PCA (Patient-Controlled Analgesia) with basal rate |

| First 24 hours of opioid therapy, e.g., first 24 hours after surgery is a high-risk period for surgical patients |

| Prolonged surgery (>2 hours) |

| Thoracic and other large incisions that may interfere with adequate ventilation |

| Large single bolus techniques |

| Naloxone administration: Patients given naloxone are at higher risk for additional episodes of respiratory depression |

| Increased opioid dose requirement: |

| Opioid-naïve patients receiving >10 mg of morphine or equivalent in post anesthesia care unit (PACU) |

| Opioid-tolerant patients who require a significant amount of opioid in addition to their usual daily dosing, e.g., the patient who takes an opioid analgesic before surgery for persistent pain and received several IV opioid bolus doses in the PACU followed by high-dose IV PCA postoperatively |

| Adapted from Pasero C, McCaffery M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management. St. Louis: Mosby, 2011, p.516. |

The Joint Commission Standards as outlined in the R3 Report require that every patient’s pain treatment is assessed and monitored in terms of both effectiveness and treatment risk. A team-based approach to risk assessment and mitigation should include roles for physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists, and could include alerts and risk scores for the most common and serious risk factors, including patients that are opioid naïve, those with renal failure, co-administration of other sedating medications, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) use, the elderly, and the obese.

Figure 1: STOP-BANG11

|

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) currently has a mentored implementation program to institute hospital-wide risk reduction and patient safety improvement for patients receiving opioids (Reducing Adverse Drug Events due to Opioids or RADEO).6 Experienced mentors are provided by SHM. These quality improvement and pain control experts help coach hospital-based teams to improve the quality and safety of opioid prescribing and administration at their hospitals. This study is evaluating a number of risk assessment strategies and risk mitigation approaches. Among these approaches are preoperative STOP-BANG (Figure 1) screening for obstructive sleep apnea with triage to postoperative continuous positive airway pressure or ventilation monitoring as appropriate. Electronic health record (EHR) alerts based on age and renal failure, and pharmacy screening for specific high-risk patients, medications, or medication combinations are also being evaluated.

At present, there is no single comprehensive strategy that can determine patient risk with OIVI with 100% accuracy. However, based on an analysis of challenges that your institution faces, our recommendation is that all hospitals have a risk assessment and mitigation strategy to decrease OIVI that is team-based, measured, monitored, and adjusted based on your outcomes.

Strategy 2: Prescribing Guidelines and Standards

The Joint Commissions R3 Report requires that hospitals have available non-pharmacologic pain treatment modalities and that pain treatment plans be based on the patient’s history, clinical condition, and the goals of care. In addition, there are other elements that should be considered in developing prescribing practices within an institution.

We suggest the following:

- Clearly identify which clinical provider is responsible for pain management, particularly postoperative pain. Agreement between specialties at a service line level needs to be in place and understood by the patient, nursing staff, and the pharmacy. The clinical provider responsible for pain management may differ based on location in the hospital—i.e., ED (ED physician), PACU (anesthesia professional), ICU (intensivist), and medical/surgical floor (hospitalist or surgeon).

- Standardized handoffs should include all recent (within the last 4 hours, or 24 hours for long-acting or extended-release opioids) opioid dosage administrations.

- The use of standardized order sets that include nonpharmacological and multimodal approaches should be encouraged, or, ideally, required. This is especially important when using PCA. Order sets should comply with up-to-date prescribing safety standards and give clear prescribing instructions and parameters.For example, the maximum dosage with a range should only be two times, and not more than four times the smallest dose, and orders should indicate whether the medication is to be used for mild, moderate, or severe pain. Intervals should be long enough to avoid “dose stacking.” Pharmacists should review and approve all order sets.

- Most hospitalized patients should have a scheduled pain medication if continuous pain is anticipated. Scheduled pain medications are also necessary for patients chronically receiving opioids to avoid opioid withdrawal. Scheduled pain medications can be non-opioid if the patient is not opioid-habituated.

- Every patient with acute pain receiving opioid medications should have an opioid de-escalation strategy in place. Opioid de-escalation can be imbedded in order sets, based on policies and alerts that require daily re-ordering, or based on pharmacist review and recommendations. Opioid orders that are not time limited should be avoided altogether.

Strategy 3: Patient Assessment and Monitoring Standards

Much like risk assessment, there is a lack of clear evidence for optimal monitoring strategies of patients receiving opioids. The Joint Commission standards require the following.1

- Provider access to state-run Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) and Databases.

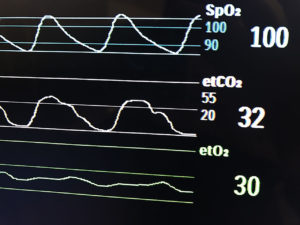

- Access to monitoring devices such as pulse oximetry or capnography as deemed necessary by hospital admistration and medical staff jointly.

- Hospitals have standards for screening, assessing, and reassessing pain that are appropriate for the patient’s age, condition, and cognitive status.

- Each patient’s pain management plan is patient-centered, based on realistic and measurable expectations, based on treatment objectives, and is paired with patient and/or family education.

In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) requires an assessment of risk for postoperative patients receiving IV opioids based on the frequency of dosing, mode of delivery, and duration of IV opioid therapy. In addition, hospitals must address what is to be monitored, how frequently (based on risk), progress towards goals, side effects, and adverse events.7

We recommend a number of best practices:

- Seventy-five percent of the OIVI events occur within the first 24 hours after surgery.8 Consequently, clinicians should especially focus on risk during this time period, including consideration of ventilation monitoring plus pulse oximetry for patients receiving opioids, especially those with, or at risk for, sleep-disordered breathing.

- The APSF suggests using continuous monitoring of oxygenation and ventilation in patients receiving PCA or neuraxial opioids in the postoperative period.9

- The ongoing assessment of pain should not solely be based on numeric (1–10) or subjective (mild, moderate, severe) scales. Pain assessments should include functional criteria that tie to the goals of care for the patient—for example, the ability to mobilize and the ability to sleep. Pain assessments should also be based on nursing judgment as well as patient input and goals of care.

- Every patient receiving opioids should have regular nursing assessments of the level of sedation at appropriate intervals including after dosing of an opioid. Level of sedation should be assessed approximately 15 minutes after dosage of IV opioids, and 30 minutes for PO administration. The most common sedation scale used to assess the sedating effects of opioids is the Pasero Opioid-induced Sedation Scale (POSS).10 POSS is a part of the nursing flow sheet in most EHRs (Figure 2). The sedation scale, pain score, and nursing judgment and observation of functional assessment should be used by nursing to make decisions about administering PRN or scheduled opioids as well as other sedating medications.

- Hospital providers who develop protocols that incorporate continuous monitoring with oximetry and capnography should recognize the benefits and limitations of these monitors and recognize the real dangers of alarm fatigue and the difficulty of setting alarm thresholds that are clinically meaningful.

Figure 2: Pasero Opioid-induced Sedation Scale (POSS)

| S | = Sleep, easy to arouse Acceptable; no action required; may increase opioid dose as indicated. |

Adapted from Pacero C. Acute pain service policy and procedure manual, Los Angeles: CA, Academy Medical Systems; 1994. |

|

Strategy 4: Engaging the Medical Staff

Institutional support is critical to the success of any process or practice in your hospital, including implementing The Joint Commission’s opioid safety standards. Support must occur at all levels. An executive sponsor for an “opioid safe practices committee” should help establish governance and develop a project charter that is aligned with the mission and vision of the hospital. In addition, the executive sponsor is essential in garnering necessary resources such as a project budget, purchasing capital, project management, dedicated clinician time, clerical support, and providing information technology (IT), data collection, and data analysis personnel.

Changes in clinical practice should be designed by front-line clinical staff and facilitated by medical staff leadership and administration. This is best achieved via a multidisciplinary committee involving physicians from different specialties, nursing, quality improvement staff, pharmacy, and IT personnel. In addition, The Joint Commission requires that the medical staff are involved in an ongoing quality improvement effort, including establishing metrics and analyzing data.

It is our opinion that a respected physician champion is critical for success. This physician can lead your committee and be the face of this effort to the medical staff.

An important role of this champion or other physician leaders is medical staff education which can occur via grand rounds or other methods that are effective in your hospital. Ideally this champion will also have the political savvy to help get support for needed changes.

Some further keys to engaging your medical staff are

- Have a statement of purpose. It should be brief, coherent, and easily understood by interested parties. The statement of purpose explains why the opioid safety efforts are valuable to your hospital. An example of such a statement would be, “In 2019 and thereafter in our hospital we will have no serious adverse events related to opioids.”

- Recognize that not everyone will initially be on board with the opioid safety program. Anticipate concerns and provide answers. Help everyone see the value in this work. Tactics include both sharing data and patient safety stories. Get everyone to understand that their commitment really matters to patient care.

- Identify key stakeholders and involve them early and gain their support. These are the individuals that will be needed in order to ensure the success of the project and also motivate and engage others. They will also provide valuable feedback and help formulate strategies for needed change.

- Measure your baseline performance and set achievable and measurable objectives. Develop a scorecard to evaluate progress. Data should be transparent and reported broadly.

- Develop a trusting environment. One key is not asking staff to increase their workload in order to participate on the project.

- Focus on change management, keeping in mind that changes are easier when they are imbedded in existing clinical workflows. In addition, data collection can be taxing—when designing interventions that will be measured, keep in mind the time associated with data collection.

Conclusion

OIVI leading to respiratory failure and death is preventable. Opioid-related adverse events provide opportunities to reflect on current practices and institute systems and behavioral changes that will improve outcomes and produce safer patient care. The Joint Commission R3 report and associated standards require all accredited hospitals to have a comprehensive opioid prescribing and administration safety plan. We recommend that hospital administration and medical staff leadership embrace these standards, not simply to be in compliance, but as an opportunity to improve the safety of opioid prescribing and administration within the hospital and reduce the risk of OIVI.

Dr. Frederickson is Medical Director of Hospital Medicine at CHI Health in Omaha, NE, and an Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine at the Creighton University School of Medicine.

Dr. Lambrecht is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Creighton University School of Medicine and a staff hospitalist at CHI Health Creighton University Medical Center–Bergan Mercy.

Both authors have no disclosures to report.

References

- Guidelines: Joint Commission enhances pain assessment and management requirements for accredited hospitals. The Joint Commission Perspectives 2017;37:1-4. Available at https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/Joint_Commission_Enhances_Pain_Assessment_and_Management_Requirements_for_Accredited_Hospitals1.PDF Accessed March 2018.

- Davies EC, Green CF, Taylor S, et al. Adverse drug reactions in hospital in-patients: A prospective analysis of 3695 patient-episodes. PLoS One 2009;4:

E4439. - Dahan A, Aarts L, Smith TW. Incidence, reversal, and prevention of opioid-induced respiratory depression. Anesthesiology 2010;112:226–238.

- Association for the advancement of medical instrumentation. Infusing patients safely: priority issues from the AAMI/FDA Infusion Device Summit. 2010;1–39.

- Reed K, May R. HealthGrades patient safety in American hospitals study. HealthGrades March 2011;5:1–34.

- www.hospitalmedicine.org/clinical-topics/opioid-safety/. Accessed March 2018.

- Center for Clinical Standards and Quality/Survey & Certification Group. Memorandum for requirements for hospital medication administration, particularly intravenous (IV) medications and postoperative care of patients receiving IV opioids. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. March 14, 2014. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-14-15.pdf. Accessed March, 2018.

- Jungquist CR, Smith K, Nicely KLW, et al. Monitoring hospitalized adult patients for opioid-induced sedation and respiratory depression. Am J Nurs 2017;117: S27–S35.

- Weinger MB, Lee LA. No patient shall be harmed by opioid-induced respiratory depression. APSF Newsletter 2011:26:21–40. https://www.apsf.org/newsletters/html/2011/fall/01_opioid.htm

- Pasero Opioid-Induced Sedation Scale (POSS) [Online]. Available: https://www.ihatoday.org/uploadDocs/1/paseroopioidscale.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2015.

- Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang Questionnaire: a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2016;149:631–8.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF