We oppose the reliance on color-coded syringe labels because we feel that the colors provide a false reassurance of the content of the syringe, decreasing the chance that anesthesia professionals will read the labels as carefully as they should. As early as 2008, in an APSF newsletter,6 Dr. Workhoven emphasized that anesthesia professionals do not always read the label because they think that they have time only to recognize the color, shape, or size of the intended drug or syringe. We are now ten years later, and must demand better than our reliance on recognition of colors to keep our patients safe.

Related Article:

PRO: Color-Coded Medication Labels Improve Patient Safety

CON: Anesthesia Drugs Should NOT Be Color-Coded

Color-coding is the systematic, standard application of color to aid in classification and identification. A color-coding system allows people to memorize a color and match it to its function. Color-coding of anesthesia drug labels has been viewed by practitioners as a common-sense approach, and has been promoted by standards created by the American Society of Anesthesiologists1 and the American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM).2 Although color-coding has never been shown to reduce the incidence of medication errors in the operating room (OR), it may mitigate their harm because if there is an accidental syringe swap of medications in the same general class (e.g., opioid for opioid), the adverse effect of the swap may not be as clinically meaningful as a swap with a drug from another class (e.g., neuromuscular blocker).

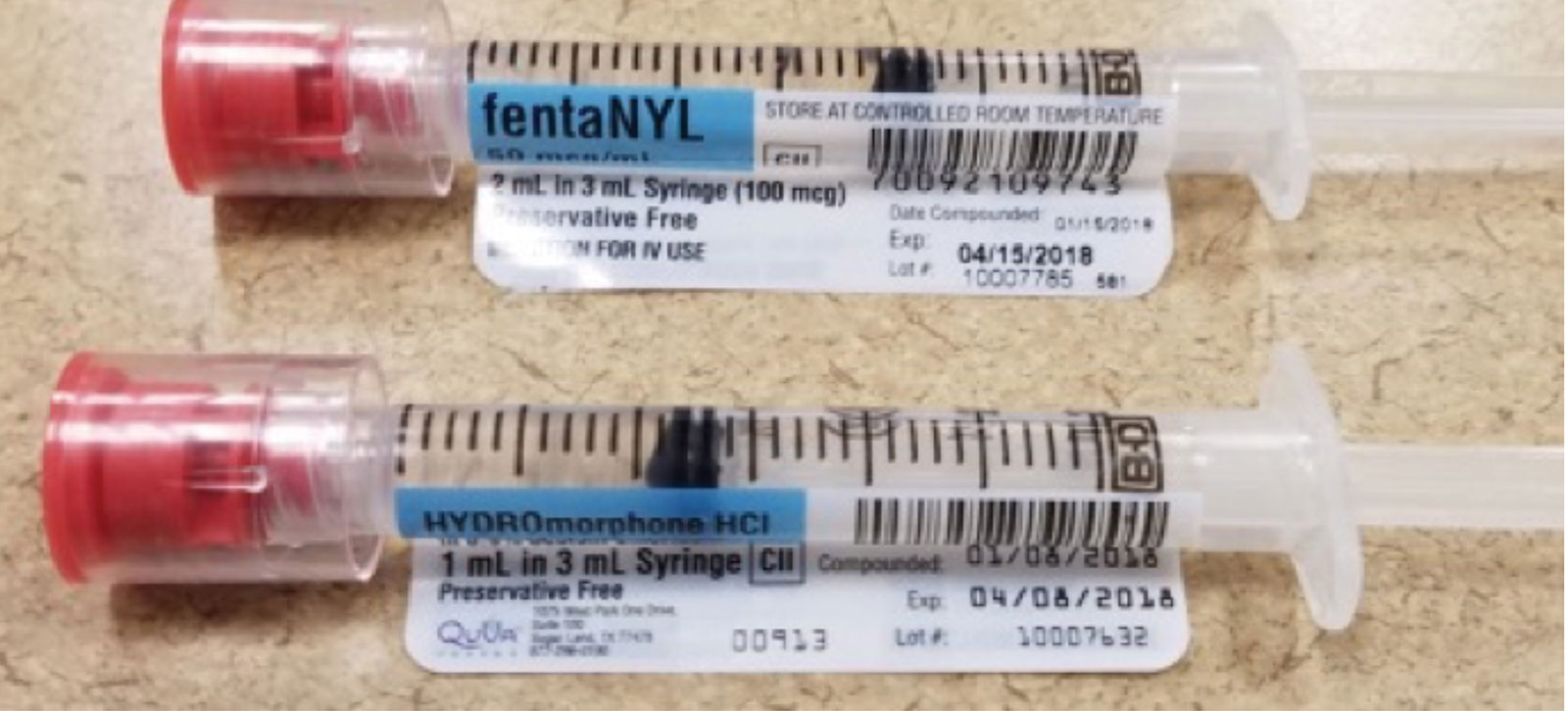

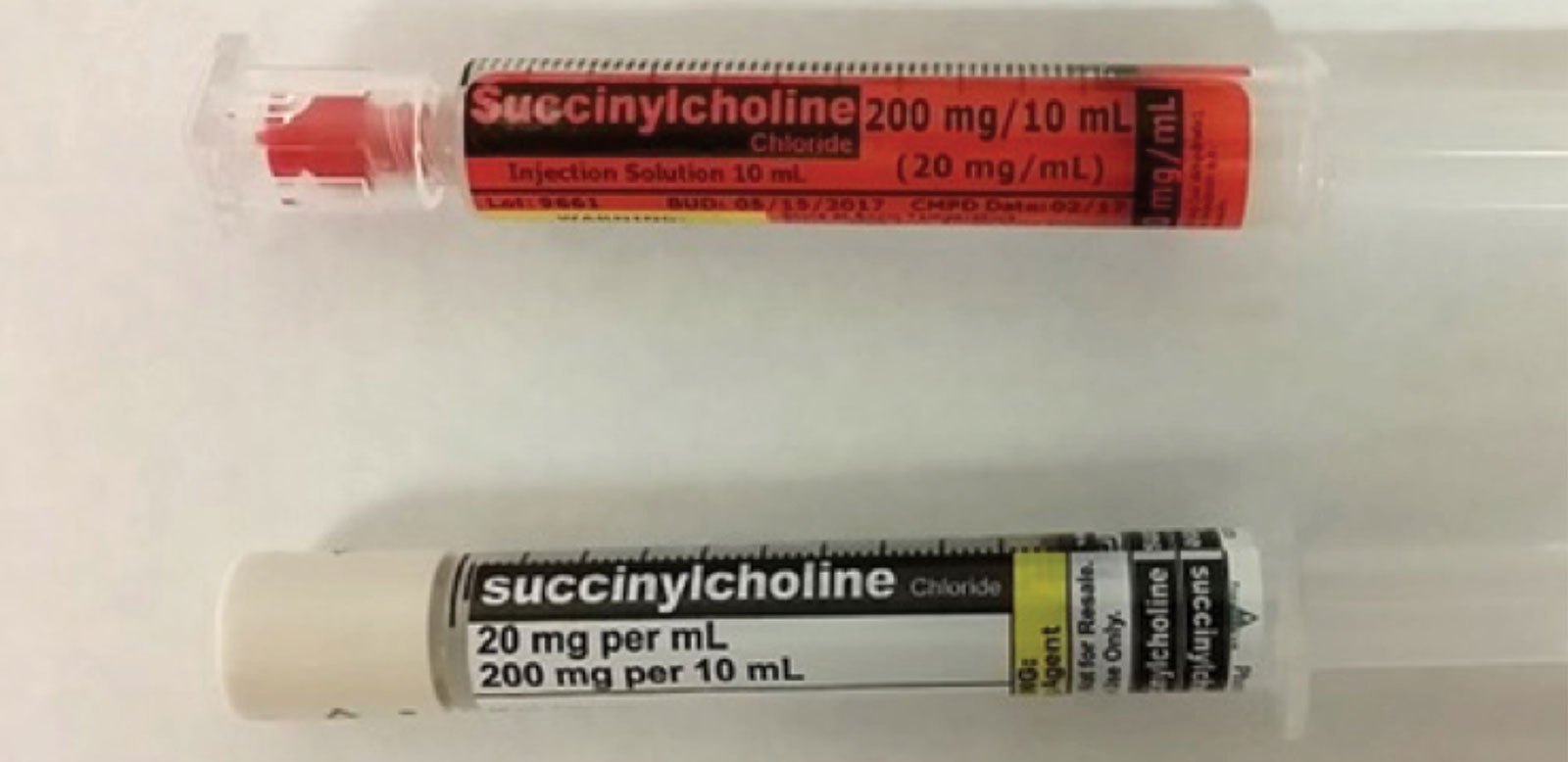

If color-coding makes intuitive sense, why do the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), American Medical Association (AMA), and the American Society for Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) all oppose it? First, color-coding is difficult to maintain, especially when syringes are increasingly being prefilled and prelabeled by a combination of in-house pharmacies and non-hospital-based outsourcers, and then used throughout many parts of the hospital. For example, at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, prefilled anesthesia syringes made by an automated robot are supplied with a white label with black letters (Figure 1), and those made by outsourcers may contain differently colored labels because no standardization for color-coding exists (Figure 2). If one relied on color-coding to pick the correct medication each and every time, accidental administration of the wrong medication is inevitable. This was illustrated in a recent case report from the Anesthesia Incident Reporting System, which described what happened when an in-hospital pharmacy took over production of prefilled hydromorphone syringes when their outsourcer had an acute shortage. The new syringes did not contain the usual blue opioid labels and were confused with dexmedetomidine, which was accidentally administered by anesthesia professionals on at least three occasions.3 In addition, there’s a limit to the variety of discernible colors available for commercial use. Subtle distinctions in color are poorly discernible unless products are adjacent to each other.4,5 The more colors that are used, the greater the risk of confusing a color and its meaning. Clinicians who are color-blind may misidentify color-coded products, leading to a medication error. Relying on color-classification systems as the primary way to identify a drug risks bypassing the recommended three readings of the drug label (Table 1).

Figure 1. Medication syringes with white label and black letters prepared by hospital pharmacy. Anesthesia professional must have put on an additional colored label.

Figure 2. Medication syringes prepared by outsourcers may have different colored labels depending on manufacturer.

Table 1. Three Recommended Readings of the Drug Label

|

|

|

The OR environment is unique with regard to drug preparation. When anesthesia professionals prepare drugs in the OR, they retrieve the medication vial or ampule from a cart, draw up the medication into a syringe, and apply a color-coded adhesive label to the syringe. For most patients, only a single agent within each drug class is prepared. Thus, each drug has its own color, and anesthesia professionals typically know what is in each syringe because they personally prepared it. However, preparing medications at the point of care (i.e., the OR) is an inherently risky endeavor for many reasons, including, but not limited to: unintentional vial swap, accidental failure to label the final medication syringe, and possible contamination of the drug due to preparation in an unsterile environment.

We believe that the future of medication safety in the OR includes the prefilling and prelabeling of medications prior to arrival in the OR. This can be accomplished by an in-house hospital pharmacy, an outsourcing drug distributor, and/or the drug manufacturer. These prefilled syringes, although possibly color-coded by class, could increase the risk of syringe swap because they were not directly prepared by the anesthesia professional, especially if provided in similar-sized syringes and similar labeling formats. For example, it’s possible to have three drugs—morphine, fentaNYL, and HYDROmorphone—each with significant potency variations, all in blue labeled syringes in the same physical area. A mix-up of any one of these drugs can cause serious harm to the patient, such as unanticipated respiratory depression leading to anoxia.

With drug shortages impacting anesthesia practices, it would also be possible for one concentration of a medication (e.g., morphine 1 mg/mL) to be mixed-up with another concentration of that medication (e.g., morphine 10 mg/mL), yet both would employ the same color scheme. Of course, it is always possible that the hospital pharmacy or outsourcer may accidentally swap medications or labels, but this is much less common because their drug preparation spaces are segregated, as opposed to the OR environment where all drugs coexist in the same physical space.

Finally, these commercially prepared prelabeled syringes may be used in non-OR environments in the hospital by administering nurses or other providers that may not be as familiar with the standard anesthesia colors, which could result in an accidental syringe swap. Within the OR, patients are carefully monitored, and immediate care is available in case of a medication mix-up. Outside the OR, mix-ups can often be difficult to recognize and manage quickly in non-monitored areas; or an error can go unrecognized if syringes are accidentally returned to the wrong storage area or if they are placed on a table with other syringes of drugs in the same class.

The most practical solution to offset the disadvantages of color-coding while enhancing safety is to adopt a technological strategy, such as bar-code scanning (or any similar future technology) of syringe labels to catch inadvertent syringe swaps, thus assuring clinicians that they are administering the correct drug. In essence, color-coding relies on human skills, which are indisputably unreliable.

In summary, we oppose the reliance on color-coded syringe labels because we feel that the colors provide a false reassurance of the content of the syringe, decreasing the chance that anesthesia professionals will read the labels as carefully as they should. As early as 2008, in an APSF Newsletter,6 Dr. Workhoven emphasized that anesthesia professionals do not always read the label because they think that they have time only to recognize the color, shape, or size of the intended drug or syringe. We are now ten years later, and must demand better than our reliance on recognition of colors to keep our patients safe.

Matthew Grissinger RPh, FISMP, FASCP, is director of Error Reporting Programs, Institute for Safe Medication Practices.

Dr. Litman, DO, ML, is medical director of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices and professor of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and an attending anesthesiologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Statement on creating labels of pharmaceuticals for use in anesthesiology. 2015; http://www.asahq.org/~/media/sites/asahq/files/public/resources/standards-guidelines/statement-on-labeling-of-pharmaceuticals-for-use-in-anesthesiology.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- ASTM, Standard specification for user applied drug labels in anesthesiology. 2017; https://www.astm.org/Standards/D4774.htm. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- A case report from the Anesthesia Quality Institute, 2018; https://www.aqihq.org/files/AIRS_6.18.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- Christ RE. Review and analysis of color-coding research for visual displays. Human Factors. 1975;17:542–570. web.engr.oregonstate.edu/~pancake/cs552/guidelines/color.coding.html. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- American National Standards Institute, Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation. Human factors engineering guidelines and preferred practices for the design of medical devices (ANSI/AAMI HE-48). Arlington, VA: Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, 1993; pg. 41.

- Workhoven M. There is no substitute for reading the label. APSF Newsletter. 2008;23:19. https://www.apsf.org/article/there-is-no-substitute-for-reading-the-label/. Accessed December 10, 2018.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF