Multidisciplinary obstetric disaster preparedness is essential for all institutions. Obstetric and neonatal patients are unique and require individual consideration. Disaster planning, including incorporation of OB TRAIN and other obstetric-specific tools, awareness of local maternity hospital’s levels of care, healthcare provider training, and knowledge of local resources will help provide optimal patient care in the event of any disaster situation.

Key Points

- Obstetric healthcare providers and facilities that provide maternity care offer services to a population that has many unique features warranting additional consideration.1

- Compared with other patient cohorts, pregnant women, unborn infants and neonates are more vulnerable to acute and long-term effects from disasters.

- An obstetric-specific triage tool and stratification of maternity hospital’s levels of care should enable safe and rapid evacuation and transfer of patients.

- Disaster preparedness and regular training of staff are necessary to assure and facilitate a seamless process during an event

Introduction

Obstetric health care professionals and facilities that provide maternity care offer services to a population that has many unique features warranting additional consideration.1 Compared with other patient cohorts, pregnant women, unborn infants, and neonates are more vulnerable to acute and long-term effects from disasters , both natural (e.g., earthquakes, hurricanes) and man-made (e.g., terrorism). An obstetric-specific triage tool and stratification of maternity hospital’s levels of care should enable safe and rapid evacuation and transfer of patients. Disaster preparedness and regular training of staff are necessary to assure and facilitate a seamless process during an event.

Obstetric health care professionals and facilities that provide maternity care offer services to a population that has many unique features warranting additional consideration.1 Compared with other patient cohorts, pregnant women, unborn infants, and neonates are more vulnerable to acute and long-term effects from disasters , both natural (e.g., earthquakes, hurricanes) and man-made (e.g., terrorism). An obstetric-specific triage tool and stratification of maternity hospital’s levels of care should enable safe and rapid evacuation and transfer of patients. Disaster preparedness and regular training of staff are necessary to assure and facilitate a seamless process during an event.

Disaster Planning for Obstetrics is Unique

Pregnant and peripartum women are unique patient cohorts with specific needs, the majority of which are not encompassed in a generic disaster plan. The key to a successful outcome is including these unique requirements in any preplanning and training, thereby ensuring a rapid response and recovery. The plan needs to provide care for the broad range of acuity levels seen in obstetric patients, from a laboring patient, to a patient who had a normal vaginal delivery, and to a patient who is undergoing emergency cesarean delivery with neuraxial or general anesthesia. Caring for both the mother and fetus/infant with varying levels of acuity is an added challenge which must be considered when/if evacuation is required. Vital to the plan is a system in place that will assure an obstetrical patient is evacuated to the facility best equipped to care for her and her fetus/infant. To accomplish this, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine published a consensus describing levels of maternal care hospitals.2 Obstetric disaster planning needs to be multidisciplinary with involvement from: the obstetric team; anesthesiology team; neonatology team; labor and delivery nursing team; labor and delivery management team; and office of emergency management (if applicable).

Anesthesiology Involvement in Obstetric Disaster Planning

The anesthesiology team can contribute to disaster planning and preparedness by providing specialized knowledge related to ongoing care and observation of patients who have received neuraxial analgesia for labor or surgical anesthesia (neuraxial or general anesthesia); airway equipment; monitoring requirements for specific patient groups (e.g., patients with cardiac or respiratory disease); and safe transportation of all patient groups.

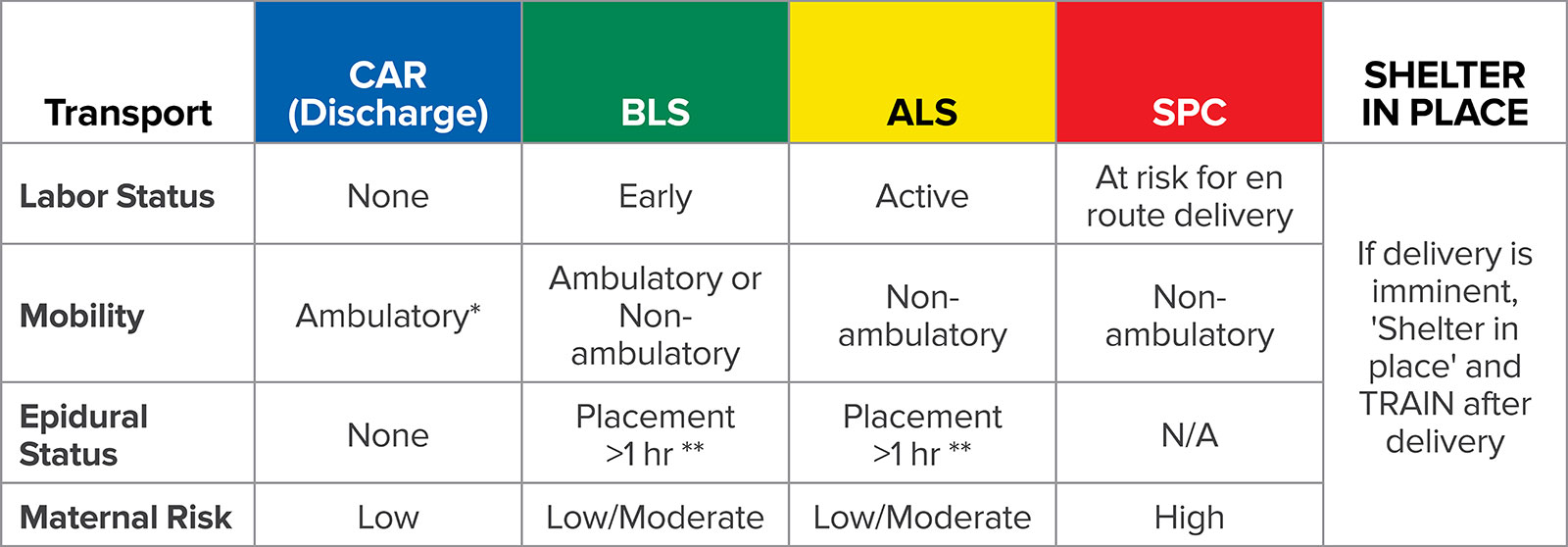

The time elapsed since neuraxial labor analgesia placement is a major consideration when determining the OB TRAIN (Obstetric Triage by Resource Allocation for Inpatient) status of the patient, which determines the most appropriate mode of transportation for the patient in the event of evacuation (Figures 1a and 1b). A period of one-hour following neuraxial block placement was identified as a limiting factor for triage group allocation, as the majority of complications/side effects and drug-related etiologies (e.g., local anesthestic systemic toxicity, anaphylaxis) will usually have occurred during this time-frame.3 In the event of evacuation, labor epidural infusions should be discontinued and the epidural catheter capped to decrease the acuity-level for the mode of transportation required. Alternative modes of analgesia can be offered to patients prior to re-dosing of the epidural catheter (if required) at the receiving institution, depending on local protocols. Examples include intravenous fentanyl boluses or intravenous patient-controlled analgesia using remifentanil.

Figure 1a. OB TRAIN Antepartum and Labor

BLS = Basic Life Support (Emergency Medical Technician-staffed ambulance); ALS = Advanced Life Support (Paramedic-staffed ambulance); SPC = Specialized (must be accompanied by MD or Transport Nurse).

*Able to rise from a standing squat.

**Epidural catheter capped off.

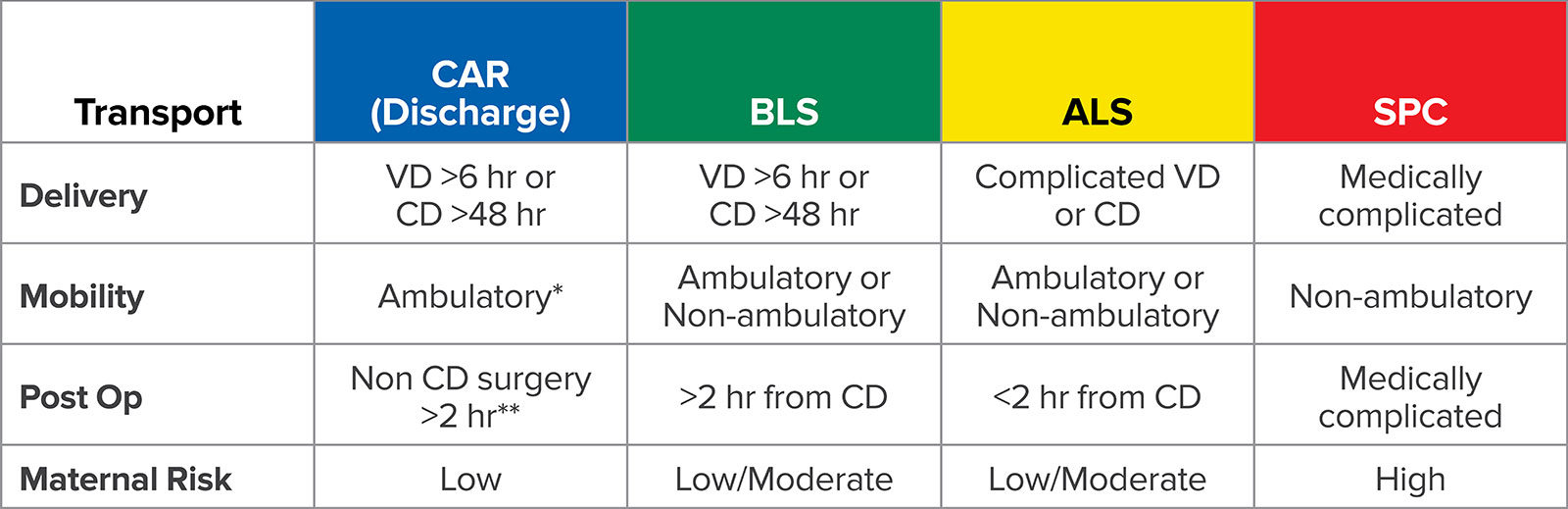

Figure 1b. OB TRAIN Postpartum

BLS = Basic Life Support (Emergency Medical Technician-staffed ambulance); ALS = Advanced Life Support (Paramedic-staffed ambulance); SPC = Specialized (must be accompanied by MD or Transport Nurse); VD = Vaginal delivery; CD = Cesarean delivery.

*Able to rise from a standing squat.

**If adult supervision is available for 24 hours.

Reprinted with permission from the Obstetric Disaster Planning Committee at the Johnson Center for Pregnancy and Newborn Services. Disaster planning for obstetrical services. https://obgyn.stanford.edu/divisions/mfm/disaster-planning.html. Accessed November, 2018.

The anesthesiology team should be prepared to provide clinical care in austere conditions. Airway equipment, anesthesia-related and suction equipment, monitoring modalities, intravenous fluid, and medication supplies all should be available (Table 1 and Figure 2).4

Table 1. Depicts Key Components of an Obstetric Disaster Planning Tool

| Disaster plan tool | Description |

| Disaster plan binder | Each unit should have a designated binder that contains relevant forms and instructions pertinent to the disaster plan. Paper format is recommended in preparation of a power outage or cyber-attack. |

| Disaster box | Equipment specifically designated for use in a disaster should be stored in labeled boxes. The box should be stored in an accessible location in each unit and only retrieved during a disaster. Recommended items include paper forms; flashlights; headlamps; non-rechargeable batteries; handheld doppler transducers; Grab-and-go bags; and vests. |

| Disaster roles | Leadership roles are fundamental in any emergency situation, and should be titled using nomenclature used by the Hospital Incident Command System (HICS) to avoid confusion. The Unit Leader’s role should be assigned to the most knowledgeable individual(s) on the unit. Further roles are the assistant unit leader (obstetric resident and/or team leader nurse), anesthesia professional, triage physician or nurse, bedside nurses, nursing assistants/technicians, and clerk. |

| Job action sheet (JAS) | JASs are role-specific instructions with the purpose to ensure all tasks are completed, ideally within the predetermined time-frames: immediate (operational period 0–2 hr); intermediate (operational period 2–12 hr); and extended (operational period >12 hr, or as otherwise determined by the Hospital Command Center). |

| Obstetric triage | A major step in planning evacuation is patient triage. Vehicle numbers and availability will most likely be limited. The triage system can be used to determine the resources required and the optimal order of evacuation to allow a quick and appropriate evacuation of patients.11 -13 |

| Census worksheet | Mother and infant data sheet containing protected health information such as name, medical record number, date of birth, and also current physical location and planned destination (for tracking). |

| Department damage map | A plan that shows every staff room, patient room, and common area within the unit to identify useable (safe) vs. non-useable areas (unsafe due to debris, flooding, electrical hazard, etc.). |

| Grab-and-go bag | An empty backpack (not pre-filled due to perishable items) containing a list of essential supplies should be available for individualized patient care, including items for an off-site delivery. This individualized Grab-and-go bag will accompany the patient at the time of either shelter-in-place off the unit, or evacuation. (Figure 2). |

| Transfer form | A paper form with pertinent medical information should be available and given to the patient at the time of transfer, allowing optimal patient care to be continued at the receiving hospital. |

| Transfer orders form | Orders specific to maternal and fetal monitoring (if applicable), fasting/nutrition status, medications, and intravenous fluid administration. |

| Medication conversion instructions | Common obstetric medications should be listed with dose conversions from intravenous to intramuscular administration. |

| Regional hospital’s levels of care | A list of regional hospitals should be available documenting essential information such as distance, phone number, maternal level of care, and neonatal level of care, in order to send patients to the proper hospital with the most appropriate level of care and to avoid maternal-neonatal separation. When patients are transferred to other institutions, it is essential to have an effective patient tracking system in place so the sending institution knows where each patient has been admitted to avoid maternal-neonatal separation, follow up with aspects of clinical care, and send test results, etc. |

| Maternal discharge form and checklist for well-baby discharge | List of criteria that need to be met prior to discharge of a well baby. |

| Reprinted with permission from the Obstetric Disaster Planning Committee at the Johnson Center for Pregnancy and Newborn Services. Disaster planning for obstetrical services. https://obgyn.stanford.edu/divisions/mfm/disaster-planning.html. Accessed November, 2018. | |

Figure 2. OB Anesthesiology Grab-and-go Bag List:

| Airway: | Location/Notes | |

| ☐ | Ambu bag x2 | From epidural cart or on wall in LDR hallway |

| ☐ | O2 tank x2 + wrenches | Dirty utility room across from LDR X (Door code xxxx) |

| ☐ | Laryngoscope + Blade x2 | |

| ☐ | ETT x2 | |

| ☐ | NRB mask x3 | |

| ☐ | Oral airways | |

| ☐ | Proseal LMA #3, #4, #5 | |

| ☐ | Bougie | |

| Suction: | ||

| ☐ | Portable Suction machine | Top of code cart (across from LDR X) |

| Monitors: | ||

| ☐ | Propaq + power and monitor cables | Anesth Tech Rm |

| ☐ | Portable SpO2 | Top of OR X Anesthesia machine |

| IV: | ||

| ☐ | IV start equipment | |

| ☐ | Normal saline or lactated ringers 1000 ml bag x4 |

|

| ☐ | IV blood tubing x2 | |

| Meds: | ||

| ☐ | Omnicell Keys

|

|

| ☐ | Propofol + Succinylcholine | |

| ☐ | Labetalol | |

| ☐ | Pitocin | |

| ☐ | PPH Kit x2 | Med room + PACU Omnicells only |

| ☐ | Emergency medications: Epinephrine/ Atropine/ Phenylephrine/ Ephedrine | |

| ☐ | SL NTG | |

| 2% lidocaine/ epinephrine/ bicarbonate 10 ml syringes x2 | ||

| Other: | ||

| ☐ | 10 ml syringe x 20 | |

| ☐ | 18G needle x 20 | |

| ☐ | 25G needle x 10 |

| Gas Shut-Off Valves: Turn off if smoke or fire present, once off, only engineering can turn back on. | |

| PACU/Triage rooms/US room: | Just outside PACU |

| LDR rooms: | Between break room and double doors to OR |

| OR X: | Just outside OR X |

| OR Y: | Just outside OR Y |

| OR Z: | Just outside OR Z |

| Reprinted with permission from the Obstetric Disaster Planning Committee at the Johnson Center for Pregnancy and Newborn Services. Disaster planning for obstetrical services. https://obgyn.stanford.edu/divisions/mfm/disaster-planning.html. Accessed November, 2018. |

|

Multidisciplinary Obstetric Disaster Plan Tools

Institutions should have generic disaster plans established, and in addition should have obstetric-specific tools (Table 1). On-line tools developed to guide hospital-based evacuation or shelter-in-place for obstetric units are available.4

Obstetric Disaster Preparedness Training

Disaster preparedness training can be delivered in various formats, such as: on-line information through government-funded resources; medical and nursing societies; and in some areas, simulation-based multidisciplinary training is available.5-9 Simulation-based training can be organized at the department/institution level, or interagency drills in collaboration with hospitals, emergency services, and disaster organizations on a county level.10

Conclusion

Multidisciplinary obstetric disaster preparedness is essential for all institutions. Obstetric and neonatal patients are unique and require individual consideration. Disaster planning, including incorporation of OB TRAIN and other obstetric-specific tools, awareness of local maternity hospital’s levels of care, health care provider training, and knowledge of local resources will help provide optimal patient care in the event of any disaster situation.

Dr. Abir is currently a clinical associate professor in the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine.

Dr. Daniels is currently a clinical professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Stanford University School of Medicine.

Both authors have no disclosures as they pertain to this article.

References

- Hospital disaster preparedness for obstetricians and facilities providing maternity care. Committee Opinion No. 555. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2013:121:696–99.

- Levels of maternal care. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:502–15.

- Di Gregorio G, Neal JM, Rosenquist RW, Weinberg GL. Clinical presentation of local anesthetic systemic toxicity: A review of published cases, 1979 to 2009. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:181–7.

- Disaster planning for obstetrical services. https://obgyn.stanford.edu/divisions/mfm/disaster-planning.html. Accessed November 2018.

- The Department of Homeland Security. https://www.ready.gov. Accessed April 2018.

- American Red Cross. How to prepare for emergencies. http://www.redcross.org/get-help/how-to-prepare-for-emergencies. Accessed April 2018.

- Disaster Management and Emergency Preparedness. American College of Surgeons. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/education/dmep. Accessed April 2018.

- Center for Domestic Preparedness. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://cdp.dhs.gov. Accessed April 2018.

- National Incident Management System (NIMS). Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/nims/. Accessed April 2018.

- Jung D, Carman M, Aga R, Burnett A. Disaster preparedness in the emergency department using in situ simulation. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2016;38:56–68.

- Daniels K, Oakeson AM, Hilton G. Steps toward a national disaster plan for obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:154-158.

- Cohen RS MB, Ahern T, Hackel A. Disaster planning – triaging resource allocation in neonatology. J Invest Med. 2010;58:188.

- Lin A, Taylor K, Cohen RS. Triage by resource allocation for inpatients: a novel disaster triage tool for hospitalized pediatric patients. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2018;31:1–5. [Epub ahead of print].

The information provided is for safety-related educational purposes only and does not constitute medical or legal advice. Individual or group responses are only commentary, provided for purposes of education or discussion, and are neither statements of advice nor the opinions of APSF. It is not the intention of APSF to provide specific medical or legal advice or to endorse any specific views or recommendations in response to the inquiries posted. In no event shall APSF be responsible or liable, directly or indirectly, for any damage or loss caused or alleged to be caused by or in connection with the reliance on any such information.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF