Although it has been nearly twenty years since the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s landmark publication “To Err is Human,” medical errors continue to be a leading cause of patient morbidity and mortality.1 Studies have estimated human error accounts for 87% of all medical errors1,2 with varying prevalence stratified by specialty and clinical situation (lower than 5% in radiology to as high as 10–15% associated with emergency medicine care).2,3 In anesthesia, human errors have been shown to account for up to 83% of errors, with fixation errors among the major culprits.2-4 The reasons for why human errors continue to be prevalent are varied, but include the complexity of the OR environment, the acuity of crisis situations, and psychophysiologic variables that are unique to individuals and teams.2-4

Fixation errors are a type of cognitive error in which individuals and teams focus on one aspect of a situation, while ignoring more relevant information.3-7 These errors have been categorized into three different types: a) “this and only this” errors occur when only one diagnosis or solution to a problem is considered, b) “everything but this” errors occur when the correct diagnosis or solution is not considered, and c) “everything is okay” errors occur when a problem is not acknowledged.4,6 Cases 1 and 2 (Figures A & B) typify perioperative care situations where different types of fixation errors occurred. These events galvanized health care professionals from our institution to embark upon a patient safety transformation, which has led to the publication of an innovative educational tool. This teaching instrument consists of a hybrid book, entitled Ok to Proceed? What every health care provider should know about patient safety, which blends printed text with multimedia, and reviews a variety of patient safety topics, including fixation errors.6 In this article, we focus on fixation errors and detail why innovative strategies for addressing them are so important to patient safety.

Case 1:

An eight-year old boy who underwent appendectomy.

Soon after the procedure, he suffered a surgical complication that required parenteral nutrition. A series of errors led to the preparation of a mixture containing ten times the prescribed potassium concentration, and the patient suffered a cardiac arrest. Vigorous resuscitation efforts failed.

Figure A. A nurse checking the IV line after beginning transfusion of an IV fluid. However, the child is accidentally given a preparation containing ten times the prescribed potassium concentration.

Reproduced and modified with permission from authors and the Boston Medical Center.

Evaluation:

The health care team suffered an “everything but this” fixation error by failing to consider hyperkalemia as a cause of the patient’s cardiac arrest.

Case 2:

A healthy middle-aged man presented for oral surgery.

This patient required nasotracheal intubation for the procedure. After the laryngoscopist advanced the tube into the trachea under direct visualization, it was difficult to ventilate the lungs. The team believed that the reason for airway resistance was bronchospasm. Fixated on this diagnosis, the team did not entertain the possibility that the tube could have been kinked within the trachea or other causes of an inability to adequately ventilate. The patient died due to anoxia.

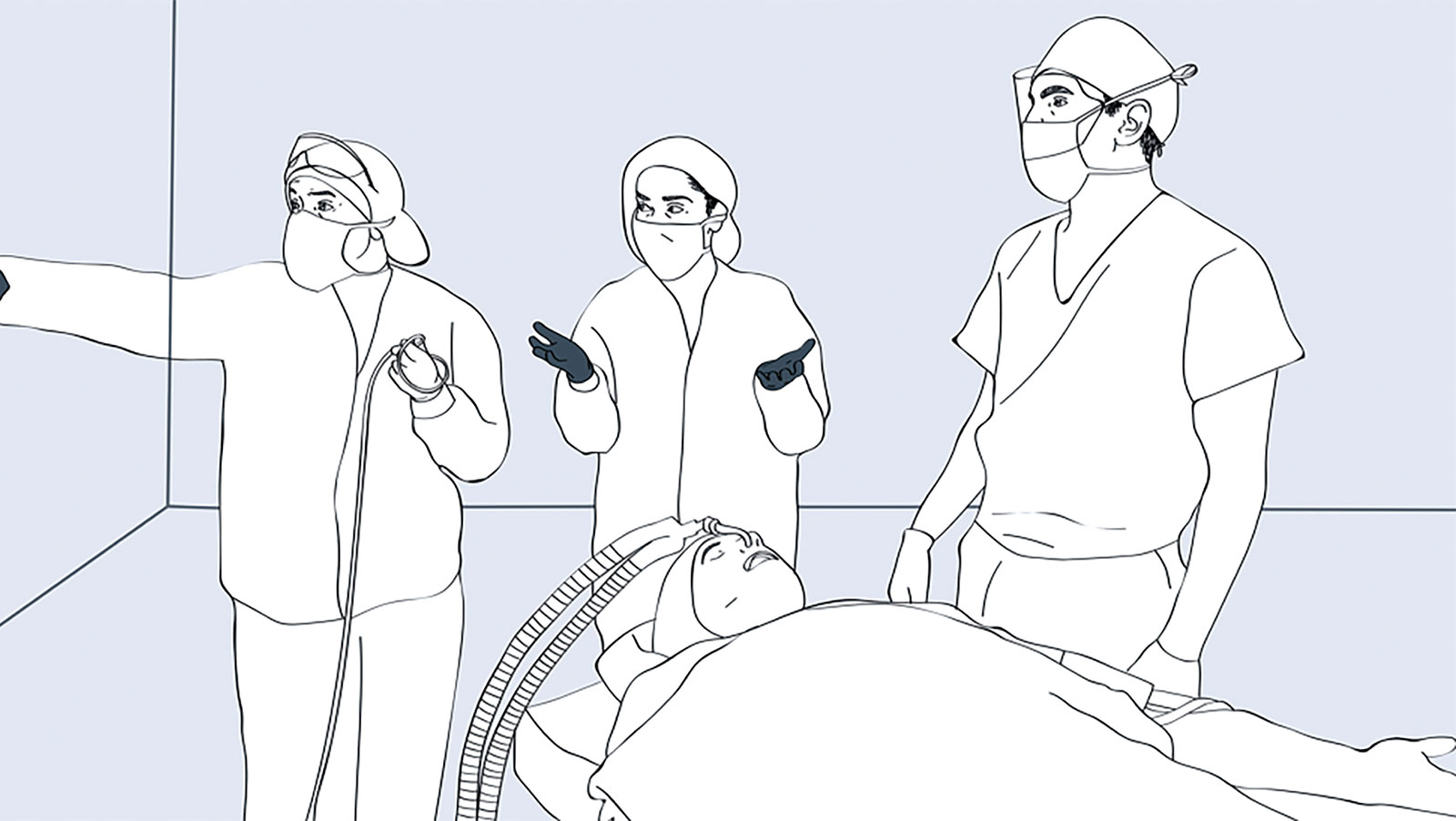

Figure B. OR team fixated on bronchospasm as the cause of airway resistance after a nasotracheal intubation.

Reproduced and modified with permission from authors and the Boston Medical Center.

Evaluation:

The OR team was victim to a “this and only this” fixation error when they concluded that bronchospasm was causing the airway resistance.

Fixation errors have also been called “anchoring” errors or “tunnel vision”2,4,5,7 and can be broadly considered as human errors of insight. For this reason, much of the research about fixation errors has been in the fields of cognitive psychology and aviation safety.4,5 The work of Fioratou and colleagues elucidate how experience and knowledge work against us and can result in fixation errors.5 In medicine, as in other fields, we rely on our prior experience to help us approach new situations; this is known as heuristic or experiential learning. In the case of fixation errors, our experiences bias us to the new situation, making us cling to a conclusion even when presented with information to the contrary.3-7,9 It is as if we anchor to an idea. The reasons for this are varied but include availability bias (tendency to overvalue examples that come easily to mind), prior experience, mental shortcuts, and the high cognitive load of complex environments (e.g., operating room).1,4

It is difficult for both trainees and seasoned anesthesia professionals to identify and then rectify a fixation error due to the focus on heuristic training. Thus, it is very important to encourage learning tools that teach “outside-the-box” or “lateral” thinking, which have been shown to circumvent fixation errors.5,9-10 The most important strategy for overcoming fixation errors is awareness.5,9,10 This is promoted by articles such as this one, patient safety learning material, didactics, and simulations.9 Individuals must be made aware of what fixation errors are, led through exercises where fixation errors have occurred, and work through these errors in simulations. Through exposure, trainees and professionals alike are taught that shortcuts and obvious conclusions can be pitfalls leading to fixation errors.5 Therefore, they must employ strategies that may help to mitigate these errors. These strategies are included in Table 1.5,9–11

Table 1. Strategies for Overcoming Fixation Errors

| Rule out the worst-case scenario |

| Accept that the first assumption may be wrong |

| Consider artifacts as the last explanation for a problem |

| Do not bias team members with a previous conclusion |

Obtain a Second Opinion

In making fixation errors, goal-directed behavior is curtailed.5 In these cases, even trial and error procedures can yield useful information5 and participants should consider not repeating the same actions if they yield the same results. Rather, they should entertain the possibility of a fixation error, and change their strategy, particularly in the face of unfavorable results.

Preventing medical errors requires thinking beyond the field of health care and promoting novel educational and cognitive strategies which counteract cognitive errors to create high accountability networks.3,7,12 Our institution is using this approach and creating patient safety initiatives using the book as an innovative alternative to address these complex challenges. This teaching tool capitalizes on the power of storytelling, multimedia, diagrams and digital animation, and is based on real medical errors, engaging players at all levels of health care. Lastly, we are committed to studying the impact of these tools on provider understanding of patient safety issues and, ultimately, their performance.

Dr. Rafael Ortega is professor of anesthesiology, interim chair, and dean of Diversity and Inclusion at Boston University School of Medicine. He has no financial disclosures.

Kunwal Nasrullah is a medical student at Boston University School of Medicine and has no financial disclosures.

References

- Walsh T, Beatty PCW. Human factors error and patient monitoring. Physiological Measurement. 2002;23:111–132.

- Saposnik G, Redermeier D, Ruff CC, et al. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2016;16:138.

- Stiegler MP, Neelankavil JP, Canales C, et al. Cognitive errors detected in anaesthesiolgy: a literature review and pilot study. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2012;108:229–235.

- Chandran R, DeSousa KA. Human factors in anaesthetic crisis. World Journal of Anesthesiology. 2014;3:203–212.

- Fioratou E, Flin R, Glavin R. No simple fix for fixation errors: cognitive processes and their clinical applications. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:61–69.

- Ortega R. Fixation errors. In: Lewis K, Canelli C, Ortega R, eds. OK to proceed? What every health care provider should know about patient safety. 1st ed. Boston, MA: Boston Medical Center. 2018:64–69.

- Arnstein F. Catalogue of human error. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1997;79:645–656.

- Lewis K, Canelli C, Ortega R, eds. OK to proceed? What every health care provider should know about patient safety. 1st ed. Boston, MA: Boston Medical Center; 2018.

- Brindley PG. Patient safety and acute care medicine: lessons for the future, insights from the past. Critical Care. 2010;14:217.

- Carne B, Kennedy M, Gray T. Review Article: Crisis resource management in emergency medicine. Emergency Medicine Australia. 2012;24:7–13.

- Rall M, Gaba DM. Human performance and patient safety. In: Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, et al., eds. Miller’s Anesthesia. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingston; 2010:93–149.

- Stiegler MP, Tung A. Cognitive processes in anesthesiology decision making. Anesthesiology. 2013;120:304–17.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF