To the Editor

A 68-year-old male was scheduled for a right knee arthroplasty after a previous distal femoral replacement became dislocated. Standard ASA monitors where placed and induction was performed with propofol and succinylcholine. The patient was successfully intubated with a Glidescope®, and the endotracheal tube was visualized entering the glottis. The endotracheal tube was connected to the anesthesia circuit and mechanical ventilation was initiated, but the patient rapidly became difficult to ventilate. The SpO2 decreased to the 88-90% range with a positive end-tidal CO2 tracing on the anesthesia monitor. Upon auscultation, bilateral breath sounds were audible, but significant wheezing was present. Heart rate and blood pressure were not significantly altered from preoperative values. With elevated peak airway pressures, bronchospasm was presumed and the patient was treated with nebulized albuterol as the anesthetic level was deepened. The airway was quickly inspected with a fiberoptic bronchoscope and no foreign bodies or mucous plugs were identified. The wheezing, difficult ventilation, and decreased oxygen saturations persisted. After exhausting the alternatives, the breathing circuit was exchanged for a new circuit and almost immediately, the patient became easier to ventilate, the wheezing ceased, and the oxygen saturations improved to 99%.

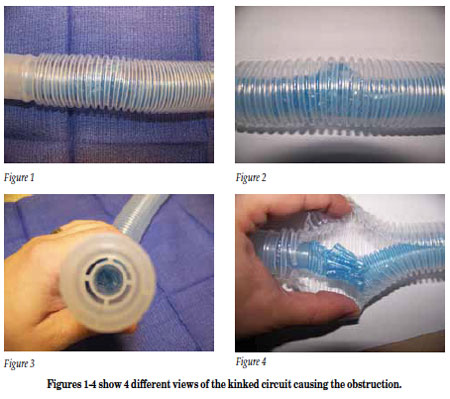

Upon close visual inspection of the equipment, a kink was noted in the inspiratory limb of the coaxial circuit, Figures 1-4. The kink allowed ventilation to occur against moderate resistance at higher than normal pressure, but it was not severe enough to completely occlude gas flow. The partial blockage not only slipped through the earlier equipment check, but it delayed the response to switching to an ambu bag as an alternate method of emergency ventilation. If the kink had caused complete obstruction, and total flow had been occluded, the circuit would likely have been suspected as the cause sooner, and an alternate method of ventilation sought. The circuit, in its damaged state, did not trigger any alarm during the automated anesthesia machine check-out of the Datex Ohmeda Aisys machine prior to the case start. After this incident, the breathing circuit involved was placed on 2 additional anesthesia machines, where it failed to trigger an alarm during the automated check-out process. In the pre-anesthetic visual inspection of the machine and equipment, it appeared to be a functional circuit.

Per hospital policy, a safety report was filed and both the manufacturer and the FDA were informed. The malfunction was later confirmed by the manufacturer of the breathing circuit. The problem was isolated to a faulty adaptor that prevented the full rotation of the inner tube during assembly, and instead, the tube folded on itself. The manufacturer has since implemented a 100% light-box inspection of each circuit after final assembly.

Kinking of the inner tubing of a Bain coaxial circuit has been previously reported.1,2 Several interventions and techniques have been developed to minimize its occurrence. In this case, the inner tubing of the coaxial cable kinked despite the fact that it was corrugated. Several maneuvers have been described for ensuring the patency of the inspiratory limb,3-5 but none of them are fool-proof. Additionally, if not performed carefully, they have the potential to damage the circuit or the machine.6

This case has also demonstrated to us the role that cognitive errors play in critical scenarios.7 We believe that availability bias (choosing a diagnosis because it is frequently encountered) and representativeness (failure to consider circuit malfunction, because circuit malfunction typically presents with complete obstruction) played a role in the delayed diagnosis of the circuit as the cause of the difficulty ventilating this patient. Since circuit malfunctions are a rare event and the machine passed the automated safety check at the start of the case, we did not consider a malfunctioning breathing circuit to be high on our list of differential diagnoses. This was combined with the fact that only a partial occlusion was present, which did not trigger an immediate “popoff” during inspiration since some flow occurred through the circuit. This case serves as a reminder that even with advancing automation of the anesthesia machine safety check-out, nothing can replace a careful and thorough visual inspection of the equipment before each case.

Jonathan B. Cohen, MD

Moffitt Cancer Center

Tampa, Florida

Tariq Chaudhry, MD

Moffitt Cancer Center

Tampa, Florida

References

- Gooch C, Peutrell J. A faulty Bain circuit. Anaesthesia 2004;59:618.

- Garg R. Kinked inner tube of coaxial Bain circuit—need for corrugated inner tube. J Anesth 2009;23:306.

- Pethick SL. Letter to the editor. Can Anaesth Soc J 1975;22:115.

- Foex P, Crampton Smith A. The Foex-Crampton Smith Manoeuvre. Anaesthesia 1977;32:294.

- Ghani GA. Safety check for the Bain circuit. Can Anaesth Soc J 1984;31:487-8.

- Salt R. A test for co-axial circuits: a warning and a suggestion. Anaesthesia 1977;32:675.

- Groopman J. Medical Dispatches: What’s the trouble? How doctors think. The New Yorker January 29, 2007. pp 34-39.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF