In My Opinion

While attending a national anesthesiology conference 2 years ago, a colleague and his spouse strolled through the exhibit area and stopped at the booth sponsored by a major manufacturer of videolaryngoscopes. Within minutes, his wife—a travel agent by trade—successfully understood and used the videolaryngoscope to intubate the trachea in a mannequin at the booth. In essence, her success rate using a videolaryngoscope was 100%! Indeed, this is the Siren song of the videolaryngoscope—a device so intuitive and powerful that it creates the impression for many medical personnel that tracheal intubation is a straight-forward and easy technical exercise. Perhaps more alarming is that the conclusion of many anesthesia professionals that using a videolaryngoscope is the ultimate “failsafe” intubation technique and that it markedly increases the likelihood of successful endotracheal intubation. However, a careful review of current literature does not fully support this conclusion.

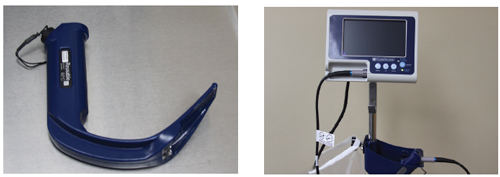

Examples of commercially available videolaryngoscope handle and monitor.

The term “videolaryngoscope” generates 150 Medline citations over the last decade. Only a small number of these publications truly evaluate the efficacy of videolaryngoscopy to improve the ability to successfully intubate the trachea. Many of these studies are performed only on mannequins; whereas, a minority are done in real-life clinical situations in operating theaters, emergency rooms, and other critical care areas. In one of the largest reviews, Aziz et al. evaluated videolaryngoscope use in over 2,000 patients. The 2 institutions that participated in this study used the Glidescope® and the primary outcome was “successful intubation.” They also attempted to define factors that may contribute to failure of the use of the Glidescope®. In their study, the Glidescope® could be used either as the primary method or as rescue for a failed laryngoscopy or fiberoptic intubation. As expected, the use of the Glidescope® was highly successful as a primary method for intubating the trachea and was also very successful, but not quite as frequently as primary use, for rescue of a failed direct laryngoscopy or fiberoptic intubation. In neither the failed direct laryngoscopy group nor the fiberoptic group was the Glidescope® 100% successful in rescuing the airway. Interestingly, when the Glidescope® was used as the primary device and failed, almost 50% of the time the successful rescue method was direct laryngoscopy. Predictors of failure of the Glidescope® included abnormal neck anatomy from surgery, a mass, or history of radiation therapy.1

In a study by Piepho and colleagues, the performance of the Karl Storz C-MAC® videolaryngoscope was assessed after laryngoscopy with a standard American-type MacIntosh adult blade provided only a limited glottic view. As predicted, the C-MAC improved the view in the vast majority but not all patients. Indeed in a minority of patients the glottic view was still inadequate and intubation attempts were not successful with the C-MAC scope. In this study, one patient was rescued using a different blade on the C-MAC scope and the other 2 failures were rescued by direct laryngoscopy using a Miller blade.2

A meta-analysis and review of the Glidescope® was published earlier this year by Griesdale et al.3 In this review, the authors evaluated 17 trials with almost 2,000 patients. They concluded the Glidescope® improved glottic visualization (compared to direct laryngoscopy) in both easy and difficult airways, with a greater relative benefit in the patient with a difficult airway. This review also concludes that there was no difference between the Glidescope® and direct laryngoscopy in terms of successful first attempt intubation or time to intubation except if the laryngoscopist was not an expert.3

Many other publications describe this same pattern of results using videolaryngoscopes. There is usually an improvement of one or more grades in the Cormack-Lehane view of the glottis with videolaryngoscopes, and this often translates into an improvement in the rate of successful oral tracheal intubation. However, no publication documents 100% success with the new videolaryngoscope in terms of improving the glottic view or securing the airway. Thus, it seems prudent—even critical—that anesthesia training programs still prioritize the critical skill of direct laryngoscopy using standard Miller and MacIntosh blades. Moreover, the 2011 edition of the ASA difficult airway algorithm does not use the term videolaryngoscope directly. While there is no doubt that these devices have a vital place in our quiver of airway tools, it is imprudent (or perhaps even counterproductive) to teach and prioritize videoscopy to anesthesiology trainees prior to mastery of standard direct laryngoscopy. Otherwise, we risk endorsing the erroneous concept that the use a videolaryngoscope for every endotracheal intubation is the preferred methodology and a sure pathway to the rescue after one or more failed attempts to secure the airway.

References

- Aziz MF, Healy D, Kheterpal S, et al. Routine clinical practice effectiveness of the Glidescope in difficult airway management: An analysis of 2,004 Glidescope intubations, complications, and failures from two institutions. Anesthesiology 2011;114:34-41.

- Piepho T, Fortmueller K, Heid FM, et al. Performance of the C-MAC videolaryngoscope in patients after a limited glottic view using Macintosh laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia 2011;66:1101-5.

- Griesdale DE, Liu D, McKinney J, Choi PT. Glidescope® videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for endotracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth 2012;59:41-52.

Dr. Allen D. Miranda is an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Dr. Richard C. Prielipp, MD, FCCM, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, and the Chair of the APSF Committee on Education and Training and a member of the APSF Executive Committee.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF