While debate continues over various estimates on the number of medical errors occurring in the United States, there seems to be general consensus that health care is not as safe and reliable as it should be. One of the notable exceptions in recent years is anesthesiology. Improvements made over the past decade have reduced the number of deaths attributed to anesthesia 25-fold from 1 in 10,000 anesthetics to 1 in 250,000 today. As reported in the January 26, 2004, issue of Newsweek, Americans now have 40 million surgical procedures under anesthesia each year, and only about 160 die of anesthesia-related complications.

Yet when those deaths occur, especially in high profile cases such as First Wives Club author, Olivia Goldsmith, who died recently during a cosmetic procedure, the organization and the industry are understandably scrutinized regarding the risks involved with even minor surgery, and involving even a relatively “safe” procedure such as anesthesia.

Strategies for measuring and mitigating risk have received increasing attention in many industries including law enforcement, fire service, and medicine. Since the tragic events of 9/11, America’s efforts toward ensuring homeland security have been strengthened, covering multiple areas, requiring significant resources, and involving far more than the raising or lowering of the nation’s threat level. In aviation, despite a few well-publicized exceptions, the industry has effectively minimized the number of fatal accidents, allowing thousands of daily flights to take-off and land safely without incident.

Health care has gotten a lot of attention lately for mistakes that adversely affect both quality and cost. An item in the Philadelphia Inquirer (2/1/04), reported research from the federal Agency for Health care Research and Quality (AHRQ) finding that US surgical teams leave instruments inside patients 2,700 times per year, creating a total annual cost of $36 million. This is despite the fact that such errors are classified by the National Quality Forum as being among 27 medical events that “should never occur in health care,” and that surgical teams count items (often as many as 200 to 500 per procedure) to ensure they are not left in patients. Even with strong patient safety programs in place, such errors can occur.

There is no “silver bullet” to completely eliminate risk, but there are steps that can be taken to create a culture of safety and develop a high reliability organization (HRO). HROs have been defined as organizations that have been able to consistently reduce the number of expected or “normal” accidents—through culture change, technology, and other means—despite an inherently high-stress, high-tempo environment. Researchers have studied such organizations to uncover best practices that can be more widely applied.

Achieving HRO status in an environment such as health care, which is fairly unpredictable and increasingly complex, is not an easy task. But efforts to nudge the industry in this direction have been mounting, especially since the release of the IOM reports on medical error rates. A wide and growing array of agencies, such as the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation, Leapfrog, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, the National Quality Forum, and the National Patient Safety Foundation, are dedicated in one way or another to the pursuit of quality and risk management in health care.

Among such organizations there is general consensus on the goal to improve safety, yet differences of opinion remain on the precise path to reach that goal. In many cases, traditional methods such as TQM (Total Quality Management), PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) and CQI (Continuous Quality Improvement), have fallen short of their original expectations. Despite an increasing push for accountability and transparency in medicine, errors are difficult to capture and quantify, and can include everything from not following a patient’s dietary guidelines, to mistakes in medication administration or failure to match blood type during a transfusion. Finding a way to improve even a single process within a hospital, however, can yield measurable benefits in terms of both cost and quality.

For example, a recent Six Sigma project that targeted the reduction of bloodstream infections in 1 intensive care unit (ICU) allowed the hospital to exceed CDC guidelines, reduce infection rates by 75%, and generate an estimated $1.2 million per year in savings. There was a statistically significant improvement in 1 SICU, based on approximately 75 central line catheters per month between January and August and an expected 2 infections per month.

Some factors behind the success of this project include the following:

- Clear standard operating procedures were established for each step of the process.

- Audiovisual training in addition to traditional training methods was provided for all staff.

- New barrier precaution kits were assembled.

- Patient satisfaction, literature, and the need to control cost created a common or shared need to drive change.

- Multiple change management tools were used to gain participation and cooperation of nurse and physician staff.

- Recognition of efforts helped build on success and drove the desire to continue the change initiative.

- Continued monitoring and communication of key metrics maintain the results.

- The project team garnered support for the project objectives prior to implementation.

- Precaution kit best practice is being implemented in other departments.

Extrapolating results from a single process improvement effort to develop a HRO is achievable within health care, but requires technical and cultural change management strategies like Six Sigma, Lean, and Work-Out.

What is Six Sigma?

Six Sigma originated in manufacturing in the 1980s and has been described as a measure of quality, a statistical process for continuous improvement, and an enabler for culture change. It is a highly structured method for defining, measuring, eliminating and controlling defects and process variance.

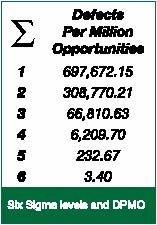

Figure 1. The relationship between Sigma level and the number of defects per million opportunities

Quantitatively, a process performing at Six Sigma will generate fewer than 3.4 defects per million opportunities. As Figure 1 indicates, moving from 3 Sigma to 6 Sigma represents a 20,000 times improvement in quality. Culturally, becoming a Six Sigma organization is like becoming an HRO in the provision of a framework that targets and encourages flawless performance.

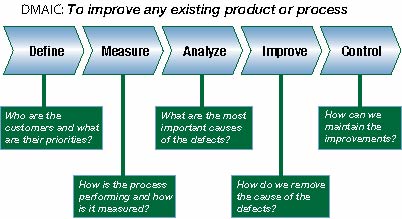

The Six Sigma DMAIC methodology (Define, Measure, Improve, and Control), applies to any existing process with measurable response variables. Figure 2 demonstrates this highly structured, five-phase approach and analytical data analysis. Using DMAIC, a number of hospitals have been able to document impressive benefits. Projects span the organization and have included decreasing patient wait time in the emergency department, optimizing processes surrounding advanced technologies, improving admissions, increasing capacity and access to care, and reducing medication errors.

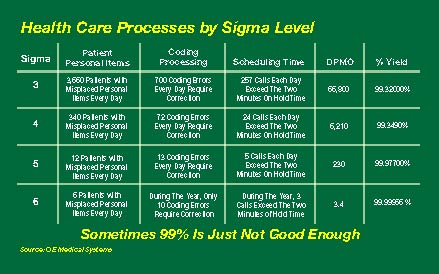

In the example cited at the outset of this article, the level of errors per million procedures under anesthesia puts this particular process at 5.97 Sigma, or nearly perfect. Figure 2 illustrates the impact of various Sigma levels on other common processes in a health care environment.

Figure 2. DMAIC flow chart demonstrating the steps to improve any existing product or process.

Achieving high reliability in health care demands a relentless focus on underlying, systemic causes for variation. This is unfortunately the opposite of the way many organizations approach errors or quality issues. Often there is a tendency to blame the people involved while retaining the same processes and systems that allowed the error to occur in the first place. This theme is evident in a new book written by two University of California-San Francisco Medical Center physicians entitled, Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America’s Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. Through a case-based approach, authors Robert M. Wachter, MD, UCSF Professor of Medicine, Chief of the M Service, and Chair of the Patient Safety Committee at UCSF Medical Center, and co-author Kaveh G. Shojania, MD, UCSF Assistant Professor of Medicine, share vital lessons about patient safety with the medical community and public at large.

Figure 3. Examples of Health Care Process by Sigma Levels.

Summary

Initial skepticism over any new improvement initiative is understandable, since most health care organizations have not been able to sustain results from previous programs like TQM, CQI, and PDCA. In fact, studies have shown that approximately 62% of change initiatives are destined to fail. Reasons for this may include a lack of leadership support, absence of control mechanisms to monitor change on an ongoing basis, less statistical rigor targeting standard deviation and not just averages, and failure to address the cultural or human side of change. Combining strong technical strategies such as Six Sigma and Lean with proven cultural strategies like Work-Out and Change Acceleration Process, is one approach that can take a hospital further down the path to HRO status.

Debate over particular solutions is healthy and should be driven by an accumulation of evidence. Denial that serious deficiencies exist, however, is no longer a fantasy we can afford. Becoming a HRO, like aiming for Six Sigma levels of excellence, is a worthy goal, one that can be supported by studying achievements in other industries such as aviation and examining success stories from “early adopter” hospitals and health systems.

At the risk of repeating a familiar phrase, it is not simply a matter of working harder, but working smarter. When discussing the need for change in health care, providers may bristle at words like “efficiency” and “productivity,” which imply slack that does not exist in most daily schedules. Cultural transformation involves putting a framework in place that makes it easier to do the right thing and far more difficult for errors to occur. Several critical attributes and capabilities can deliver results and support the quest to become a HRO:

- Acknowledgment of the need for change

- Data-driven methods for reducing process variation, defects, and waste

- Cultural techniques for acceptance building and change acceleration

- Measurable and accountable leadership development

- Well-defined and thoroughly utilized operating mechanisms

- Improvement initiatives visibly supported by management and clearly aligned with organizational objectives and values

- Ability to leverage and expand access to new technologies

- Collaboration and best practice sharing across and beyond health care.

Adapting stronger systems for identifying and eliminating risk should be seen as complementary to medical science. Implementing effective strategies to create highly reliable processes and organizations is imperative for the viability of the health system as well as the sake of the patient.

Without overlooking its unique challenges and obligations, health care can learn from best practices that have been successfully applied in other high-risk industries. We are all stakeholders when it comes to health care. Uniting the best of medical science and management science could be the marriage that saves the system.

Ms. Luchsinger is Principal, West Consulting, GE Healthcare. Ms. Pexton is Director of Communications, Performance Solutions with GE Healthcare Services in San Ramon, CA.

Suggested Reading/General References

- Roberts KH, Bea R. Must accidents happen? Academy of Management Executive 2001;15(August): 70-9.

- Pande P, Holpp L. What is Six Sigma? New York: McGraw Hill, 2002.

- Snee RD, Hoerl RW. Leading Six Sigma. CITY: FT Prentice Hall, 2003.

- Carroll JS, Edmondson AC. Leading organisational learning in health care. Qual Saf Health Care 2002; 11: 51-6.

- Chassin MR. Is health care ready for Six Sigma quality? Milbank Q 1998;76:565-91,510.

- Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press; 2000.

- Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America’s Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. New York: Rugged Land Publishers, 2004.

- Barach P, Small SD. Reporting and preventing medical mishaps: lessons from non-medical near miss reporting systems. BMJ 2000; 320:759-63.

- Gerowitz MB. Do TQM interventions change management culture? Findings and implications. Qual Manag Health Care 1998;6:1-11.

- Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q 1998;76:593-624,510.

Websites for more information

IsixSigma:

www.healthcare.isixsigma.com

International Society of Six Sigma Professionals:

www.isssp.com

GE Healthcare Services Performance Solutions:

www.gemedicalhcs.com

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

www.ahrq.org

Issue PDF

Issue PDF