To the Editor

In the Fall 2004 issue of the APSF Newsletter, Dr. Nichols et al. stressed the importance of machine check, especially of the reusable pieces of equipment to avoid a foreign body in the circuit causing high airway pressures (HAP) after intubation. This problem is not uncommon and continues to cause anxiety when encountered.

I am sure many of us follow a pattern of checks when confronting the problem of HAP after intubation. The order of these checks is decided by the preexisting problems of the patient, the machine, and also by previous encounters of a similar nature.

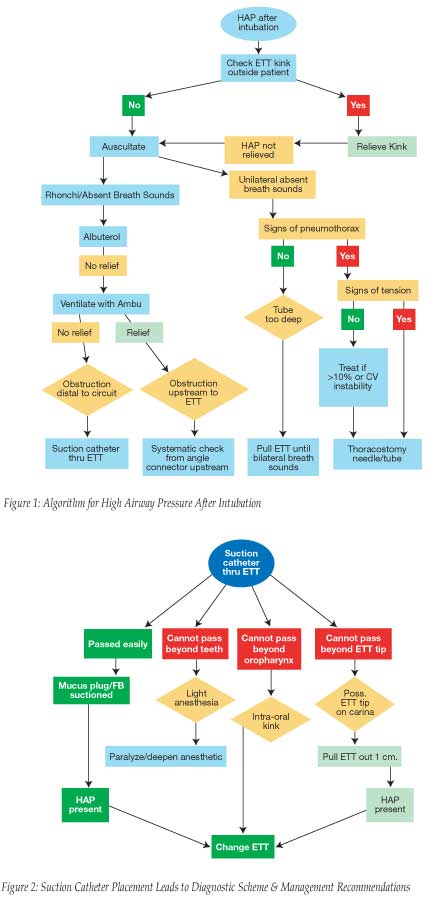

The checks have to be quick (time and life-saving), systematic, and cost-effective. The following sequence, although not exhaustive, may suit most of the circumstances (Figure 1) and is for the benefit of anesthesiologists who have not encountered HAP after intubation, and, it is hoped, will never have to use this algorithm.

On initial notice, it may be a good practice to put one’s hand under the drapes and feel for the ETT outside the patient, which may be obstructed by the surgeon’s hand or kinked due to the plastic’s inherent properties. Following that, perform auscultation of the chest to detect breath sounds. Precordial stethoscopes placed prior to draping come in handy. Rhonchi, or bilateral absent breath sounds, are treated by a dose of albuterol. If the HAP continues, start Ambu bag ventilation. If ventilation is easy, the obstruction is proximal to the ETT. This is approached systematically from either the angle piece and upstream or the ventilator and downstream, not forgetting that some of the causes missed are a stuck O2 flush valve, wrong vacuum settings in the scavenging system, and leak from ventilator bellows.

The causes of HAP distal to the angle piece are either from the patient or the ETT. With continuing anesthetic, by the intravenous route if necessary, pass a suction catheter down the ETT (Figure 2). This will give some information, depending on how far one is able to pass the catheter. Once the ETT is eliminated as a cause for HAP, the patient causes are approached while having in mind the preexisting problems of the patient and the sequence of events that led to the HAP. This systematic approach avoids changing the ETT unnecessarily with its attendant problems of laryngeal trauma, saves the time of reintubation, and is also cost-effective.

One can suitably modify the scheme shown in the tables for the individual circumstances depending on the degree of suspicion about a particular cause.

Hariharan Shankar, MD

Milwaukee, WI

Issue PDF

Issue PDF