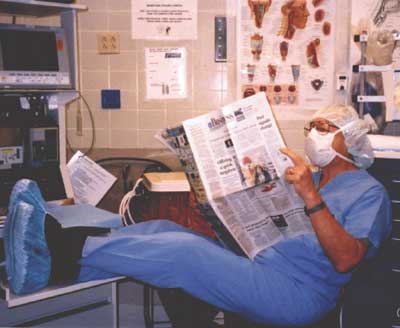

Perusing the business section of the Dallas Morning News, Dr. Giesecke demonstrates the bad practice of reading in the OR.

Like the stock market, which waxes and wanes in irregular, dysrhythmic undulations, the interest that residents and practitioners have in reading in the operating room (OR) follows a similar course. Recently, we have observed that reading in the OR has gradually crept back into our practice; it is in a waxing phase. We understand why anesthesiologists are tempted to read in the OR (“Watching surgery is like watching paint dry,” and “I have no time to read at home so I need to make up for lost time in the OR”). This subject became the focus of serious discussion in a panel on patient safety presented at the recent annual meeting of the Association of University Anesthesiologists in Sacramento, CA. We feel that reading in the OR seriously compromises patient safety and are opposed to it for the following 4 reasons:

First, reading diverts one’s attention from the patient. If, because one’s attention is diverted, 1 or 2 minutes of warning signals are missed, then the remaining time may not be adequate to evaluate the problem, make a diagnosis, and take corrective action. The consequence may be a severely injured patient. However, with improved monitoring techniques (pulse oximetry, capnography), it can be argued that this scenario is less likely.

Second, the patient is paying for our undivided attention, and most well-informed patients want to know if we plan to turn over a portion of their anesthesia care to a nurse or resident. If we are obliged to honestly answer that concern, then, should we also be obliged to inform the patient that we plan to read during a portion of the anesthetic? If patients knew, they would probably request a reduction in our fee for service or choose another anesthesiologist. On a personal level, we would not want the anesthesiologist caring for us or our family to read during surgery. Is it fair to provide less vigilance to our patients than we would expect during our own anesthetic?

Third, it is medico-legally dangerous. Any plaintiff’s attorney would love to have a case in which the circulating nurse would testify, “Dr. Giesecke was reading when the cardiac arrest occurred. Yep, he was reading the Wall Street Journal. You know he has a lot of valuable stocks that he must keep track of.” It is possible that if anesthesiologists informed their malpractice carriers that they routinely read during cases, the companies might raise premiums or cancel malpractice coverage.

Fourth, the practice of reading in the OR projects a negative public image. In this case, the nurses, technicians, aides, and surgeons represent the public. The officers of the ASA must occasionally serve as spokespersons for our profession at press conferences. Usually this follows a highly publicized disaster. It would be very difficult for them to defend the practice of reading in the OR. The public perception of our manner of practice is critical to the future integrity of the practice of anesthesiology. Let us strive to project an appropriate image. Reading in the OR should NOT be part of the image.

Despite our strong objections to reading in the OR, many of our colleagues feel differently. In 1995, Dr. Weinger wrote an article for the APSF Newsletter discussing the practice of reading in the OR and pointed out that there were no scientific data on the impact of reading on anesthesia provider vigilance.1 He concluded, “In the absence of controlled studies on the effect of reading in the operating room on vigilance and task performance, no definitive or generalizable recommendations can be made,” and the decision to read or not should be “a personal one based on recognition of one’s capabilities and limitations.”1 This commentary generated a flurry of letters to the editor from anesthesiologists supporting both sides of the issue. Advocates of reading said it was no different than “any conversation with another person in the operating room about topics unrelated to patient care” or “listening to music” during the procedure, while opponents called the practice “appalling” and “totally unacceptable.”

In an attempt to resolve the controversy, the APSF awarded a patient-safety grant to Dr. Weinger in 1997 for his project entitled “Scientific Evaluation of Anesthesiologist Performance: Further Validation and Study of the Effects of Sleep Deprivation and of Intraoperative Reading.” In a recent abstract, Weinger reported that anesthesia providers read in 35% of cases, but found no evidence that vigilance was different between reading and non-reading periods.2 He concluded that intraoperative reading by anesthesiologists “may have limited effects on vigilance and therefore may not a priori put patients’ safety at risk.”

While there appears to be no conclusive evidence that reading in the OR affects vigilance on the part of the anesthesiologist, we still object to this practice. Former President Bill Clinton was highly criticized for his affair with an intern, despite a lack of evidence indicating that this indiscretion affected his performance as president or adversely affected the country. When asked in a recent CBS television interview why he had an affair with Monica Lewinsky, Mr. Clinton responded, “For the worst possible reason: just because I could. I think that’s just the most morally indefensible reason that anybody could have for doing anything.” As anesthesiologists, we know that we can read in the OR and recognize that there is no scientific evidence that reading in the OR adversely affects a patient’s outcome. Would we, however, want to defend this practice in a television interview?

Dr. Monk is a Professor in the Department of Anesthesiology at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, and Dr. Giesecke is a Professor of Anesthesiology and Pain Management and Former Jenkins Professor and Chairman at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas TX.

References

- Weinger MB. In my opinion: lack of outcome data makes reading a personal decision, states OR investigator. APSF Newsletter 1995;10:3-5.

- Weinger MB. Assessing the impact of reading on anesthesia provider’s vigilance, clinical workload, and task distribution. Available on the web at: http://www.anestech.org/Publications/Annual_2003/sta117.html. Accessed on August 9, 2004.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF