Episode #40 Be On The Lookout for MH Look-Alikes

April 13, 2021Welcome to the next installment of the Anesthesia Patient Safety podcast hosted by Alli Bechtel. This podcast will be an exciting journey towards improved anesthesia patient safety.

Today, we are going to be talking about several syndromes with similar presentations to Malignant Hyperthermia. Our featured article today is from the February 2021 APSF Newsletter. The article is “Drug-Induced MH-like Syndromes in the Perioperative Period” by Charles Watson, Stanley Caroff, and Henry Rosenberg. You can find the article here. https://www.apsf.org/article/drug-induced-mh-like-syndromes-in-the-perioperative-period/

Many anesthesia professionals know about the MH Hotline supported by donations and the Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States. Volunteers field calls about recognition and treatment of MH crises, post-crisis management, and other conditions with similar presentations. Here is the link to the MHAUS website: https://www.mhaus.org

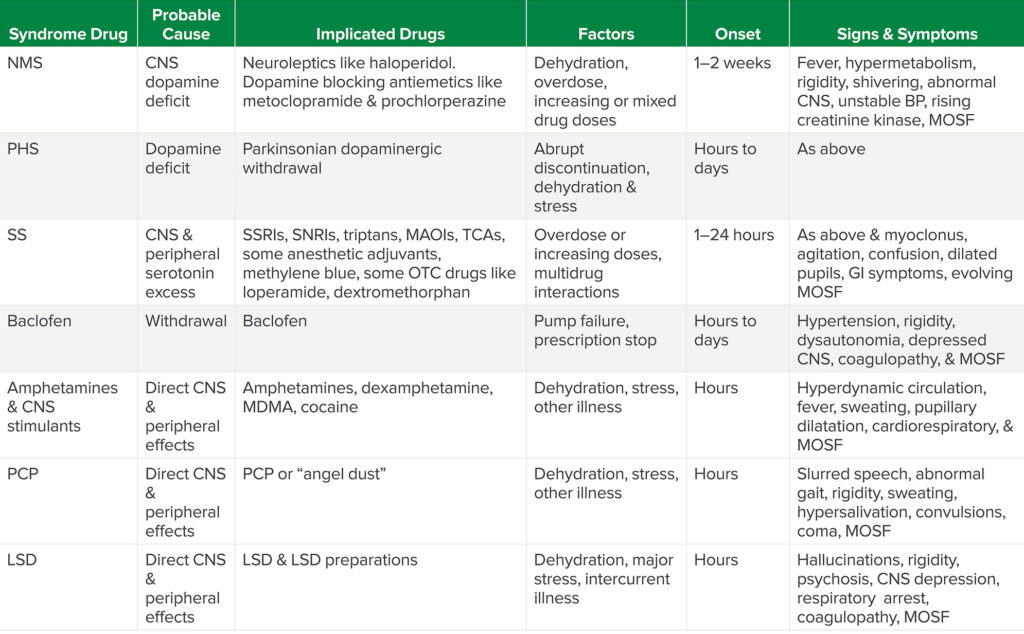

This chart includes important information about Drug-induced syndromes with similar presentations to malignant hyperthermia.

Table Abbreviations: NMS (neuroleptic malignant syndrome), CNS (Central Nervous System), MOSF (multiple organ system failure), PHS (Parkinsonism-Hyperpyrexia Syndrome), SS (Serotonin Syndrome), SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), SNRIs (selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), Triptans (a class of Triptamine-based drugs used to abort migraines & cluster headaches), TCAs (tricyclic antidepressants), MAOIs (Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors), OTC (sold without prescription “over the counter”), GI (gastrointestinal), MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine or “ectasy”), PCP (phencyclidine or “angel dust”), LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide).

For additional resources and help for suspected cases of neuroleptic malignant syndrome, check out the Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Information Service (NMSIS) which is sponsored by MHAUS. Here is the link: www.NMSIS.org

Be sure to check out the APSF website at https://www.apsf.org/

Make sure that you subscribe to our newsletter at https://www.apsf.org/subscribe/

Follow us on Twitter @APSForg

Questions or Comments? Email me at [email protected].

Thank you to our individual supports https://www.apsf.org/product/donation-individual/

Be apart of our first crowdfunding campaign https://www.apsf.org/product/crowdfunding-donation/

Thank you to our corporate supporters https://www.apsf.org/donate/corporate-and-community-donors/

© 2021, The Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation

Hello and welcome back to the Anesthesia Patient Safety Podcast. My name is Alli Bechtel and I am your host. Thank you for joining us for another show. We are going to start with a patient presentation today. A patient presents with rising temperature, tachycardia, tachypnea, increasing hypercarbia, confusion, agitation, altered mental status, muscle rigidity, cramping, tremor, spasms, cardiac arrhythmias, and either hypertension or hypotension. What is going on?

Before we dive into today’s episode, we’d like to recognize Acacia Pharma, a major corporate supporter of APSF. Acacia Pharma has generously provided unrestricted support to further our vision that “no one shall be harmed by anesthesia care”. Thank you, Acacia Pharma – we wouldn’t be able to do all that we do without you!”

And now, back to our patient presentation…what is going on with this patient? Did Malignant Hyperthermia cross your mind? I listed signs and symptoms that may be consistent with MH or Drug-induced MH-like syndromes. I hope that you will keep these signs and symptoms in mind as we review our featured article today from the February 2021 APSF Newsletter. The article is “Drug-Induced MH-like Syndromes in the Perioperative Period” by Charles Watson, Stanley Caroff, and Henry Rosenberg. I will include a link to the article in the show notes. You can follow along with us by clicking on the Newsletter heading, 1st one down is the current issue. From the February 2021 Newsletter page, scroll down looking in the left hand column until you see the featured article.

The authors open the article with a review of malignant hyperthermia which is a rare, rapidly progressing, life-threatening, hypermetabolic syndrome triggered by potent inhalational anesthetic agents and/or succinylcholine. This is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder. It affects skeletal muscle such that after exposure to the triggering agent there is uncontrolled release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum due to altered calcium release receptors leading to this hypermetabolic syndrome. It is important that anesthesia professionals recognize MH and very quickly provide appropriate treatment by discontinuing any triggering agents, administering Dantrolene, and providing supportive care. Be on the lookout for increases in temperature, HR, CO2 production, end-tidal CO2, respiratory rate, spontaneous or required minute ventilation, muscle tone with rigidity. Patient are at risk for multiple organ system failure including kidney failure, cardiac and microcirculatory failure and coagulopathy, hepatic failure, and ultimately death.

Malignant Hyperthermia is known as an anesthetic-related problem since it is often seen following administration of volatile anesthetics and succinylcholine and anesthesia professionals are trained to recognize and treat MH. We are going to shift gears to talk about other significant hypermetabolic conditions induced by certain medications due to abnormal CNS activity. As we talked about earlier, the signs and presentation are very similar to MH. Drug-induced hypermetabolic syndromes are less common in the operating room, but they may present throughout the perioperative time period since certain medications that are either given or held for anesthesia and surgery may trigger the syndrome. We will get more into the specific syndromes soon. Unlike MH, anesthesia medications often are not the sole triggering agent. Outside of the OR, patients are more likely to be evaluated and treated for this medical emergency by emergency medicine, neurology, psychiatry, and critical care professionals. It is important for anesthesia and other healthcare professionals to recognize central drug-induced hypermetabolic conditions since these patients are at risk for increased morbidity and mortality, it is not MH but has a similar presentation, and the treatment may be different. Like MH, the fever is unlikely to be treated with antipyretic drugs, but Dantrolene may be helpful to treat the fever associated with muscle hyperactivity and heat production from the CNS problems. Also, it may be helpful to avoid anticholinergic and medications with anticholinergic properties since this prevents heat dissipation and sweating. Throughout the evaluation and treatment, other conditions to keep on the differential should include encephalitis, sepsis, CNS abscess, tumor, head trauma, stroke, thyrotoxicosis, heatstroke, and untreated lethal catatonia.

Many anesthesia professionals know about the MH hotline supported by donations and the Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States and I will include a link in the show notes. The volunteers field calls about recognition and treatment of MH crises, post-crisis management, and other conditions with similar presentations. It is no surprise that some of the calls to the hotline are related to drug-induced hypermetabolic syndromes such as Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome or NMS, Parkinsonism/Hyperthermia Syndrome, Serotonin Syndrome, Baclofen withdrawal, and intoxication caused by stimulants like amphetamine, MDMA and cocaine, and psychoactive drugs like phencyclidine (PCP) and LSD.

With that, let’s talk about some of these syndromes and I will include the chart from the article in the show notes. It is a great quick reference guide and review. We’ll start with Neuroleptic-Malignant Syndrome or NMS. This is a rare condition that may occur in the setting of chronic or increasing doses of neuroleptic medications, such as Haloperidol and metoclopramide. These medications inhibit dopaminergic activity in the brain. Patients with psychotic disorders may present to the OR while taking neuroleptic medications. These medications are also used for sedation, behavioral control for emergence delirium, to treat PONV or for prophylaxis in the PACU and ICU postoperatively. The risk for NMS is increased in patients who are sick, dehydrated, agitated, and catatonic. Prochlorperazine which is used to treat nausea may cause NMS is susceptible patients. Presentation with fever, abnormal muscle activity and rigidity, and altered mental status may occur hours or up to 2 weeks after initiation of neuroleptic therapy. Treatment involves early recognition, discontinuing the medication, and supportive care with gradual improvement in symptoms. When NMS goes unrecognized patients are at risk for muscle injury, cardiorespiratory failure, and death. The diagnosis may be challenging and depends on history and physical exam while excluding other causes or conditions. Other treatment modalities may be helpful to consider including benzodiazepines, dopaminergic drugs including bromocriptine or amantadine, dantrolene, and ECT (electroconvulsive therapy). For additional resources and help for suspected cases of NMS, check out the Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Information Service (NMSIS) which is sponsored by Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States. I will include the link in the show notes as well.

The next syndrome is Parkinsonism-Hyperthermia Syndrome. This occurs when centrally acting dopaminergic medications used for patients with Parkinson’s disease are stopped. This may occur if the medications are held preoperatively to minimize the autonomic side effects or if the medications are stopped abruptly due to certain medical and surgical conditions. When these dopaminergic medications are stopped suddenly, 4% of patients will develop this syndrome and about 30% will have long-term effects. Presentation includes fever, abnormal muscle activity, autonomic instability and other signs of hypermetabolic activity. Once again, patients at increased risk include those who are sick and dehydrated or patients who receive central dopamine-blocking drugs or neuroleptics such as Droperidol and Haloperidol, respectively. This syndrome may also occur following sudden discontinuation of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease or even following implantation of the electrodes for deep brain stimulation. This is a syndrome caused by withdrawal and this is why it is so important that dopaminergic medications should not be completely discontinued perioperatively if possible. If these medications need to be held preop, then it is vital that the medications are restarted postop as soon as possible.

We are moving on to the third syndrome which is Serotonin Syndrome which occurs following increased central serotonin levels from certain drug combinations or single drug overdose. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that can be found in the brain, GI tract, or on platelets with central and peripheral effects including regulation of mood, appetite, sleep, some cognitive functions, platelet aggregation, and smooth muscle contraction of uterus, bronchi, and small blood vessels. Medications that increase central serotonin levels include such antidepressant medications as the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), the Selective Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs), the tricyclic antidepressants, and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Serotonin syndrome has an incidence of 0.9-2% associated with chronic medication therapy and 14-16% following an overdose with the SSRIs and the SNRIs being the most common to cause Serotonin Syndrome. The authors include a list of antidepressant, anesthesia, and other medications that may cause serotonin syndrome in the article and I encourage you to check it out. I am going to list the anesthesia adjuncts and other medications now though, so get ready. Here we go: Cocaine, Meperidine, Methadone, Ondansetron, Tramadol, Fentanyl and Buspirone Cyclobenzaprine, Dextromethorphan, 5-hydroxytryptophan Linezolid, Loperamide, Methylene blue, and St. John’s wort.

Presentation may include altered mental status, autonomic dysfunction, hypotension, neuromuscular rigidity, agitation, ocular and peripheral clonus, diaphoresis, and fever with an onset time shortly after drug administration or overdose. You need to be on the lookout for this because the initial symptoms may progress to cardiorespiratory failure, muscle damage, organ failure, and death. Treatment includes stopping any drugs that may increase Serotonin levels and providing supportive care. Cyproheptadine, a central 5-hydroxytriptamine 2a receptor blocker, administration may be a useful adjunct for treatment of the hyperthermia associate with Serotonin Syndrome.

Okay, we have 2 more syndromes to cover. The next one on the list is Baclofen withdrawal. Baclofen is a medication that augments the effects of the inhibitory CNS neurotransmitter, GABA. It is used to treat spasticity associated with cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, and dystonia and can be administered as an oral medication or by direct injection or infusion into the cerebrospinal fluid. Anesthesia professionals and pain medicine specialists are often involved in prescribing this medication and inspecting and refilling baclofen pumps. It is important to stay vigilant for signs of baclofen withdrawal which may look an awful lot like MH including fever, altered mental status, autonomic hyperactivity, respiratory distress, rhabdomyolysis, and coagulopathy. Treatment includes restarting Baclofen therapy and providing supportive care.

We sure have reviewed a lot of syndrome today and we have one more to go. Patients using or who overdose from certain recreational drugs may present with symptoms similar to MH. Amphetamines, dextroamphetamine, methamphetamine, MDMA, cocaine, and PCP and LSD have certain direct peripheral and central nervous system effects that may cause a hypermetabolic syndrome. It is important to evaluate patients prior to surgery with a drug history or toxicology screening when necessary but keep in mind that patients may present emergently to the OR or they may present for elective surgery. Presentation may include altered mental status, abnormal motor activity, fever, and hypermetabolism which may progress to cardiorespiratory failure. Treatment includes delaying elective surgery and providing supportive care. It is vital to keep recreational drug use on your differential since patients may use these drugs to help them relax prior to surgery and the timing of symptoms onset is variable.

That was a great review of several very important conditions that may mimic MH. Just as anesthesia professionals need to be knowledgeable about MH including being able to recognize and treat quickly, it is just as important that anesthesia professionals can recognize and treat quickly these other hypermetabolic syndromes. While Dantrolene is the mainstay of treatment for MH, it may also have a role for other hypermetabolic syndrome treatment, but it does not treat the cause of these other syndromes and misdiagnosis may delay or prevent the necessary treatment such as stopping or re-starting certain medications. This is the time to stay vigilant during these hypermetabolic crises to help keep patient safe during anesthesia care.

That’s all the time we have for today. If you have any questions or comments from today’s show, please email us at [email protected].

Visit APSF.org for detailed information and check out the show notes for links to all the topics we discussed today. Please keep in mind that the information in this show is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical or legal advice. Have you joined the conversation on twitter? If so, we would love for you to tag us in a tweet using #ASPF podcast and tell us where you like to listen to the show. Thanks for listening and we can’t wait to hear from you!

Until next time, stay vigilant so that no one shall be harmed by anesthesia care.

© 2021, The Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation