Episode #215 Protecting Pediatric Patients from Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression: Expert Insights and Strategies

August 14, 2024Welcome to the next installment of the Anesthesia Patient Safety podcast hosted by Alli Bechtel. This podcast will be an exciting journey towards improved anesthesia patient safety.

Our featured article today is from the June 2024 APSF Newsletter. It is “Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression—Pediatric Considerations” by Tricia Vecchione, and Constance L. Monitto.

Thank you so much to Connie Monitto for contributing to the show today.

Here are the key takeaways:

- This is a preventable complication

- Anesthesia professionals need to be able to identify high-risk patients

- Utilize opioid-sparing adjuncts

- Perform frequent sedation assessment

- Maintain vigilant monitoring

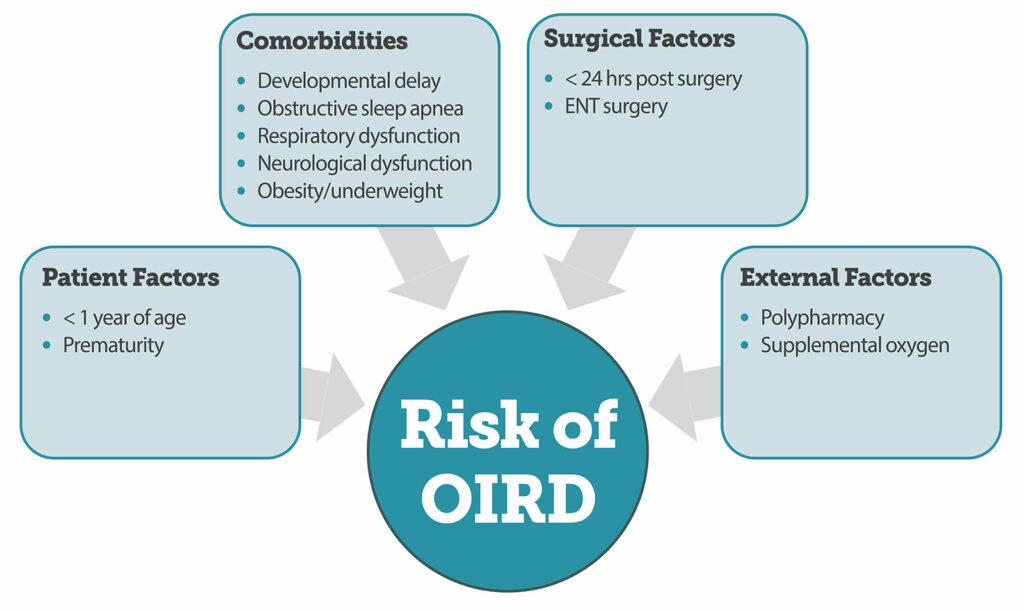

Here are the pediatric risk factors for opioid-induced respiratory depression from Figure 1 in the article.

Figure 1. Summary of risk factors associated with increased risk of Opioid Induced Respiratory Depression {OIRD) in children.4,10

Here is the citation to the article the we discussed today.

Coté, Charles J. MD*; Posner, Karen L. PhD†; Domino, Karen B. MD, MPH†. Death or Neurologic Injury after Tonsillectomy in Children with a Focus on Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Houston, We Have a Problem!. Anesthesia & Analgesia 118(6):p 1276-1283, June 2014. | DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318294fc47

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel here: https://www.youtube.com/@AnesthesiaPatientSafety

Be sure to check out the APSF website at https://www.apsf.org/

Make sure that you subscribe to our newsletter at https://www.apsf.org/subscribe/

Follow us on Twitter @APSForg

Questions or Comments? Email me at [email protected].

Thank you to our individual supports https://www.apsf.org/product/donation-individual/

Be a part of our first crowdfunding campaign https://www.apsf.org/product/crowdfunding-donation/

Thank you to our corporate supporters https://www.apsf.org/donate/corporate-and-community-donors/

Additional sound effects from: Zapsplat.

© 2024, The Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation

Hello and welcome back to the Anesthesia Patient Safety Podcast. My name is Alli Bechtel, and I am your host. Thank you for joining us for another show. We are jumping back into the June 2024 APSF Newsletter. Today, we are talking about a very important patient population, pediatric patients, and a very important threat to anesthesia patient safety, opioid-induced respiratory depression. Stay tuned.

Before we dive into the episode today, we’d like to recognize Fresenius Kabi, a major corporate supporter of APSF. Fresenius Kabi has generously provided unrestricted support to further our vision that “no one shall be harmed by anesthesia care”. Thank you, Fresenius Kabi – we wouldn’t be able to do all that we do without you!”

Our featured article today is from the June 2024 APSF Newsletter. It is “Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression—Pediatric Considerations” by Tricia Vecchione, and Constance L. Monitto. To follow along with us, head over to APSF.org and click on the Newsletter heading. The first one down is the current issue and from here, scroll down until you get to our featured article today. I will include a link in the show notes as well.

To help kick off the show today, we are going to hear from one of the authors. Let’s take a listen now.

[Monitto] “Hi, my name is Connie Monitto. I’m a pediatric anesthesiologist at the Charlotte Bloomberg Children’s Center of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.”

[Bechtel] I asked Monitto why she wrote this article. Let’s take a listen to what she had to say.

[Monitto] “I wrote this because most articles about opioid induced respiratory depression focus on risk assessment and mitigation in the care of adult patients. But I’m a pediatric anesthesiologist with a special interest in acute pain management. That means I need to prescribe opioids to children while keeping them as safe as possible.

Physiology evolves as children age and so does their ability to communicate. That can affect our assessment of their pain and our treatment choices. Besides that, monitoring that can be easy to implement in cooperative adults isn’t always successful when you’re caring for children because they don’t always cooperate.

These differences mean we need to do more than just extrapolate results from adult studies when we’re trying to minimize risk for our youngest and most vulnerable patients.”

[Bechtel] Thank you so much to Monitto for helping to kick off the show today. Now it’s time to get into the article. Here we go.

Let’s start with some key takeaways. This is a vital topic since opioid-induced respiratory depression can be a life-threatening complication in children. This is a preventable complications and anesthesia professionals need to be able to identify high-risk patients and take steps to keep their patients safe including the following:

- Opioid-sparing adjuncts

- Frequent sedation assessment

- Vigilant monitoring

There are no models available currently to help predict the risk of opioid-induced respiratory decompensation in children, so we need to utilize multiple and complementary monitors to help decrease and prevent serious opioid-induced respiratory depression.

Now, it’s time to take a step back. Opioid-induced respiratory depression is a big threat to anesthesia patient safety and as a result, the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation and other institutions and professional societies have developed recommendations for patient monitoring. The appropriate level for postoperative monitoring may be guided by preoperative assessment of patient-specific risk factors. The current published guidelines are geared towards adults, but what about children, who are not just little adults? Pediatric patients are also at risk for perioperative respiratory complications, and we need to look at pediatric-specific risk factors to help keep these patients safe.

Check out Figure 1 in the article for a summary of risk factors in children. These have been determined from patient audits and data tracking administration of naloxone which is a surrogate indictor for opioid-induced respiratory depression. I will include this figure in the show notes, and we are going to go through it now.

Here are the risk factors for increased risk of opioid-induced respiratory depressions:

- For Patient Factors, age less than one year of age and prematurity

- For Comorbidities, developmental delay, obstructive sleep apnea, respiratory dysfunction, neurological dysfunction, and obesity or underweight.

- For surgical factors, less than 24 hours after surgery and ENT surgery

- And for external factors, polypharmacy and supplemental oxygen.

For pediatric patients, there is a 2014 retrospective review that looked at naloxone administration for critical respiratory events. The authors found that there was an increased incidence associated with younger age and prematurity and this is thought to be due to the physiologic difference in metabolism and excretion of opioids between infants, older children, and adults. If we look at morphine, there is a longer half-life and lower clearance in newborns. This means that infants less than one month of age may see higher serum levels that decrease more slowly compared to older children and adults leading to an increased risk for respiratory depression. In addition, pediatric patients with obstructive sleep apnea, OSA, are at increased risk. This has been studied after tonsillectomy. Children with severe OSA are at high risk for morphine-induced respiratory depression and require less morphine than children with mild sleep apnea. It is important to screen for OSA in children since it is relatively common with an incidence of between 1-5%. Preoperative screening may be difficult though since there is no validated risk assessment questionnaire that can be used for all children. Plus, polysomnography which is the gold standard for diagnosis is not available for most pediatric patients.

Check out the 2014 article in Anesthesia and Analgesia, “Death or Neurologic Injury after Tonsillectomy in Children with a Focus on Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Houston, We Have a Problem!” by Charles Coté and colleagues. I will include the citation in the show notes as well. The authors conclude that at least 16 children who suffered death or neurologic injury after tonsillectomy from apnea could have been rescued with continued respiratory monitoring during recovery and on the ward on the first postoperative night. Important risk factors include obesity, history of OSA, and the need for postoperative opioid increases the risk for adverse respiratory events. Decreased doses of opioids may be required in the following situations: children with severe OSA due to increased opioid sensitivity related to hypoxia-induced opioid receptor regulation and children who are ultrarapid metabolizers of codeine who have a fast conversion to morphine leading to overdose. Table 5 in the article provides risk factors for OSA, some of which include obesity, history of reactive airway disease, male gender, enlarged tonsils, loud snoring, unusual sleep positions, and poor performance in school. These pediatric specific risk factors can help us to identify children at increased risk for OSA who may not have a formal diagnosis.

Another risk factor for naloxone administration is childhood obesity which may be due to the relationship between obesity and OSA or inappropriate dosing. Weight-based dosing is common for pediatric medication administration, but dose adjustment is needed since opioid dosing based on total body can lead to respiratory depression. It is important to use ideal or lean body mass instead of total body weight. Children who are underweight are also at risk for respiratory events.

Next up, let’s talk about the risks of polypharmacy. Levels of sedation and central nervous system depression can be increased by co-administration of anxiolytics, muscle relaxants, anticonvulsants, and other sedating medications. When these medications are combined with opioids, there is an increased risk for adverse respiratory events and naloxone administration. The co-administration of opioids with other CNS depressants is common for pediatric patients according to a 2010 survey of pediatric pain management practice. 40% of respondents reported allowing co-administration of these medications. Practices may have changed over the past 14 years, but there is concern for continued polypharmacy especially with the focus on opioid-sparing techniques and multimodal analgesia. Clinicians need to remain especially vigilant in the postoperative period since the highest risk for postoperative respiratory depressions occurs within postoperative day #1. 75% of episodes of naloxone administration in children for respiratory events occur in the first 24 hours after surgery. Patients who required naloxone had received opioids from different routes including intravenous, oral, and neuraxial.

We have discussed the risk factors so now it is time to talk about the current recommendations for monitoring of pediatric patients. The authors highlight that experts suggest continuous monitoring of oxygenation and ventilation for at least 24 hours postoperatively in pediatric patients who receive opioids. Is this the practice at your institution? Let me just repeat, that experts suggest continuous monitoring of oxygenation and ventilation for at least 24 hours postoperatively in pediatric patients who receive opioids.

The APSF has been a long-time advocate for continuous electronic monitoring of oxygenation and ventilation, when supplemental oxygen is provided, to preemptively identify and potentially prevent opioid induced respiratory depression. We have talked about this on the podcast before in episode #162: No Patient Should be Harmed by Opioid Induced Respiratory Depression and we hope that you will also check out the June 2023 APSF NL article, “Opioid Induced Respiratory Depression— Beyond Sleep Disordered Breathing” by Toby Weingarten. This article focuses on adults, and we are expanding the discussion this year to include pediatric patients. There are no studies that evaluate different monitoring requirements for pediatric patients, but we can look at the consensus statement endorsed by the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia which supports extra vigilance in the care of select patients, including neonates, children with OSA, and those with underlying neuromuscular diseases or cognitive impairment, which can impact respiratory muscle function and/or impede assessment of the patient’s level of pain or consciousness. It is also critical to increase monitoring and vigilance for pediatric patients who are just starting on opioid therapy especially in the immediate postoperative period, those receiving escalating doses of parental opioids, and those receiving opioids in addition to other CNS depressant medications. Experts recommend continuous monitoring of respiratory rate and pulse oximetry for the first 24 hours unless the patient is awake and actively being observed for all pediatric patients who are started on parenteral opioids, who receive opioids by patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), or PCA by proxy, and/or continuous opioid infusion. It does appear that continuous monitoring in children is more common especially when an opioid PCA was provided. Continuous respiratory rate monitoring was not used consistently.

Check out figure 2 in the article for a visual representation of the type of patient monitoring used when opioids are administered to pediatric patients. This was based on a 2010 survey study with 149 total respondents. As you can see, pulse oximetry was used frequently when opioids were administered to children by PCA, PCA with basal infusion, continuous opioid infusion, as needed opioids, and PCA by proxy. ECG monitoring and capnography were often used in conjunction with pulse oximetry and respiratory inductive plethysmography was used with pulse oximetry, but occasionally as the only continuous monitor.

The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia provide additional recommendations for the use of perioperative opioids in children which include the following:

- Regular assessment of level of sedation using a validated sedation score that evaluates the patient’s level of alertness. This is an important assessment that is different from using a scale to monitor procedural sedation. You may consider using the Pasero opioid sedation scale.

- When starting opioid therapy for infants younger than 3 months of age, admission to a highly monitored environment such as the ICU, PACU, or step-down unit.

- Continuous monitoring of respiratory rate and electrocardiogram for pediatric patients receiving supplemental oxygen therapy. Remember, supplemental oxygen may decrease the sensitivity and response time of pulse oximetry as a monitor for apnea or hypopnea.

We still have more to talk about when it comes to keeping pediatric patients receiving opioids safe during anesthesia care. We hope that you will tune in next week when we discuss respiratory monitoring for pediatric patients and the associated challenges. Plus, we are going to hear from the author again.

If you have any questions or comments from today’s show, please email us at [email protected]. Please keep in mind that the information in this show is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical or legal advice. We hope that you will visit APSF.org for detailed information and check out the show notes for links to all the topics we discussed today.

Are you following the APSF on social media? The APSF is on Facebook, X, Instagram, LinkdIn, YouTube and TikTok. I will include a link to all of our social media handles in the show notes. We hope that you will follow us for video recaps, important updates, new literature, and more. The ASPF is bringing you the latest in perioperative anesthesia patient safety and we hope that you join the conversation and follow along with us.

Until next time, stay vigilant so that no one shall be harmed by anesthesia care.

© 2024, The Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation