Postoperative visual loss (POVL) has received heightened attention in the anesthesiology, ophthalmology, and spine literature for almost 10 years now. We have made significant progress in disseminating the knowledge to the anesthesiology community regarding the different types of injuries to the visual system that can occur perioperatively, such as central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO), ischemic optic neuropathy (ION), and cortical blindness. Data from the ASA POVL Registry have clearly demonstrated that ION, the most common diagnosis in our database, has a distinct perioperative profile from that of CRAO patients. ION occurred with patients’ heads suspended in Mayfield pins without globe compression, was commonly bilateral, and was associated with large blood loss (median 2.0 liters) and long anesthetic/operative times (≥6 hours anesthetic duration).1 These associated features of ION are consistent with an injury caused by physiologic perturbations in susceptible patients, rather than direct trauma, as can occur with CRAO. The vast majority of patients in the ASA POVL Registry who developed ION were relatively healthy (ASA 1-2), and it has been reported in patients as young as 10 and 13 years of age after spine surgery.2,3 These findings suggest that any patient may be susceptible to developing this devastating perioperative complication, regardless of age or health status. Whether or not these patients who develop ION perioperatively have atypical physiology or vascular anatomy of their optic nerves remains unknown.

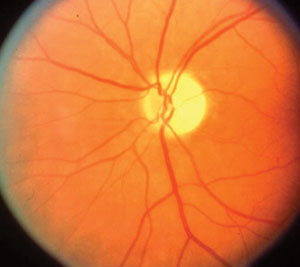

Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (late exam with optic nerve pallor) (Photo courtesy of Dr. Sohan S. Hayreh, University of Iowa)

Though we now have a few more pieces of the puzzle of the etiology of ION, solving this mystery will require significantly more research in one or more directions such as 1) clinical multicenter retrospective case control studies or prospective multicenter observational studies; 2) development of an animal model for ION utilizing physiologic perturbations to create an injury of the optic nerve; 3) development of a reliable intraoperative optic nerve function monitor; and 4) studies of patients who have developed ION after spine surgery to determine if their physiology or anatomy is unique.

Until there is definitive evidence on the etiology and prevention of ION, the ASA Task Force on Perioperative Blindness has issued a Practice Advisory for Perioperative Visual Loss Associated with Spine Surgery with the following recommendations for major spine surgery cases:

- consider consenting patients for the risk of POVL

- use indwelling arterial catheters to monitor blood pressure, and consider use of a central venous catheter

- use colloids along with crystalloids for volume replacement

- position the head so that it is equal or above the level of the heart

- consider staging procedures.4

Because of the significant variability in the blood pressure and transfusion management in patients who develop ION, no recommendations could be made for these areas.

Dr. Lee is Director of the ASA Postoperative Visual Loss Registry, Associate Editor of this Newsletter, and Associate Professor of Anesthesiology at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

References

- Lee LA, Roth S, Posner KL, Cheney FW, Caplan RA, Newman NJ, Domino KB. The American Society of Anesthesiologists Postoperative Visual Loss Registry: analysis of 93 spine surgery cases with postoperative visual loss. Anesthesiology 2006;105:652-9.

- Chang SH, Miller NR. The incidence of vision loss due to perioperative ischemic optic neuropathy associated with spine surgery: the Johns Hopkins Hospital Experience. Spine 2005;30:1299-302.

- Kim JW, Hills WL, Rizzo JF, Egan RA, Lessell S. Ischemic optic neuropathy following spine surgery in a 16-year-old patient and a ten-year-old patient. J Neuroophthalmol 2006;26:30-3.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blindness. Practice advisory for perioperative visual loss associated with spine surgery: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blindness. Anesthesiology 2006;104:1319-28.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF