I am the head of cardiothoracic anesthesia at St. John’s Mercy Medical Center in St. Louis and have had a unique failure of one of our newer anesthesia machines that I (and our equipment committee chairman) believe has not been reported. The machine features a keyboard-driven interface that controls all monitors, gas flows, and all ventilator functions. In short, the ventilator/vaporizer screen became unresponsive to all input and therefore the vaporizer and ventilator controls could not be changed in the middle of a case. I changed out machines (with lots of help) uneventfully, and our equipment technician and biomed person discovered that the designers had installed a number of hidden keys (for future upgrades) one of which became intermittently activated by surface damage. When activated, it locked out all the other controls thereby locking the ventilator and the vaporizer controls.

I would be very grateful for your advice in this matter.

Sincerely,

Kit Young, MD

St. Louis, MO

In Response:

Dear Dr. Young,

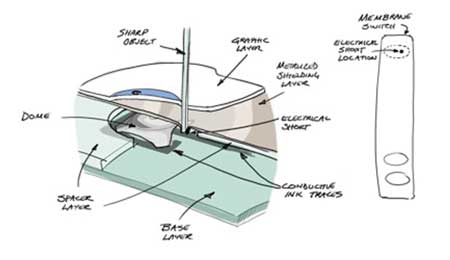

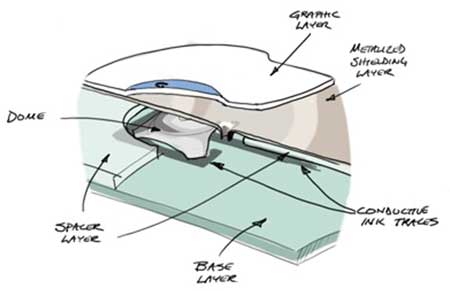

The failure was indeed caused by damage to the keypad, as you reported. This damage could have resulted in failure of the keypad regardless of whether it occurred on an unlabeled (“hidden”) key area or on a labeled key. It is unfortunate that it was difficult to detect because the visible signs of the damage were small, and the damage was apparently not reported when it occurred. Subsequent examination of the sample you provided revealed a small hole in the keypad. The object that created this small hole was inserted with enough force to push the metal shield on the circuit board into the circuit layer of the keypad, causing an electrical short circuit (see Figures 1a and 1b). It was this electrical short circuit that caused the keypad to fail.

Figure 1a: Sharp object inserted into the keypad. This pushed the metal shielding layer through the spacer layer and into the conductive trace, causing an electrical short circuit.

Figure 1b: After the sharp object was removed. Note the electrical short circuit caused by contact of the metal shielding layer to the conductive ink trace is still there. The short circuit in this case was intermittent

Membrane-type keypads are commonly used in many types of approved medical equipment and are generally quite durable, rugged, and reliable.

While anesthesia machines are designed to be rugged, they unfortunately cannot be made to be completely indestructible. It is true that some types of damage could lead to failure of a machine component. The design process for an anesthesia machine includes a Hazard Analysis and FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis), with the intent that a failure of any component will not result in a direct hazard, whether it be to the patient, machine operator, or others in the area. In this case the machine performed as designed when faced with a failure of the keypad—it continued to operate with the last known ventilation, fresh gas, and vaporization settings. Switching to manual (bag) ventilation is always an available option if needed. Switching to 100% oxygen is also available through an alternate, adjustable O2 delivery system, which concurrently discontinues vaporization. And discontinuation of vaporization alone (with retention of second gas) is accomplished by removal of the agent cassette.

This case does illustrate the importance of reporting any damage when it occurs, even if it appears small and the device seems to function correctly. Best course of action is to have the device checked thoroughly by a qualified service person or trained biomedical engineer before placing it back in service. Hidden damage can lead to possible component failure or degradation at a later time, as indeed happened in this case. This applies to any component of the machine, not just to the keypad.

It is important that all individuals who work around medical devices, especially life support equipment, are aware of the need to immediately report any damage or suspected damage to the equipment. Perhaps this case can serve as an illustration to re-emphasize the need for this knowledge and awareness. Thank you for sharing your experience.

Sincerely,

Kevin Tissot

Engineering Manager, Anesthesia Platforms

Life Support Solutions – GE Healthcare

Issue PDF

Issue PDF