It was not really very long ago that the lay public considered the anesthetic to be the riskiest part of a surgical procedure. In the 1970s and early 1980s, most anesthesia malpractice claims involved death or permanent brain damage. During this time, which coincided with escalating malpractice premium costs as well as a new emphasis on anesthesia patient safety, the ASA Closed Claims Project began. The goal was to identify major areas of loss in order to suggest strategies for injury prevention. If anesthesia became safer and patient injuries were reduced, malpractice premiums should follow suit.

While anesthesia malpractice claims do not paint a picture of overall patient safety and anesthetic risk, they provide valuable insights into important risks and safety problems. Since claims provide a ready-made set of data on injuries, collected in central locations with detailed records and investigation, they provide a cost-effective method of identifying some major risks to anesthesia patient safety. The nature of the U.S. legal system creates a bias toward severe injuries in claims data, and this approach provides data to attack those severe injuries first. Other methods will be required to learn about causes and prevention of less severe injuries, such as dental damage.

Some Stipulations About Closed Claims Data

The Closed Claims Project Database consists of standardized summaries of closed anesthesia malpractice claims collected from anesthesia liability insurers from throughout the United States. Data collection is by volunteer ASA members and funding is from the ASA through the Committee on Professional Liability. A closed claim is a claim that has been dropped, settled, or adjudicated by the courts. Anesthesia claims take anywhere from six months to over 10 years to close. On average, it takes five years between the date of an injury to the entry of a claim into the Closed Claims Project Database. Claims are included in the database if the nature of the injury and the sequence of events can be reconstructed from the insurance company records. Since many minor claims are dropped without comprehensive investigation by the insurance company, closed claims will be biased toward more severe injuries. Claims for damage to teeth and dentures are all excluded. We know that not all injuries result in a claim, while some claims are filed without a clear injury or without a substantiated relationship between the anesthesia care and the injury. Thus our sample of closed claims does not represent all claims, and especially not all injuries. In most of the claims in the database (82%), a lawsuit was filed.

Changing Profile of Anesthesia Liability

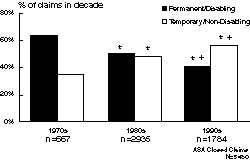

Figure 1: Trends in severity of injury. The proportion of claims with permanent and disabling injuries (including death) declined over decades. “Decade” is when the anesthetic was administered, typically 3-5 years before the claim closed and entered the ASA Closed Claims Project Database. *p=0.05 compared to 1970s; +p=0.05 compared to 1980s

When the Closed Claims Project began in 1984, claims were retrospectively collected and dated back to events that occurred throughout the 1970s. Thus, the database of 5480 claims includes 667 claims (12%) from events that occurred in the 1970s, 2935 (54%) from 1980-89, and 1784 (33%) from the 1990s. Most of the 1784 claims from the 1990s involved events occurring prior to 1995.

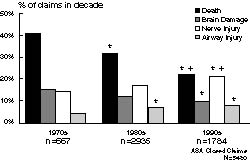

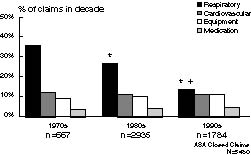

A dramatic shift in severity of injury is apparent over time. In the 1970s, 64% of claims involved permanent and disabling injuries or death. In the 1990s, this percentage was down to 41% (Figure 1). Most claims (57%) in the 1990s involved temporary and non-disabling injuries. The most common injuries are shown in Figure 2. Death and brain damage no longer account for the majority of claims. As a proportion of claims, nerve injury has increased, as has airway injury. Death and brain damage have declined from 56% of claims in the 1970s to 32% in the 1990s, while airway injury has doubled from 4% to 8% of total claims. Nerve injury now represents 21% of claims, with spinal cord injury becoming the leading type of nerve injury claim in the 1990s. Other cited injuries in the 1990s include burns and skin inflammation (6%), awareness, recall, and emotional distress (5%), eye injury (5%), backache (5%), headache (4%), pneumothorax (4%), aspiration pneumonitis (3%), and newborn injury (1.5%). In the 1970s, respiratory events such as inadequate ventilation, esophageal intubation, and difficult intubation were the most common events leading to claims (Figure 3). These have declined substantially, from 36% of claims in the 1970s to 14% of claims in the 1990s. Most of the improvement in respiratory events involved the near elimination of claims for undetected esophageal intubation and inadequate ventilation (although a few still occurred in the 1990s). Other common causes of claims have remained relatively unchanged: cardiovascular events and equipment problems each account for 11% of claims, and medication errors account for another 4%. Many claims, including many for nerve injury and airway injury, occur without any identifiable or recorded untoward event.

Figure 2: Most common complications in closed claims. Complications are the injuries to the patient that were alleged to have resulted from anesthesia care. *p=0.05 compared to 1970s; +p=0.05 compared to 1980s

Figure 3: Most common damaging events in closed claims. The “damaging event” is the mechanism that allegedly caused the injury. *p=0.05 compared to 1970s; +p=0.05 compared to 1980s

The payment profile appears to reflect the improved distribution of injuries in anesthesia claims. In the 1970s, 64% of claims were closed with payment. In the 1990s, only 45% of claims resulted in payment. While the absolute dollar amount of payments has remained fairly stable at a median of $100,000 for claims that are paid, if adjusted for inflation the financial loss would show a decline.

New Areas of Anesthesia Liability

New areas of anesthesia liability in the 1990s include ambulatory surgical anesthesia, office-based anesthesia, and non-surgical pain management. In the U.S. overall, about half of all surgeries are conducted on an outpatient basis. In the ASA Closed Claims Project Database, ambulatory surgical anesthesia claims represent 25% of all claims from the 1990s, an increase from only 11% in the 1980s and nearly none earlier. Most of these claims involve temporary and non-disabling injuries. Office-based anesthesia is a more recent trend than ambulatory anesthesia, and consequently, there are currently very few office-based anesthesia claims in the ASA Closed Claims Project Database. As we collect claims from the late 1990s, this liability profile may change. Non-surgical pain management procedures account for 8% of closed claims from the 1990s, an increase from 2% in the 1970s and 3% in the 1980s.

Summary

The widely recognized increasing safety of anesthesia seems to be reflected in the profile of anesthesia liability. The 1990s present a profile of fewer claims for death and brain damage and fewer respiratory system mishaps than preceding decades. This improved injury profile is reflected in fewer payments. If a payment was made, the inflation adjusted amount of payment has declined over the past three decades.

Further information and a complete list of publications is available at: www.asaclosedclaims.org

Recent ASA Closed Claims Findings:

Cheney, FW: The American Society of Anesthesiologists Closed Claims Project: What Have We Learned, How Has it Affected Practice, and How Will It Affect Practice in the Future? Anesthesiology 1999;91:552-6.

Cheney FW, Domino K B, Caplan RA, Posner KL: Nerve injury associated with anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 1999;90:1062-9.

Domino KB, Posner KL, Caplan RA, Cheney RW: Airway injury during anesthesia. A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 1999;91:1703-11.

Domino KB: Office-based anesthesia: lessons learned from the Closed Claims Project. ASA Newsletter 2001;65(6):9-11, 15.

Fitzgibbon DR: Liability arising from anesthesiology-based pain management in the nonoperative setting. ASA Newsletter 2001;65(6):12-15.

Posner KL: Liability profile of ambulatory anesthesia. ASA Newsletter 2000;64(6):10-12.

Dr. Posner is Research Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.