| Adapted from Special Feature on Pulse Oximeters: The invention that changed the paradigm of patient safety around the world. (LiSA (1340-8836) vol28 No3 Page237-308, 2021.03 (in Japanese)

Disclaimer: The information provided is for safety-related educational purposes only, and does not constitute medical or legal advice. Individual or group responses are only commentary, provided for purposes of education or discussion, and are neither statements of advice nor the opinions of APSF. It is not the intention of APSF to provide specific medical or legal advice or to endorse any specific views or recommendations in response to the inquiries posted. In no event shall APSF be responsible or liable, directly or indirectly, for any damage or loss caused or alleged to be caused by or in connection with the reliance on any such information. |

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, anesthesia adverse events had reached a tipping point. It was approximated that anesthesia related mortality prior to 1985 was 1:10,000 healthy patients.1 A highly publicized 1982 ABC 20/20 program entitled “The Deep Sleep: 6000 Will Die Or Suffer Brain Damage,” projected that 6000 patients undergoing general anesthesia would die or suffer brain damage that year.2 The 1984 ASA President (and eventual founding APSF President), Ellison C. Pierce Jr., MD, was particularly concerned about these emerging statistics at the time. Therefore, he helped to create collaborative changes that contributed to a reduction in anesthesia mortality to less than 1/200,000 in healthy patients in developed nations, today.

First, Dr. Pierce created the ASA Committee on Patient Safety and Risk Management and the Standards Committee, whose initial purpose was to create monitoring standards to reduce the late recognition of preventable adverse anesthesia related events.3 Dr. John Eichhorn, secretary of the committee at the time (and subsequent founding editor of the APSF Newsletter, conveyed the unpublished (at the time) “Harvard Monitoring Standards,” to the committee as a model to be adopted for the entire ASA constituency.4 Standards included pulse oximetry, which was created by the late Dr. Takuo Aoyagi from Japan, coupled with capnography were true innovations that provided anesthesia professionals with the appropriate sensory signals to detect earlier patient deterioration. Interestingly, a review of the effect of introducing monitoring standards suggested greater than a fivefold decrease in serious adverse events after implementation of the monitoring standards.5 Similarly, malpractice claims had also dropped significantly with the addition of the ASA Monitoring Standards.6

Dr. Pierce did not stop his quest to improve anesthesia patient safety with his ASA related organizational efforts. In the late 1970’s, Ellison C. Pierce Jr’s colleague, Jeffery B. Cooper, PhD, a bioengineer at the Massachusetts General Hospital, was focusing his research expertise on investigating how human errors were a significant cause of preventable anesthesia catastrophies.7 Early on in the anesthesia safety movement, Dr. Pierce recognized the value of a multiprofessional approach to improving patient safety. He teamed up with Dr. Cooper and others to create likely the first ever International Symposium on the Prevention of Anesthesia Mortality and Morbidity, held in Boston, MA in 1984.7 It was at this monumental meeting that Dr. Pierce posed the idea about creating an anesthesia safety foundation whose goal would be to improve anesthesia safety education, awareness and research worldwide. When asked what to call such an organization, Dr. Cooper naturally replied, the “Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation, APSF.”7 Based on the visionaries’ discussions at this meeting, a new safety period began and the APSF officially created its vision “that no patient shall be harmed by anesthesia,” on October 2, 1985. In addition, the APSF established its goals:8

- Establish an APSF Newsletter to be given to all anesthesia professionals free of charge that informs them of anesthesia patient safety related topics.

- Sponsor research that facilitates a clearer understanding of preventable anesthetic injuries.

- Encourage educational programs that may aid in reducing preventable anesthetic injuries.

- Promote national and international dialogue and exchange of ideas with regard to causes and prevention of anesthetic injuries.

The following essay will focus on the APSF’s contribution to anesthesia patient safety as it relates to the following original 4 goals stated above.

The APSF Newsletter

The APSF Newsletter has been the pillar of the APSF organization since its inception in 1985. It has and remains the voice and the vehicle by which to gather and disseminate perioperative patient safety education for its large constituency which now extends to the international community. Its leadership has always made it a priority to produce high quality multiprofessional patient safety information that can provide potential templates for anesthesia professionals on how to engage in safe perioperative care of patients.

Dr. John Eichhorn was chosen by the first APSF President, Ellison C. Pierce Jr., to be the founding Editor-in-chief of the APSF Newsletter in 1985.3 He naturally brought his past journalism and newspaper editing skills to life in the form of the quarterly, APSF Newsletter. The Newsletter has exposed unsafe practices that require improvement in a multidisciplinary manner, since its first issue in 1986 (https://www.apsf.org/newsletter/spring-1986/), which was sent out to 45,000 recipients (ASA, American Association of Nurse Anesthetists (AANA), risk managers, and corporate supporters).3 That first issue highlighted the need for minimal intraoperative monitoring requirements and a summary of the crucial creation of the ASA Closed Claims Study, which seeks to codify areas of anesthesia-related injury or death and subsequently develop strategies for prevention.9 It also reported on the potential patient harm caused by hypoxemia and hypercarbia and the disastrous consequences of wrong site surgery.9

Anesthesia standards were a focal point of the APSF Newsletter during its first year. Reports by the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI), a non-profit organization whose goal is to improve safety and quality across worldwide healthcare settings, reported on mortality associated with general anesthesia particularly focusing on incorrect placement and verification of the endotracheal tube in the trachea.9 In 1987, an APSF Newsletter article summarized the FDA’s discussion on anesthesia machine checkout standards (https://www.apsf.org/article/anesthesia-machine-standards-enhance-safety/) and this was followed up by the 1992 amendments to the ever important “Anesthesia Apparatus Recommendations,” which accounted for the key checks in use today (https://www.apsf.org/article/comments-sought-on-new-fda-preanesthesia-checklist/).

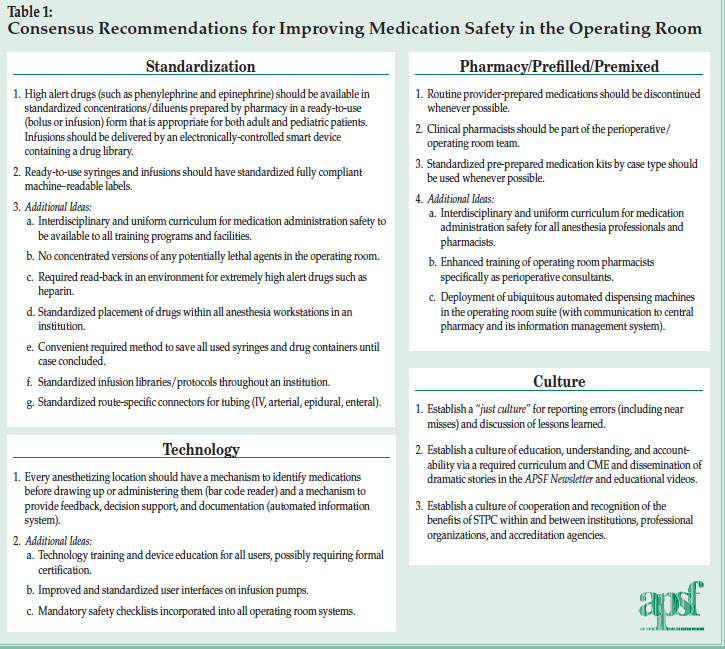

In addition to anesthesia standards, the APSF Newsletter focused on look-a-like medication errors which first appeared in a 1987 issue. In fact, medication errors are so important to patient safety that the APSF Newsletter published over 130 articles on the topic, including summarizing results from two APSF sponsored conferences. The APSF called for and reported on a new paradigm, The STPC (Standardization, Technology, Pharmacy, and Culture) (See Table 1). This paradigm set out to prevent vial and ampule swaps, mislabeling and syringe swaps and remains a focal point around the US for medication safety (https://www.apsf.org/article/apsf-hosts-medication-safety-conference/).

Table 1 Depicts the Consensus Recommendations for Improving Mediation Safety in the Operating Room using the STPC algorithm.

Reproduced and modified with permission from author and APSF Newsletter.

Eichhorn JH. APSF Hosts Medication Safety Conference. APSF Newsletter 2010; 25: 1, 3-8.

Other key anesthesia patient safety topics were highlighted in the APSF Newsletter between 1990-2001. ECRI was the first organization to alert healthcare professionals about the threat of operating room fires and its etiology (fuels, oxidizers, and igniters-See Figure 1).9 The APSF saw this as a clear patient safety issue and helped to develop a safety algorithm and fire safety video to educate all healthcare professionals on how to prevent and manage operating room fires. 9 The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority has since reported a reduction in surgical fires.10

Figure 1. Depicts the APSF Sponsored Operating Room Fire Prevention Algoirthm

Reproduced and modified with permission from author and APSF Newsletter.

Lake C, Cowles C, Ehrenwerth J. Surgical Fire Prevention. APSF Newsletter 2020; 35: 84.

Similarly, the APSF Newsletter alerted its constituency in 1998 of the rise in patients experiencing postoperative visual loss (POVL) after spine surgery in the prone position. Risk factors were reported in Anesthesiology and the APSF Newsletter and included male sex, obesity, Wilson surgical frame, longer anesthetic duration, greater estimated blood loss, and lower percent of colloid in non-blood fluid administration.11 Numerous articles in the Newsletter along with collaboration from the ASA, APSF, and other US national organizations resulted in a 2.7 fold reduction in the incidence of POVL from 1998 to 2012.12

The APSF was one of the first organizations to recognize the deleterious effects to patient safety of production pressure, provider burnout and fatigue.13 Pioneers from the APSF originally wrote a landmark article on California’s anesthesiologists attitudes towards production pressure and its effects on the anesthesia work environment.14 The APSF followed this article up with distribution of a videotape on production pressure in 1998. A Special Issue of the APSF Newsletter entitled “Special Issue: Production Pressure – Does the Pressure to Do More, Faster, with Less, Endanger Patients? Potential Risks to Patient Safety Examined by APSF Panel,” focused on the multidisciplinary approach to improve the dilemma of balancing the ever increasing US healthcare focus on productivity, while maintaining patient safety.15 Today, this topic remains a major concern for patient and provider safety in the perioperative period.

Other essential anesthesia patient safety concepts were introduced in the APSF Newsletter and include human factors in anesthesia error analysis, smart alarms for anesthesia delivery systems, operating room (OR) crisis management, the risk of anesthesia for obstructive sleep apnea patients, and postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Similarly, the Newsletter was recognized by its readership for initiating discussions on hot topics such as the risk of succinylcholine in children, carbon monoxide production by CO2 absorbents, cardiac arrest after spinal anesthesia, lidocaine toxicity from tumescent liposuction, anaphylaxis induced by sulfites in propofol, bacterial contamination in propofol glass ampules, sevoflurane contamination, gas pipeline errors causing death, and distractions in the operating room.9

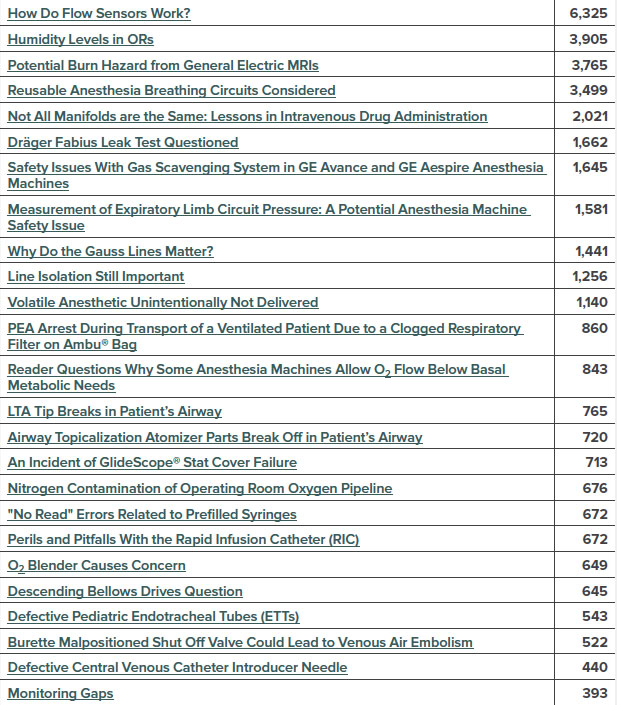

In 2002, Dr. Robert Morell, a mentee of Dr. Eichhorn, assumed the Editor-in-chief position of the APSF Newsletter. With Dr. Morell’s leadership, the Newsletter circulation grew from approximately 45,000 to 122,000 and the Newsletter changed to full color with expansion of special articles translated into Chinese. Key topics discussed during Dr. Morell’s tenure included anesthesia implications of chemical, biological and nuclear terrorism, cerebral hypoperfusion associated with surgeries performed in the beach chair position, maternal safety bundles, and a special issue on residual neuromuscular blockade (2016) and its deleterious effects on patients. In addition, Dr. Morell along with Dr. Michael Olympio were pioneers of the ever popular column “Dear SIRS (Safety Information Response System, now called Rapid Response).16 The Rapid Response column highlights APSF’s commitment to solve medical device issues that anesthesia professionals face by convening stakeholders in patient safety that include industry professionals. The APSF Committee on Technology (Jeffrey Feldman, MD-Current Chair) has been integral in developing excellent relationships with industry representatives so that safer technology is available for the anesthesia community.16 In its inaugural article in the Spring of 2004, a certified nurse anesthetist, an anesthesiologist, and representatives from Datex-Ohmeda recognized and rectified an issue involving occlusion of the exhaust line from the scavenging system.16 Since this monumental article, nearly 100 articles have been published in this column and typically appear in every APSF Newsletter. Figure 2 depicts the Top 25 Rapid Response accessed articles during the most recent years of 2018-2020.16 The Rapid Response column and its leadership remains committed to solving complex device problems in a multidisciplinary fashion. No other journal facilitates the extent of accessibility for time-sensitive patient safety material.

Figure 2. Depicts The Top 25 RAPID Response Articles by Page Views, May 1, 2018-2020.

Reproduced and modified with permission from author and APSF Newsletter.

Feldman J. RAPID Response and the APSF Mission. APSF Newsletter 2020; 35: 99.

In 2018, Dr. Steven Greenberg, assumed the Editor-in-chief position from Dr. Morell. At the same time the APSF Board of Directors (a multidisciplinary, multiprofessional group) convened at its yearly meeting to vote on the organization’s Top 12 Patient Safety Priorities (see Table 2).17 In the last two years, the APSF Newsletter has focused its attention on addressing all top 12 priorities. In 2018, each issue addressed the ongoing problem of opioid induced ventilatory impairment (OIVI). With the rising number of preventable deaths associated with OIVI, the APSF Newsletter invited experts to discuss key topics that included an examination of the closed claims database involving OIVI, methods for monitoring OIVI, the perspective of the Joint Commission, and a review of the impact on prescribing practices.18

Table 2. APSF Perioperative Patient Safety Priorities

| 1. Preventing, detecting, and mitigating clinical deterioration in the perioperative period |

| 2. Safety in non-operating room locations |

| 3. Culture of safety |

| 4. Medication safety |

| 5. Perioperative delirium, cognitive dysfunction, and brain health |

| 6. Hospital-acquired infections and environmental microbial contamination and transmission |

| 7. Patient-related communication issues, handoffs, and transitions of care |

| 8. Airway management difficulties, skills, and equipment |

| 9. Cost-effective protocols and monitoring that have a positive impact on safety |

| 10. Integration of safety into process implementation and continuous improvement |

| 11. Burnout |

| 12. Distractions in procedural areas |

| Published on the APSF website: https://www.apsf.org/patient-safety-initiatives/ |

| Reproduced and modified with permission from author and APSF Newsletter. Lane-Fall M. APSF Highlights 12 Perioperative Patient Safety Priorities. APSF Newsletter 2018; 33: 33. |

In addition to discussing the Top 12 Patient Safety Priorities, the APSF Newsletter leadership continued its quest to become an international anesthesia patient safety journal. Dr. Katsuyuki Miyasaka from Tokyo, Japan, authored a well-received article on the Japanese culture of safety in anesthesia in 2016.19 This article and author ignited a relationship with key anesthesia safety leaders (Drs. Hiroki Iida, and Tomohiro Sawa) from Japan and the APSF Newsletter to help create the first ever translated APSF Newsletter in Japanese. This translated Newsletter became the model for the APSF Newsletter being translated into 4 additional languages (Chinese, Spanish, French, and Portuguese). Our esteemed colleagues from Japan have substantially contributed to safety articles in the APSF Newsletter that include topics associated with sugammadex induced anaphylaxis and recurarization.20,21 In addition, they helped to encourage other members of the international APSF editorial board to contribute articles on topics such as emergency manual use in China, global simulation education, and worldwide critical incident reporting. With the international interest and contribution, visitors to the APSF International Newsletter has grown 3000% in the last three years to approximately 370,000. The APSF is committed to growing our safety community worldwide.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit the anesthesia community. The APSF Newsletter immediately worked with experts around the US to publish the article “Perioperative Considerations for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)”, which was recently updated in the June 2020 APSF Newsletter issue.22 This landmark article was translated in 6 languages and distributed throughout the world to provide guidance on safe approaches to managing COVID-19 patients in the perioperative period. To date, it has had 245,000 pageviews worldwide. It also discusses joint recommendations from the American College of Surgeons (ACS), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), American Hospital Association (AHA), and the Association of Perioperative Nurses (AORN) on how to safely resume perioperative services during this pandemic.22 In addition, the APSF teamed up with the ASA to develop a frequently asked questions section to answer some of the difficult questions that anesthesia professionals have regarding managing COVID-19 patients. It has provided our readership with discussions regarding COVID-19 testing, HEPA filter use for anesthesia machines, negative vs. positive pressure operating rooms and their use during COVID-19, repurposing anesthesia machines for ICU ventilation of COVID-19 patients, and appropriate use of personal protective equipment. Please visit https://www.apsf.org/covid-19-and-anesthesia-faq/ for further discussions on COVID-19 addressed by the APSF. The efforts of the APSF and its Newsletter regarding the COVID-19 pandemic have elevated its readership to 1,000,000 unique readers worldwide. The APSF will continue to educate our national and international constituency of the latest patient safety information as it relates to the ongoing pandemic and other emerging patient safety threats.

APSF Research

The APSF has provided more than $13.5 million to 145 principle investigators for anesthesia safety science research.23 The results of the APSF sponsored research has undoubtedly led to a greater global knowledge base of anesthesia patient safety and improved patient outcomes. When the organization began in 1985, there was little research opportunity in the patient safety domain. The APSF became the first organization dedicated to patient safety. The first grants were awarded in 1986 and were $35,000.24 However, in 2000, the award increased to $65,000 and in 2007 it increased to the current amount of $150,000.24 Since its inception, the grants have also expanded from just APSF sponsored to the ASA, industry and other organizations. Over the 30 plus year history of the grant program, the APSF has averaged $400,000 per year. A survey performed by the APSF evaluated the effectiveness of its research program and included a total of 76 responses from 71 different principle investigators (PIs).24

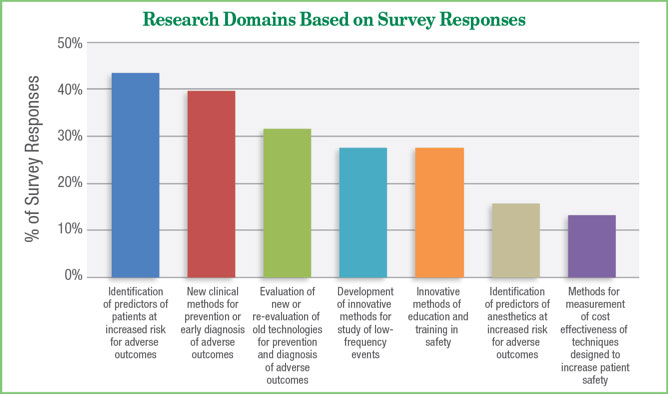

The corresponding survey revealed that a wide variety of safety topics have been addressed by the APSF sponsored research program. The most common subjects include identification of predictors of patients at increased risk of adverse events (43.4%), new methods for prevention or early diagnosis of disasters (39.5%), evaluation of new or reevaluation of existing technologies for prevention and diagnosis of adverse incidents (31.6%), creation of methods for the study of low frequency events (27.6%) and measuring cost-effectiveness of technologies designed to improve patient safety (13.2%) (see Figure 3).24

Figure 3. Depicts the APSF Research Program Study Subject Categories.

Reproduced and modified with permission from author and APSF Newsletter.

Urman R, Posner KL, Howard SK, Warner MA. 2017 Marks 30 Years of APSF Research Grants. APSF Newsletter 2018;32: 57.

Many of these research projects translated into a significant impact on patient care. Projects in the early years of the program focused on human factors research, simulation, crisis management, developing checklists, patient monitoring and alarm development. Perhaps some of the most impactful research funded by the APSF was in the field of simulation. These grants helped facilitate investigation on improving technical skills (e.g., airway assessment and management), team dynamics, educational assessment, health system integration, and crisis resource management.24 One notable study in this domain created an adjustable airway task trainer to be able to conform to a variety of anatomic configurations. This design has been used in several other research projects, publications and in resident training.25

Other topics supported by the APSF research program include the effects of surgery on patient postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction, the effects of perioperative hypothermia on bleeding and wound infection, novel approaches to difficult airway identification, and understanding the risk factors and incidence of perioperative visual loss. Risk assessment of opioid induced ventilatory impairment among children and adults, preoperative evaluation, techniques to improve communication and the use of big data to investigate perioperative outcomes have all been supported by the APSF program.24

The APSF Research Program has also provided a pathway by which participants receive and provide mentorship. Several of the respondents to the APSF Research Program survey reported that the APSF funding facilitated collaborations with national and international experts in their specific field, while allowing for maintenance of an academic career in times where funding was limited. The funding in many ways validated patient safety research as a legitimate academic career. As proof of this, the survey revealed that 86% of the recipients are still actively involved in patient safety science research today.24 In addition, a majority of the grant research recipients conducted additional research activities related to their original work and received grants from other national organizations. In summary, the APSF Research Program has resulted in improved patient outcomes, development of successful safety scientist careers, and high impact publications throughout its 34 year history.24

APSF Sponsored Educational Programs

Since 2001, the APSF has held a consensus conference (now called the Stoelting Conference in honor of past president, Robert K. Stoelting, MD), which has become one of the primary mechanisms by which to identify current patient safety issues and solutions. The organization convenes a group of multidisciplinary, multiprofessional stakeholders to provide action plans to improve patient safety. A complete list with summaries of each consensus conference is available at https://www.apsf.org/past-apsf-consensus-conferences-and-recommendations/. A few of these conferences outcomes will be highlighted.

Audible Alarms & Dangerous By-Products

Many of the consensus conferences led to further efforts to improve patient safety by facilitating collaboration with national organizations or by promoting research that provided the appropriate pathway. In 2004, the audible alarms workshop resulted in a call to set critical audible alarms and avoid disabling them so that appropriate alarms signals could lead to an early warning of potential adverse events (https://www.apsf.org/article/apsf-workshop-recommends-new-standards/).

Similarly, in 2005, the APSF provided recommendations as to the management of potentially dangerous by-products and reactions as a result of volatile anesthetic exposure to CO2 absorbent ( https://www.apsf.org/article/carbon-dioxide-absorbent-desiccation-safety-conference-convened-by-apsf/).

Opioid Induced Ventilatory Impairment

In 2006, the APSF held a workshop on improving the detection of postoperative opioid-induced respiratory depression. After engaging its multiprofessional audience of over 100 participants, it strongly urged health care professionals to consider the potential safety value of continuous monitoring of oxygenation (pulse oximetry) and ventilation in patients receiving opioids in the postoperative period (https://www.apsf.org/article/dangers-of-postoperative-opioids/).

Beach Chair Position

The potential dangers of the beach chair position were discussed at the 2009 conference and recommendations included maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion by taking into account height differences between the brain and the site at where the blood pressure is measured. Awareness has been heightened among anesthesia professionals today in part due to these efforts (https://www.apsf.org/article/cerebral-perfusion-err-on-the-side-of-caution/; https://www.apsf.org/article/apsf-workshop-cerebral-perfusion-experts-share-views-on-management-of-head-up-cases/).

Medication Safety

The APSF has prioritized medication safety throughout its history. In fact, two consensus conferences were designated to this topic. The organization has created an educational video, and published numerous articles on medication safety in the APSF Newsletter. (https://www.apsf.org/article/apsf-hosts-medication-safety-conference/; https://www.apsf.org/videos/medication-safety-video/). In 2018, focus groups were developed to partner with national organizations to identify and promote safer anesthetics, to share information, simplify ordering, establish contingency plans for drug shortages, reduce drug administration errors and standardize and innovate medication safety methods across disciplines (https://www.apsf.org/medication-safety-recommendations/).

Postoperative Visual Loss (POVL)

The APSF convened a consensus conference on perioperative visual loss and worked with surgeons to develop a video on the appropriate way to consent patients who undergo surgical procedures in the prone position with higher risk for POVL (https://www.apsf.org/article/apsf-sponsored-conference-on-perioperative-visual-loss-develops-consensus-conclusions/; https://www.apsf.org/videos/perioperative-visual-loss-povl-video/).

Emergency Manuals/Checklists

In 2015, the APSF Consensus Conference addressed implementing emergency manuals/checklists. Subsequently, the APSF has lead in advocating, educating, and researching the implementation of manuals/checklists in the operating room to make patients safer (https://www.apsf.org/article/apsf-sponsors-workshop-on-implementing-emergency-manuals/).

Perioperative Handoffs: Achieving Consensus on How to Get it Right

In 2017, the Stoelting Conference focused on transitions of care. Using the delphi method with the participants, the APSF developed consensus recommendations on the conduct, training, implementation, and research of perioperative handoffs. This conference also helped to create the Perioperative Multicenter Handoff Collaborative (MHC), which is sponsored by the APSF. The MHC is a multidisciplinary consortium of healthcare professionals whose goal is to create evidence based strategies to eliminate patient harm from poor communication and teamwork during perioperative handoffs (https://www.apsf.org/article/first-stoelting-conference-reaches-consensus-on-many-perioperative-handover-recommendations/).

Perioperative Deterioration: Early Recognition, Rapid Intervention, and the End of Failure to Rescue

Perhaps one of the most innovative conferences occurred in 2019 and involved human factors and design experts engaging the participants to design actual potential solutions to failure to rescue patients who are deteriorating in the perioperative period. Nineteen prototypes were created and encompassed the following domains: technology/data integration, culture/recognition, appropriate training, and system workflow/ decision support tools (https://www.apsf.org/past-apsf-consensus-conferences-and-recommendations/apsf-stoelting-conference-2019-summary/).

National and International Exchange of Anesthesia Patient Safety Ideas

APSF Educational Videos

Over 10,000 copies of perioperative patient safety videos such as on-patient fires in the operating room, medication safety, opioid-induced ventilatory impairment, and postoperative visual loss have been distributed by the APSF by download, DVD, or the website (www.apsf.org). The fire safety video alone has been accessed over 8,000 times and is used to raise awareness and teach health care professionals how to prevent and respond to operating room fires (https://www.apsf.org/resources/fire-safety/).

APSF National & International Communication Growth

Our readership continues to grow from its over 100,000 circulated hard copies to now over 1,000,000 unique website visitors around the world in 2020. Since the inaugural Japanese translated Newsletter in 2017, we have developed 4 other translated and customized APSF Newsletters in French, Chinese, Spanish, and Portuguese. Our online visitors to the international newsletters have grown over 3000% in just 3 years. Collaboration with national experts on COVID-19 and the rapid innovation of our interactive website and social media components of the APSF communications team has driven our Newsletter traffic up considerably.

The APSF’s approach to delivery of safety content to its national and international constituency has also evolved considerably since 2015. The APSF social media ambassador program, the online website safety educational posts (www.apsf.org) and the new anesthesia patient safety podcasts (https://www.apsf.org/anesthesia-patient-safety-podcast/) have all enhanced its worldwide audience’s ability to more easily access current patient safety information. Prior to this complete make-over, the website would see 33,000 visitors per year and now its hosts over 2000/day. It was one of the first safety organizations to publish expert opinion pieces on safe COVID-19 practices for anesthesia professionals. To provide more accessibility for our international audience, the APSF has translated these top COVID-19 related articles into different languages as well. The organization continues its commitment to engaging its international audience and to partner with them to find solutions on current patient safety issues.

Conclusion

The APSF has enjoyed a rich 35 year history of innovation, collaboration and commitment to anesthesia patient safety. Starting with the monitoring standards, the organization’s leaders remain focused on creating and supporting education and research as it relates to new patient safety threats and those related to its current top 12 initiatives.

Dr. Aoyagi’s invention that enormously increased sensitivity to early hypoxemia fueled the beginnings of the patient safety movement in anesthesia where standard monitoring was born. His actions of persistence and perseverance were most admirable and serve as the model by which to produce effective technology to improve patient safety. The APSF encourages all safety scientists and healthcare professionals to continue the quest for patient safety solutions as Dr. Aoyagi did nearly 35 years ago so that “No patient shall be harmed by anesthesia care.”

Steven Greenberg, MD, is current editor-in-chief of the APSF Newsletter and Secretary of the APSF. He is vice chairperson, Education, in the Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine at NorthShore University HealthSystem and clinical professor in the Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care at the University of Chicago.

A special thanks to Dr. John Eichhorn for his countless contributions to patient safety and his review of this manuscript.

References

- Lagasse R. Anesthesia safety: model or myth?: a review of the published literature and analysis of current original data. Anesthesiology 2002; 97: 1609-17.

- “The Deep Sleep: 6000 Will Die or Suffer Brain Damage.” 20/20. April 22, 1982.

- Eichhorn JH. The APSF at 25: Pioneering Success in Safety, But Challenges Remain 25th Anniversary Provokes Reflection, Anticipation. APSF Newsletter 2010; 25: 21.

- Eichhorn JH. ASA 1986 Monitoring Standards Launched New Era of Care, Improved Patient Safety. APSF Newsletter 2020; 35: 71, 74-5.

- Eichhorn JH. Monitoring standards: role of monitoring in reducing risk of anesthesia. Problems in Anesthesia 2001; 13: 430-443.

- Holzer JE. Risk manager notes improvement in anesthesia losses. APSF Newsletter 1990; 5: 1.

- Eichhorn JH. The Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation at 25: A Pioneering Success in Safety, 25th Anniversary Provokes, Reflection and Anticipation. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2012; 114: 791-800.

- Greenberg S. Pioneer in Patient Safety and Simulation Speaks at the International Forum on Perioperative Quality and Safety. APSF Newsletter 2018; 32: 87.

- Eichhorn JH, Morell R, Greenberg S. “What Then?” and “What Now?” 35th Anniversary Edition of the APSF Newsletter. APSF Newsletter; 35: 71-73.

- Surgical fires: decreasing incidence relies on continued prevention efforts. Pa Patient Saf Advisory 2018; 15 (2). Available at http://patientsafety.pa.gov/ADVISORIES/Pages/201806_SurgicalFires.aspx accessed on October 28, 2020.

- Lee LA, Roth S, Posner Kl, et al. The American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Postoperative Visual Loss Registry: analysis of 93 spine surgery cases with postoperative visual loss. Anesthesiology 2006; 105: 652-659.

- Rubin DS, Parakati I, Lee LA, et al. Perioperative visual loss in spine fusion surgery: ischemic optic neuropathy in the United States from 1998-2012 in the nationwide inpatient sample. Anesthesiology 2016; 125: 457-464.

- Prielipp RC. Production Pressure and Anesthesia Professionals. APSF Newsletter 2020; 35: 87-89.

- Gaba DM, Howard SK, Jump B. Production pressure in the work environment. California anesthesiologist’s attitudes and experiences. Anesthesiology 1994; 81: 488-500.

- Morell RC, Prielipp RC. Special Issue: Production Pressure-Does the Pressure to Do More, Faster, with Less, Endanger Patients? Potential Risks to Patient Safety Examined by APSF Panel. APSF Newsletter 2001; 16: 1.

- Feldman J. Rapid Response and the APSF Mission. APSF Newsletter 2020; 35: 99-100.

- Lane-Fall M. APSF Highlights 12 Perioperative Patient Safety Priorities. APSF Newsletter 2018; 33: 33.

- Greenberg S. Opioid-Induced Ventilatory Impairment: An Ongoing APSF Initiative. APSF Newsletter 2018; 32: 57-88.

- Miyasaka K. A Japanese Perspective on Patient Safety. APSF Newsletter 2016; 31: 18-19.

- Takazawa T, Miayasaka K, Sawa T, Iida H. Current Status of Sugammadex Usage and the Occurrence of Sugammadex-Induced Anaphylaxis in Japan. APSF Newsletter 2018; 33: 1.

- Sasakawa T, Miyasaka K, Sawa T, Iida H. Postoperative Recurarization After Sugammadex Administration due to Lack of Neuromuscular Monitoring: The Japanese Experience. APSF Newsletter 2020; 35: 42-43.

- Zucco L, Levy N, Ketchandji D, Aziz M, Ramachandran SK. An Update on the Perioperative Considerations for COVID-19 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). APSF Newsletter 2020; 35: 33, 35-39.

- Warner MA, Stoelting RK. Our Founders and Their Gift of Core Principles. APSF Newsletter 2020; 35; 79-80.

- Urman RD, Posner KL, Howard SK, Warner MA. 2017 Marks 30 Years of APSF Research Grants. APSF Newsletter 2018; 32: 57, 61-62.

- Delson N, Sloan C, McGee et al. Parametrically adjustable intubation mannequin with real time visual feedback. Simul Healthc 2012; 7: 183-191.

| Read more articles from this special collection hosted by the APSF on Pulse Oximetry and the Legacy of Dr. Takuo Aoyagi. |

Articles

Articles