The intraoperative environment is a complex workplace, where the quality of patient care depends on effective teamwork and communication. Though often deferred to the surgical team, chest tube management should be a shared responsibility. For surgeries in which chest tube thoracostomy is required for postoperative care, confirming placement, functionality, and application of suction is critical. Early recognition and response to the decompensating post-thoracic surgical patient, via heightened vigilance and careful closed-loop-communication among all operating room staff members, not only promotes an intraoperative culture of safety but may also be life-saving.

A case report of intraoperative tension pneumothorax and review of chest tube management

Introduction

A tension pneumothorax (TPT) occurs when air accumulates in the intrapleural cavity, leading to lung collapse, pulmonary arterial shunting, hypoxemia, and hemodynamic collapse.1 This case illustrates the importance of teamwork and communication, focusing on chest tube management, to promptly detect and treat a TPT.

Clinical presentation

A 60-year-old woman with active smoking, hypertension, AIDS, and hepatitis C presented with recurrent pneumonia with a loculated exudative pleural effusion. She underwent thoracentesis, pleural biopsy, chemical pleurodesis, and decortication via left thoracoscopy, complicated by parenchymal bleeding which required conversion to thoracotomy. While mechanically ventilated during repositioning from lateral to supine, sudden difficulties in ventilation and oxygenation were noted. High peak airway pressures, hypoxemia, tachycardia, and refractory hypotension developed, and physical exam revealed expanding subcutaneous emphysema with loss of left-sided lung sounds. In addition to hemodynamic management, a survey of all equipment identified suction disconnected from the chest tube apparatus. Application of suction and removal of occlusive thrombi via flushing resulted in rapid hemodynamic and respiratory improvements. Intraoperative chest x-ray confirmed proper chest tube positioning and revealed resolution of TPT (Figure 1).

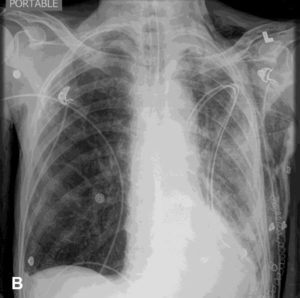

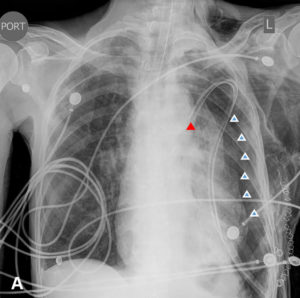

Figure 1: Serial post-operative chest x-rays, demonstrating a tension pneumothorax and its resolution.

A. Immediate post-operative AP view. Endotracheal tube in place, with tip above the carina. Left chest tube with suction applied, with tip properly projecting over the medial aspect of the left upper lung (red arrow). Moderate-sized left pneumothorax (white arrows) with some mass effect and mild shift to the right side; extensive subcutaneous emphysema present.

Discussion

Despite recent formalization of patient safety with mandated briefings and time-outs, the end of surgery is still a somewhat dysregulated time when mishaps can easily occur. Since the surgical team often manages the thoracostomy, an anesthesia provider may assume the chest tube is properly placed, functional, and has appropriate suction applied while preparing for emergence. When that assumption is erroneous, life-threatening consequences may occur, as in the presented case.

Anesthesia providers should maintain a working knowledge of chest tube management and its complications.2 This knowledge empowers the anesthesia professional to take ownership, recognize malfunctioning of the drainage apparatus, and ensure effective closed-loop-communication among all operating room team members.

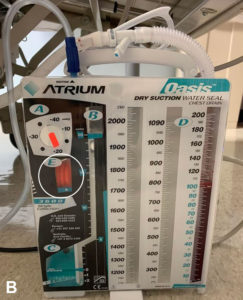

Chest tube thoracostomy is a routine procedure that drains fluid, blood or air from the pleural space, allowing lung re-expansion.3 Chest tubes are connected to chest drainage systems via a three-way chamber. Gravity or suction restores negative pressure to the pleural space by acting as a one-way valve to facilitate lung expansion. The collection chamber collects fluid drainage, while in the water seal chamber, a column of water prevents air from being drawn back into the pleural space during inhalation. A suction chamber may be connected to either wall suction or placed on a water seal (Figure 2).3 Whenever chest thoracostomy is used, the tubing should be inspected for kinks, clamps, internal blockages (e.g. clot, debris), and misplacement to ensure functionality (Table 1).2

Figure 2: Example of chest tube apparatus used in the operating room.

A. An example of a chest tube apparatus commonly used in the operating room. Section A denotes dry suction control, preset at -20mm H2O, yet can be adjusted to any setting between -10 and -40mm H2O. Section B denotes the water seal chamber. Section C is a water seal monitor, where air bubbles are created in the presence of an air leak. Section D is a collection chamber, into which the fluid from the patient is collected and measured. Section E is an expandable orange bellows that is deflated in the absence of suction.

Table 1: Chest tube management safety checklist.

| Chest Tube Apparatus |

|

|

| Chest Tube Tubing |

|

|

In mechanically ventilated patients, high pressures and air trapping place patients at high risk of TPT if the thoracostomy is not functioning. Therefore, the chest tube unit should be placed to suction upon chest closure to facilitate lung re-expansion, as development of post-operative pneumothorax is less likely when suction is applied.4 Presence of fluid oscillations in the water seal chamber (known as “tidaling”) is a direct reflection of the degree of lung re-expansion, such that tidaling decreases as the lung re-expands. Prior to emergence, an anesthesia provider’s verbal confirmation regarding application of suction as well as visual confirmation via tidaling are recommended. Importantly, multidisciplinary communication, shared responsibility, and heightened vigilance is required by all members of the operating room to ensure proper chest tube management and prevent life-threatening complications.

Ashley V. Wells, M.D.

Department of Anesthesiology, Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System, New York, NY 10010

Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Care and Pain Medicine, New York University Langone Health Medical Center, New York, NY 10016

Andrea Luncheon-Hilliman, M.D.

Department of Anesthesiology, Elmhurst Hospital Center, Elmhurst, NY 11373

Department of Critical Care Medicine, Elmhurst Hospital Center, Elmhurst, NY 11373

Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY 10029

Sabrina D. Bhagwan, M.D.

Department of Anesthesiology, Elmhurst Hospital Center, Elmhurst, NY 11373

Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY 10029

Department of Pediatrics, The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY 10029

Elvera L. Baron, M.D., Ph.D.

Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY 10029

Department of Medical Education, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York NY 10029

Drs. Wells, Luncheon-Hilliman, Bhagwan, and Baron report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Roberts DJ, Leigh-Smith S, Faris PD, et al. Clinical presentation of patients with tension pneumothorax: a systematic review. Ann Surg., 2015; 261: 1068-1078.

- Bacon AK, Paix AD, Williamson JA, Webb RK, Chapman MJ. Crisis management during anaesthesia: pneumothorax. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14: e18.

- Porcel JM. Chest tube drainage of the pleural space: a concise review for pulmonologists. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2018; 81: 106-115.

- Lang P, Manickavasagar M, Burdett C, Treasure T, Fiorentino F. Suction on chest drains following lung resection: evidence and practice are not aligned. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016; 49: 611-616.

Articles

Articles